Preface

THIS volume contains the substance of a course of popular Lectures delivered at Cardiff in 1901. The work does not claim in any way to be an original contribution to knowledge, and is published on the recommendation of some friends in whose literary judgment I have confidence. In a popular book of this kind I have not thought it necessary to give detailed references to authorities, but a list of a few of the books which I used in the preparation of the Lectures, and which are likely to be interesting to readers of Welsh history, may be useful. Among mediæval works I may mention the two Welsh chronicles—the Annales Cambriæ and the Brut y Tywysogion, both published in the Rolls Series; Geoffrey of Monmouth’s “History of the Kings of Britain” (translated in Bohn’s “Six Old English Chronicles”); Giraldus Cambrensis, “The Itinerary and Description of Wales” (translated in Bohn’s library); the prefaces, especially those by Brewer, in the Rolls Series edition of Giraldus, will be found interesting. Of the English chroniclers, Ordericus Vitalis, Roger of Wendover, and Matthew Paris are perhaps the most valuable for the history of Wales and the Marches during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Among modern books, the reader may be referred to Rhys and Jones, “The Welsh People”; Freeman, “William Rufus”; Thomas Stephens, “Literature of the Kymry”; Henry Owen, “Gerald the Welshman”; Clark, “Mediæval Military Architecture,” and “The Land of Morgan”; Newell, “History of the Welsh Church”; Tout, “Edward I.”; and the “Dictionary of National Biography.” Since these Lectures were delivered at least three books on Welsh history have appeared which deserve mention: Mr. Bradley’s “Owen Glyndwr,” with a summary of earlier Welsh history; Mr. Owen Edwards’s charmingly written volume in the Story of the Nations Series; and Mr. Morris’s valuable work on “The Welsh Wars of Edward I.”

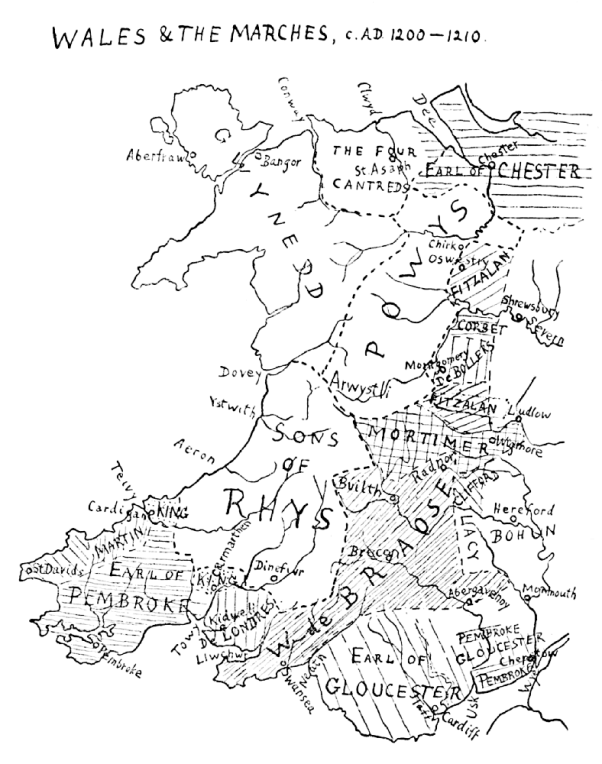

The maps are taken from large wall maps which I used when lecturing. In drawing up the map of Wales and the Marches at the beginning of the thirteenth century, I had the assistance of my friend and former pupil, Mr. Morgan Jones, M.A., of Ferndale, who generously placed at my disposal the results of his researches into the history of the Welsh Marches.

1. Introductory

IN the following lectures no attempt will be made to give a systematic account of a political development, which is the ordinary theme of history. History is “past politics” in the wide sense of the word. It has to do with the growth and decay of states and institutions, and their relations to each other. The history of Wales in the Middle Ages, viewed from the political standpoint, is a failure; its interest is negative; and in this introductory lecture I intend to discuss “the failure of the nation” (to use the words of Professor Rhys and Mr. Brynmor Jones) “to effect any stable and lasting political combination.” Wales failed to produce or develope political institutions of an enduring character—failed to become a state. Its history does not possess the unity nor the kind of interest which the history of England possesses, and which makes the study of English history so peculiarly instructive to the student of politics. In English history we study primarily the growth of the principle of Representative Government, which we can trace for centuries through a long series of authoritative records. That is the great gift of England to the world. Not only has Wales entered on this inheritance; it helped to create it. It was Llywelyn ap Iorwerth who began the revolt against John which led to the Great Charter, and the clauses of the Great Charter itself show that it was the joint work of English and Welsh. Wales again exerted a decisive influence on the Barons’ War—the troubles in which the House of Commons first emerged. And Wales—half of it for more than six hundred years—half of it for nearly four hundred—has lived under the public law and administrative system which the Norman and Angevin kings of England built up on Anglo-Saxon foundations. This public law and this administrative system have become part and parcel of the life and history of Wales. The constitutional history of England is one of the elements which go to make up the complex history of Wales.

The history of Wales, taken by itself, is constitutionally weak; and its interest is social or personal, archæological, artistic, literary—anything but political. And the fact—which is indisputable—that Wales failed to establish any permanent or united political system needs explanation.

The ultimate explanation will perhaps be found in the geography of the country. The mountains have done much to preserve the independence and the language of Wales, but they have kept her people disunited; and the Welsh needed a long drilling under institutions, which could only grow up in a land less divided by nature, before they could develope their political genius.

Wales, owing largely to its geography, had the misfortune never to be conquered at one fell swoop by an alien race of conquerors. Such a conquest may not at first sight strike one as a blessing, but it is, if it takes place when a people is in an early, fluid, and impressionable stage, as may be seen from a comparison of countries which have undergone it with countries which have not—a comparison, for instance, of England with Ireland or Germany. Perhaps the nearest parallel in the history of Wales to the Norman Conquest of England is the conquest of Wales by Cunedda, the founder of the Cymric kingdom, in the dark and troublous times which followed the withdrawal of the Roman troops from Britain. But though an invader and a conqueror, Cunedda was not an alien; he spoke the same language as the people he conquered and belonged to the same race to which the most important part of them belonged. And this militated against his chances of becoming a founder of Welsh unity. A race of conquerors distinct from the conquered in blood and language and civilisation, must hold together for a time; they form an official governing class, enforcing the same principles of government, and establishing a uniform administration throughout the country. And the uniform pressure reacts on the conquered, turning them from a loose group of tribes into a nation. This is what the Norman Conquest did for England. But if the conquerors are of the same race and language as the conquered, they readily mix with them; instead of holding together they identify themselves with local jealousies and tribal aspirations. This happened again and again in Germany. A Saxon emperor sends a Saxon to govern Bavaria as its duke and hold it loyal to the central government; the Saxon duke almost instantaneously becomes a Bavarian—the champion of tribal independence against the central government; and so the Germans remained a loose group of tribes and states—a divided people. This illustration suggests one of the reasons why Cunedda’s conquest failed to unite Wales.

Again the custom of sharing landed property among all the sons tended to prevent the growth of Welsh unity. Socially it appears far more just and reasonable than the custom of primogeniture. It is with the growth of feudalism (already apparent in the Welsh laws of the tenth century) that its political dangers become evident. The essence of feudalism is the confusion of political power and landed property; the ruler is lord of the land, the landlord is the ruler. If landed property is divided, political power is divided. When the Lord Rhys died in 1197 leaving four sons, Deheubarth had four rulers and formed four states instead of one; and civil war ensued.

The unity of Welsh history is not to be found in the growth of a state or a political system. But may we regard the history of Wales as a long and heroic struggle inspired by the idea of nationality? A caution is necessary here. It is one of the besetting sins of historians to read the ideas of the present into the past; and to the general public historical study is dull unless they can do so. It is very difficult to avoid doing so; it needs a severe training, a long immersion in the past, and a steady passion for truth above all things. In no case perhaps is this warning so necessary as in matters involving the idea of nationality. This is characteristic of the present age, but it has not been characteristic of any other to anything like the same extent. We live in an atmosphere of nationality; we have seen it create the German Empire and the kingdom of Italy, and the Welsh University; we see it now labouring to break up the Austrian Empire, and perhaps changing the unchanging East. But the whole history of Europe shows that it is an idea of slow and comparatively late growth. The first appearance of nationality as a conscious principle of political action is found in England—and possibly in France—at the beginning of the thirteenth century, and in Wales about the same time; in the other countries of Europe much later. And it was very rarely till the very end of the eighteenth century that it became a dominant factor in politics. Of course our ancestors always hated a foreigner—but they did not love their fellow-countrymen. The one thing a man hated more than being driven out of house and home by a foreign invader, was being driven out by his next-door neighbour; and, as his neighbour was more likely to do it, and when he did it, to stay, he hated his neighbour most. A certain degree of order and settled government was necessary before the national idea could become effective.

In mediæval Wales it never succeeded in uniting the people; the petty patriotism of the family stood in the way of the larger patriotism of the nation; local rivalries and jealousies were always stronger than the sense of national unity. The attempt of Llywelyn ap Iorwerth to create a National Council, like the Great Council of England, died with him. In the final struggle with Edward I., when for a few months the idea of Welsh unity was nearest realisation in action, the men of Glamorgan fought on the winning side. Read the “Brut y Tywysogion” and consider how far the actions there related can have been inspired by the feeling of nationality. Here is the account in the “Brut” of what was happening in Wales in 1200 and the following years, the period represented by our map.

“1200. One thousand and two hundred was the year of Christ when Gruffudd, son of Cynan, son of Owain, died, after taking upon him the religious habit, at Aberconway,—the man who was known by all in the isle of Britain for the extent of his gifts, and his kindness and goodness; and no wonder, for as long as the men who are now shall live, they will remember his renown, and his praise and his deeds. In that year, Maelgwn, son of Rhys, sold Aberteivi, the key of all Wales, for a trifling value, to the English, for fear of and out of hatred to his brother Gruffudd. The same year, Madog, son of Gruffudd Maelor, founded the monastery of Llanegwestl, near the old cross, in Yale.

“1201. The ensuing year, Llywelyn, son of Iorwerth, subdued the cantrev of Lleyn, having expelled Maredudd, son of Cynan, on account of his treachery. That year on the eve of Whitsunday, the monks of Strata Florida came to the new church; which had been erected of splendid workmanship. A little while afterwards, about the feast of St. Peter and St. Paul, Maredudd, son of Rhys, an extremely courteous young man, the terror of his enemies, the love of his friends, being like a lightning of fire between armed hosts, the hope of the South Wales men, the dread of England, the honour of the cities, and the ornament of the world, was slain at Carnwyllon; and Gruffudd, his brother, took possession of his castle at Llanymddyvri. And the cantrev, in which it was situated, was taken possession of by Gruffudd, his brother. And immediately afterwards, on the feast of St. James the Apostle, Gruffudd, son of Rhys, died at Strata Florida, having taken upon him the religious habit; and there he was buried. That year there was an earthquake at Jerusalem.

“1202. The ensuing year, Maredudd, son of Cynan, was expelled from Meirionydd, by Howel, son of Gruffudd, his nephew, son of his brother, and was despoiled of everything but his horse. That year the eighth day after the feast of St. Peter and St. Paul, the Welsh fought against the castle of Gwerthrynion, which was the property of Roger Mortimer, and compelled the garrison to deliver up the castle, before the end of a fortnight, and they burned it to the ground. That year about the first feast of St. Mary in the autumn, Llywelyn, son of Iorwerth, raised an army from Powys, to bring Gwenwynwyn under his subjection, and to possess the country. For though Gwenwynwyn was near to him as to kindred, he was a foe to him as to deeds. And on his march he called to him all the other princes, who were related to him, to combine in making war together against Gwenwynwyn. And when Elise, son of Madog, son of Maredudd, became acquainted therewith, he refused to combine in the presence of all; and with all his energy he endeavoured to bring about a peace with Gwenwynwyn. And therefore, after the clergy and the religious had concluded a peace between Gwenwynwyn and Llywelyn, the territory of Elise, son of Madog, his uncle, was taken from him. And ultimately there was given him for maintenance, in charity, the castle of Crogen, with seven small townships. And thus, after conquering the castle of Bala, Llywelyn returned back happily. That year about the feast of St. Michael, the family of young Rhys, son of Gruffudd, son of the lord Rhys, obtained possession of the castle of Llanymddyvri.”

One may almost say that Wales is Wales to-day in spite of her political history. Wales owes far more to her poets and men of letters than to her princes and their politics.

Giraldus Cambrensis laid his finger on the spot, when he said: “Happy would Wales be if it had one prince, and that a good one.” A necessary preliminary to the union of Welshmen was the wiping out of all independent Welsh princes except one. Till that happened local feeling would always remain stronger than national feeling; the disintegrating forces of family feuds and personal ambitions and clannish loyalty would always outweigh the sense of national unity.

The Lords of the Marches were slowly doing this for Wales; they were wiping out all the independent Welsh princes except one. We may see the process going on in the accompanying map, which gives the chief political divisions of Wales at the beginning of the thirteenth century, and we will turn for a few minutes to consider the fortunes of some of these petty states and the manner of the men who ruled them.

The great Palatine Earldom of Chester, a kingdom within the kingdom, was ruled before 1100 by Hugh the Wolf, of Avranches, who conquered for a time the north coast of Wales. In Anglesey he built a castle, and kennelled the hounds he loved so well in a church, to find them all mad the next morning. The stories of his savage mutilation of his Welsh prisoners show that he merited the name of “the Wolf.” Yet he was the friend of the holy Anselm, and died a monk. The struggle between Chester and Gwynedd for the possession of the Four Cantreds, the lands between the Conway and the Dee, was almost perpetual during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, and the fortune of war continually changing. With the extinction of the old line of the Earls of Chester (1237) and the grant of the earldom to Prince Edward (1254), a new era opened for Wales.

Further south, in the Middle March, along the upper valleys of the Severn and the Wye, the great power of the Mortimers was growing. They had already stretched out a long arm to grasp Gwerthrynion. But the greatest expansion of their power came later, under Roger Mortimer, grandson of Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, friend of Edward I. in the wild days of his youth, persistent foe of Llywelyn ap Gruffydd; and soon the Mortimer lands embraced all Mid-Wales and reached the sea, and a Mortimer was strong enough to depose and murder a king and rule England as paramour of the queen. Savage as the Mortimers were, they were mild compared with one of their predecessors. Robert Count of Bellesme and Ponthieu, the great castle builder of his time, became Earl of Shrewsbury and Arundel in 1098. Men had heard tales of his ferocity on the Continent—how he starved his prisoners to death rather than hold them to ransom; how, when besieging a castle, he threw in the horses to fill up the moat, and when these were not enough he gave orders to seize the villeins and throw them in, that his battering rams might go forward on a writhing mass of living human bodies. These tales seemed incredible in England, but the men of the Middle March believed them when they were “flayed alive by the iron claws” of the devil of Bellesme. In his rebellion against Henry I. the princes of Gwynedd supported him, till their army was bought over by the lying promises of the king; but the day when the Earl of Shrewsbury surrendered to King Henry and the whole force of England was a day of deliverance alike to England and to Wales.

We next come to the group of lordships held about this time by William de Braose, lord of Bramber in Sussex. They stretched from Radnor to Gower, from the Monnow to the Llwchwr, and included the castles of Builth, Brecon, Abergavenny. But he held these lands by different titles, and they were never welded together. William de Braose began his public career by calling the princes of Gwent to a conference at Abergavenny, and massacring them. He was on intimate terms with King John, who gave Prince Arthur into his keeping; but this was a piece of work which even De Braose recoiled from, and he refused to burden his soul with Arthur’s murder. A few years later John suddenly turned against him, and demanded his sons as hostages. His wife, Maud de St. Valérie, who lived long in the popular memory as a witch, sent back the answer: she would not entrust her children to a man who had murdered his nephew. The king chased Braose from his lands, caught his wife and eldest son, and starved them to death in Windsor Castle. The Braose family continued to hold Gower, but the rest of their possessions passed to other houses—Brecon to the Bohuns of Hereford, Elvael to Mortimer, Abergavenny to Hastings, Builth first to Mortimer and then to the Crown.

Glamorgan, during our period, was attached to the earldom of Gloucester. From Fitzhamon the Conqueror it passed, through his daughter, to Robert of Gloucester, and early in the thirteenth century to the great house of Clare, Earls of Gloucester and Hertford, who held the balance between parties in the Barons’ War. With the organisation of Glamorgan and with its great rulers we shall deal later. At the time represented by our map, it was in the hands of King John, who obtained it by marriage. John divorced his wife in 1200, but managed to keep her inheritance till nearly the end of his reign; and Fawkes de Bréauté, the most infamous of his mercenary captains, lorded it in Cardiff Castle.

Further west, between the Llwchwr and the Towy, lay the lordship of Kidweli, held by the De Londres family, who had accompanied Fitzhamon in the conquest of Glamorgan, and were lords of Ogmore and founders of Ewenny. One episode in the history of this family may be mentioned—the battle in the Vale of Towy in 1136, when Gwenllian, the heroic wife of Rhys ap Gruffydd, led her husband’s forces against Maurice and De Londres, and was defeated and slain by the Lord of Kidweli. Her death was soon avenged by the slaughter of the Normans at Cardigan. The present castle of Kidweli dates from the later thirteenth century, before the war of 1277, after the lordship had passed to the Chaworths.

In the extreme west, in Dyfed, the land of fiords, Arnulf of Montgomery had early founded the Norman power, but he was involved in the fall of his brother, Robert of Bellesme, and Henry I. tried to form the land into an English shire, and planted a colony of Flemings in “Little England beyond Wales.” But it was too far off for the royal power to be effectively exercised there, and the Earldom of Pembroke was granted to a branch of the De Clares, who had already conquered Ceredigion, and built castles at Cardigan and Aberystwyth. The De Clares also held Chepstow and lands in Lower Gwent. The Earldom itself was smaller than the present shire of Pembroke, and William Marshall, who succeeded the De Clares through his marriage with the daughter of Richard Strongbow (1189), owed his commanding position in English history of the thirteenth century far more to his personal qualities, his courage and wisdom and patriotism, than to his territorial possessions.

It was by driving the De Clares out of Ceredigion in Stephen’s reign that Rhys ap Gruffydd laid the foundation of his power, and raised Deheubarth to be the foremost of the native principalities. The Lord Rhys was clever and farseeing enough to win the confidence of Henry II., and received from him the title of Justiciar—or King’s Deputy—in South Wales. As long as Owain Gwynedd lived the unusual spectacle was seen of a prince of South Wales and a prince of North Wales working harmoniously together. But after Owain’s death (1170) Rhys fought with his successors over the possession of Merioneth, while Owain Cyfeiliog, the poet-prince of Powys, did all he could to thwart him. In 1197 the death of Rhys, “the head and the shield and the strength of the South and of all Wales,” and the civil wars among his sons, opened his principality again to the encroachment of foes on all sides, and removed one danger from Powys. Powys, however, was being steadily squeezed by the pressure of Gwynedd on one side, and the growing power of Mortimer on the other, and its princes resorted to a shifty diplomacy and a general adherence—open or secret as circumstances dictated—to the English Crown, till they sank at length into the position of petty feudatories of the English king.

The Prince of Gwynedd alone upheld the standard of Welsh nationality, the dragon of Welsh independence; only in Gwynedd and its dependencies did the Welsh public law prevail over feudal custom. And what was the result? Exactly what Giraldus Cambrensis had foreseen and longed for. The eyes of Welshmen everywhere began to turn to the Lord of Eryri, the one hope of Wales. It was an alluring—an inspiring prospect, which opened before the princes of Gwynedd—to head a national movement, drive out the foreigners, and unite all Wales under their sway. Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, at the end of his long reign, deliberately rejected the dream. That is the meaning of his emphatic declaration of fidelity and submission to Henry III. in 1237. “Llywelyn, Prince of Wales, by special messengers sent word to the king that, as his time of life required that he should thenceforth abandon all strife and tumult of war, and should for the future enjoy peace, he had determined to place himself and his possessions under the authority and protection of him, the English king, and would hold his lands from him in all fealty and friendship, and enter into an indissoluble treaty; and if the king should go on any expedition he would, to the best of his power, as his liege subject, promote it, by assisting him with troops, arms, horses, and money.” Llywelyn the Great refused to dispute the suzerainty of England. This may appear pusillanimous to the enthusiastic patriot, but subsequent events proved the old statesman’s wisdom and clearsightedness. His successors were less cautious, were carried away by the patriotism round them and the syren voices of the bards. And to Llywelyn ap Gruffydd the prospect was even more tempting than to Llywelyn ap Iorwerth. The Barons’ War weakened the power of England, and the necessities of Simon de Montfort led him to enter into an alliance with Llywelyn. The expansion of Gwynedd was great and rapid. Llywelyn’s rule extended as far south as Merthyr, and made itself felt on the shores of Carmarthen Bay. The Earl of Gloucester found it necessary to build Caerphilly Castle to uphold his influence in Glamorgan. But it was just the expansion of Llywelyn’s power which forced Edward I. to overthrow him once for all. “We hold it better”—so ran Edward’s proclamation in 1282—“that, for the common weal, we and the inhabitants of our land should be wearied by labours and expenses this once, although the burden seem heavy, in order to destroy their wickedness altogether, than that we should in future times, as so often in the past, be tormented by rebellions of this kind at their good pleasure.”

The “Principality” now became shire land—under English laws and English administration. The rest of Wales remained divided up into Marcher Lordships for another two hundred and fifty years, under feudal laws—a continual source of disturbance and scene of disorder. These were the lands in which the King’s Writ did not run, where (to summarise the description in the Statute of 1536) “murders and house-burnings, robberies and riots are committed with impunity, and felons are received, and escape from justice by going from one lordship to another.”

Yet the Marcher Lords did something for Welsh civilisation in their earlier centuries. Guided by enlightened self-interest, they often founded towns, granting considerable privileges to them in order to attract burgesses—such as low rents, and freedom from arbitrary fines. Fairs, too, were established and protected by the Lords Marchers. The early lords of Glamorgan seem to have been specially successful in this respect; in the twelfth century immigrants from other parts of Wales are said to have come to reside in Glamorgan, owing to the privileges and comparative security which were to be found there. Nor perhaps has it been sufficiently recognised how soon the Lords of the Marches began drilling their Welsh subjects in Anglo-Norman methods of local self-government. Most of the greater Marcher Lords possessed estates in England; not a few of them, such as William de Braose, served as sheriffs in English shires; some, such as John de Hastings, were judges in the royal courts. They introduced into Wales methods of government which they learnt in England, and institutions with a great future before them, like the Franco-Roman “inquest by sworn recognitors,” from which trial by jury was developed, were soon acclimatised in the Marches of Wales.

2. Geoffrey Of Monmouth

WHEN Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote, Norman influence in Wales was at its height. In the old days we used to begin English history with William the Conqueror; since Freeman wrote his five thick volumes and proved—not that the Norman Conquest was unimportant—but that it did not involve a breach of continuity, a new start in national life, the pendulum has swung too much the other way, and the tendency of late years has been to underestimate the importance of the Norman Conquest.

The Norman wherever he went brought little that was new; he was but a Norseman—a Viking—with a French polish. He had no law of his own; he had forgotten his own language, he had no literature. But he had the old Norse energy; which not only drove him or his ancestors to settle and conquer in lands so distant and diverse as Russia and Sicily, Syria and North America, but enabled him to infuse new life into the countries he conquered. Further, he still retained that adaptability and power of assimilation which is characteristic of peoples in a primitive stage of civilisation. With a wonderful instinct he fastened on to the most characteristic and strongest features of the different nations he was brought in contact with, developed them, gave them permanent form, and often a world-wide importance.

The Norman conquerors were not always fortunate in their selection. Ireland has little to thank them for. The most striking characteristic which they found in Ireland was anarchy, and they brought it to a high pitch of perfection. To quote Sir J. Davies’s luminous discourse on Ireland, in 1612: “Finding the Irish exactions to be more profitable than the English rents and services, and loving the Irish tyranny which was tied to no rules of law and honour better than a just and lawful seigniory, they did reject the English law and government, received the Irish laws and customs, took Irish surnames, as MacWilliam, MacFeris, refused to come to Parliaments, and scorned to obey those English knights who were sent to command and govern this kingdom.”

One extortionate Irish custom, called “coigny,” they specially affected, of which it was said “that though it were first invented in hell, yet if it had been used and practised there as it hath been in Ireland, it had long since destroyed the very kingdom of Beelzebub.”

England and Wales were more fortunate. In England—while the old English literature was crushed out by the heel of the oppressor, the Norman instinct seized on the latent possibilities of the old English political institutions, welded them into a great system, developed out of them representative government, and created a united nation.

In Wales, the Normans paid little or no heed to Welsh laws and political institutions; the law of the Marches was the feudal law of France, the charters of liberties of the towns were imported from Normandy; the Welsh Marches and border shires were the most thoroughly Normanised part of the whole kingdom. But with a fine instinct for the really great things, in Wales the Normans seized on the literary side—the poetic traditions of the people—giving them permanent form, adding to them, making them for ever part of the intellectual heritage of the whole world.

It may very likely be a mere accident that the earliest Welsh manuscripts date from the twelfth-century—Norman times; it may also imply an increased literary productiveness. It may be due to accidental causes that the first accounts of Eisteddfodau extant date from the twelfth century; it may also be that the institution excited new interest, received new attention and honour, under the influence of the open-minded and keen-sighted invaders. Take, for instance, the account of the great Eisteddfod in 1176, from the Brut y Tywysogion: “The lord Rhys held a grand festival at the castle of Aberteivi, wherein he appointed two sorts of competitions—one between the bards and poets, and the other between harpers, fiddlers, pipers, and various performers of instrumental music; and he assigned two chairs for the victors in the competitions; and these he enriched with vast gifts. A young man of his own court, son to Cibon the fiddler, obtained the victory in instrumental music, and the men of Gwynedd obtained the victory in vocal song; and all the other minstrels obtained from the lord Rhys as much as they asked for, so that there was no one excluded.” An Eisteddfod where every one obtained prizes, and every one was satisfied, suggests the enthusiasm natural to a new revival. It was now—when Wales was brought in contact with the great world through the Normans—that modern Welsh poetry had its beginning. The new intellectual impetus is clearly illustrated by the change which takes place in the Welsh chronicles about 1100. Before that time they are generally thin and dreary: they suddenly become full, lively, and romantic. Wales was not exceptional in this renaissance; something of the same sort occurred in most parts of Europe; and the renaissance is no doubt to be connected with the Crusade, the reform of the Church, in a word, with the Hildebrandine movement, and so ultimately with the Burgundian monastery of Clugny. But it was the Normans who brought this new life to England and Wales; the Normans were the hands and feet of the great Hildebrandine movement of which the Clugniac popes were the head.

Among the Norman magnates who encouraged the intellectual movement in Wales—one stands out pre-eminent—Robert Earl of Gloucester and Lord of Glamorgan, a splendid combination of statesman, soldier, patron of letters. Robert was a natural son of Henry I.—born before 1100—there is no evidence that his mother was the beautiful and famous Nest, daughter of Rhys ap Tudor. He acquired the Lordship of Glamorgan together with the Honour of Gloucester and other lands in England and Normandy, by marriage with Mabel, daughter and heiress of Fitzhamon, conqueror of Glamorgan. An account of the wooing is preserved in old rhymed chronicle: the king conducts negotiations; the lady remarks that it was not herself but her possessions he was after—and she would prefer to marry a man who had a surname. The account is not historical, as surnames had not come in: in the early twelfth century the lady would have expressed her meaning differently. However, there is evidence that she was a good wife: William of Malmesbury says, “She was a noble and excellent woman, devoted to her husband, and blest with a numerous and beautiful family.” Robert was a great builder of castles; Bristol and Cardiff Castles were his work, and many others in Glamorgan; he organised Glamorgan, giving it the constitution of an English shire—with Cardiff Castle as centre and meeting-place. After Henry I.’s death, he was the most important man in England, and was the only prominent man who played an honourable part in the civil wars which are known as the reign of Stephen; he died in 1147. His relations with the Welsh appear to have been good; large bodies of Welsh troops fought under him at the battle of Lincoln, 1141—he was probably the first Norman lord of Glamorgan who could thus rely on their loyalty. And it is significant that in the earliest inquisitions extant for Glamorgan—or inquests by sworn recognitors—Welshmen were freely employed in the work of local government.

Robert of Gloucester was a magnificent patron of letters; to his age Giraldus Cambrensis looked back with longing regret as to the good old times in which learning was recognised and received its due reward. To Robert of Gloucester, William of Malmesbury, the greatest historian of the time, dedicated his history, attributing to him the magnanimity of his grandfather the Conqueror, the generosity of his uncle, the wisdom of his father, Henry I. He was the founder of Margam Abbey, whose chronicle is one of the authorities for Welsh history; Tewkesbury, another abbey whose chronicle is preserved, counted him among its chief benefactors; Robert de Monte, Abbot of Mont St. Michel, the Breton and lover of Breton legends, was a native of his Norman estates at Torigny, and wrote a valuable history of his times. Among the brilliant circle of men of letters who frequented his court at Gloucester and Bristol and Cardiff were Caradoc of Llancarven, whose chronicle (if he ever wrote one) has been lost, and greatest of all Geoffrey of Monmouth.

Geoffrey dedicated his History of the Kings of Britain to Robert: “To you, therefore, Robert Earl of Gloucester, this work humbly sues for the favour of being so corrected by your advice that it may be considered not the poor offspring of Geoffrey of Monmouth, but, when polished by your refined wit and judgment, the production of him who had Henry, the glorious King of England, for his father, and whom we see an accomplished scholar and philosopher, as well as a brave soldier and tried commander.”

Not very much is known about Geoffrey. The so-called “Gwentian Brut,” attributed to Caradoc of Llancarven, on which his biographers have relied for a few details of his life, is very untrustworthy, and, according to the late Mr. Thomas Stephens, was written about the middle of the sixteenth century, though containing earlier matter. The sixteenth century was a great age for historical forgeries. We find a Franciscan interpolating passages in a Greek manuscript of the New Testament in order to refute Erasmus; a learned Oxonian forging a passage in the manuscript of Asser’s “Life of Alfred” to prove that Alfred founded the University of Oxford; and Welsh genealogies invented by the dozen and the yard—reaching back to “son of Adam, son of God.” The “Gwentian Brut” or “Book of Aberpergwm” is in doubtful company. The following seem to be the facts known about Geoffrey. In 1129 he was at Oxford, in company with Walter, Archdeacon of Oxford (not Walter Mapes). His father’s name was Arthur; and he was connected with the Welsh lords of Caerleon. He calls himself “of Monmouth,” either as being born there, or as having a connection with the Benedictine monastery at Monmouth, which was founded by a Breton, and kept up connections with Brittany and Anjou. He may have been archdeacon—but not of Monmouth. The first version of his history was finished in or before April, 1139, and the final edition of the History was completed by 1147. In his later years he resided at Llandaff. He was ordained priest in February, 1152, and consecrated bishop of St. Asaph in the same month. In 1153 he was one of the witnesses to the compact between King Stephen and Henry of Anjou, which ended the civil wars. He died at Llandaff in 1153.

We will now turn to consider the sources of his History of the Kings of Britain. Geoffrey says: “In the course of many and various studies I happened to light on the history of the Kings of Britain, and wondered that, in the account which Gildas and Bede, in their elegant treatises, had given of them, I found nothing said of those kings who lived here before Christ, nor of Arthur, and many others; though their actions were celebrated by many people in a pleasant manner, and by heart, as if they had been written. Whilst I was thinking of these things, Walter, Archdeacon of Oxford, a man learned in foreign histories, offered me a very ancient book in the Britannic tongue, which, in a continued regular story and elegant style, related the actions of them all, from Brutus down to Cadwallader. At his request, therefore, I undertook the translation of that book into Latin.” At the end of his history he adds: “I leave the history of the later kings of Wales to Caradoc of Llancarven, my contemporary, as I do also the kings of the Saxons to William of Malmesbury and Henry of Huntingdon. But I advise them to be silent concerning the kings of the Britons, since they have not that book written in the Britannic tongue, which Walter, Archdeacon of Oxford, brought out of Britannia.”

There has been a good deal of controversy as to whether this very ancient book was in Welsh or Breton, but the first question is, Did it ever exist? Was Geoffrey a translator, or an inventor, or a collector of oral traditions current in Wales or Brittany during his time?

There can be little doubt that the conclusion of Thomas Stephens, in the “Literature of the Kymry,” is correct—that “Geoffrey was less a translator than an original author.” It is very doubtful whether the Britannic book ever existed, whether it was not a mere ruse, such as was often resorted to by mediæval romancers, and is still a favourite method with modern historical novelists—to give their works an appearance of genuineness. It has been argued against this, that in that case, Archdeacon Walter must have been a party to the fraud—which is incredible. Such an argument implies a large ignorance of the archdeacons of the twelfth century—when it was a question solemnly discussed among the learned—whether an archdeacon could possibly be saved. It would be well if there were nothing worse to bring against them than such an innocent fraud on the public as this. But the strongest argument against the existence of the Britannic book is (not that it is not extant now, but) that the historians of the next generation never saw it. Geoffrey’s History at once created a tremendous stir in the literary world—nor was it accepted on trust—but received with suspicion and incredulity. Thus William of Newburgh, in the latter part of the twelfth century, calls Geoffrey roundly, “a saucy and shameless liar.” William, of course, did not know Welsh, and could not have made anything out of the Britannic book, even if he had seen it. This objection does not apply to Giraldus Cambrensis; his knowledge of Welsh was indeed slight—but he had plenty of Welsh-speaking relatives and friends, and he was himself a collector of manuscripts. Gerald refers to “the lying statements of Geoffrey’s fabulous history,” and implies in a much-quoted passage that he regarded Geoffrey’s history as a pack of lies. Speaking of a Welshman at Caerleon who had dealings with evil spirits, and was enabled by their assistance to foretell future events, he goes on: “He knew when any one told a lie in his presence, for he saw the devil dancing on the tongue of the liar. If the evil spirits oppressed him too much, the Gospel of St. John was placed on his bosom, when like birds they immediately vanished; but when the Gospel was removed, and the History of the Britons by Geoffrey Arthur was substituted in its place, the devils instantly came back in greater numbers, and remained a longer time than usual on his body and on the book.” Geoffrey may very probably have used some Britannic manuscript, but it could not have been very ancient; and he certainly did not translate it, but used it as he used Gildas and Bede and Nennius—sometimes quoting their statements, more generally amplifying them almost beyond recognition.

Was Geoffrey merely an inventor? Sometimes—undoubtedly. The long strings of names of purely fictitious princes whom the Roman Consul summoned to fight against King Arthur, at a time when in sober history Justinian was Roman Emperor, are invented by Geoffrey. And consider too his parodies of the practice of historians of referring to contemporary events: an instance of the genuine article is given in Gerald’s Itinerary. “In 1188, Urban III. being pope, Frederick, Emperor of the Romans, Isaac, Emperor of Constantinople, Philip, King of France,” &c., &c. Now take Geoffrey’s parodies: “At this time, Samuel the prophet governed in Judæa, Æneas was living, and Homer was esteemed a famous orator and poet.” Or again: “At the building of Shaftesbury an eagle spoke while the wall of the town was being built: and indeed I should have transmitted the speech to posterity, had I thought it true, like the rest of the history. At this time Haggai, Amos, Joel, and Azariah were prophets of Israel.” One may be quite sure that passages like these are not derived from the writings of the ancients, or from oral traditions. One can in some cases trace back his statements and see how much he added to his predecessors. A good instance is his account of the conversion of the Britons under King Lucius, in Bk. IV., cap. 19 and 20, and V., cap. 1 (a.d. 161). Geoffrey’s account is circumstantial: King Lucius sent to the Pope asking for instruction in the Christian religion. The Pope sent two teachers (whose names are given), who almost extinguished paganism over the whole island, dedicated the heathen temples to the true God, and substituted three archbishops for the three heathen archflamens at London, York, and Caerleon-on-Usk, and twenty-eight bishops for the twenty-eight heathen flamens. Now all this is based on a short passage in Bede: “Lucius King of the Britains sent to the Pope asking that he might be made a Christian; he soon obtained his desire, and the Britons kept the faith pure till the Diocletian persecution,” which itself is amplified from an entry in the Liber Pontificalis: “Lucius King of the Britains sent to the Pope asking that he might be made a Christian.” This last does not occur in the early version of the Liber Pontificalis, and is irreconcilable with the history and position of the papacy in the second century; but is a forgery, inserted at the end of the seventh century by the Romanising party in the Welsh Church—the party desiring to bring the Welsh Church into communion with the Roman, and so interested in proving that British Christianity came direct from the Pope; and all the talk about the archflamens and archbishops, &c., is pure invention. Notice too what an important part the places with which Geoffrey is specially connected play in his history: Caerleon is the seat of an archbishopric and favourite residence of Arthur; Oxford is frequently mentioned though it did not exist until the end of the ninth century; the Consul of Gloucester (predecessor of Geoffrey’s patron, Robert, Consul of Gloucester) makes the decisive move in Arthur’s battle with the Romans.

A parallel case is Geoffrey’s account of Brutus and the descent of the Britons from the Trojans. The tradition is found in Nennius, and perhaps dates from the classical revival at the court of Charlemagne. It is clearly not a popular tradition, but an artificial tradition of the learned; but whilst Geoffrey did not invent the legend, he invented all the details—letters and speeches, and hairbreadth escapes and tales of love and war.

Probably his detailed accounts of King Arthur’s European conquests—extending over nearly all Western Europe, from Iceland and Norway to Gaul and Italy—are still more the work of Geoffrey’s inventive genius, though it is possible they may rest on early Celtic myths about the voyage of Arthur to Hades, as Professor Rhys suggests, or on late Breton traditions which mixed up Arthur with Charles the Great.

Now let us consider Geoffrey as a gatherer and transmitter of the genuine oral traditions of the Welsh and Breton people. Genuine traditions are true history in the sense that they preserve manners and customs and modes of thought prevalent at the time when they became current. Thus they are on quite a different level from Geoffrey’s inventions, though they cannot be taken as containing the history of any of the individuals to whom they profess to relate. He tells us in his preface that the actions of Arthur and many others, though not mentioned by historians, “were celebrated by many people in a pleasant manner and by heart,” were sung by poets and handed down from generation to generation, like the poetical traditions of every people in primitive times. There can be no doubt that Geoffrey collected a number of these old stories and wove them into his narrative. Thus, the story of King Lear and his daughters has the ring of a genuine popular tradition about it, though the dates and pseudo-historical setting were probably supplied by Geoffrey. Again, there were certainly prophecies attributed to Merlin current in Geoffrey’s time. But one may suspect Geoffrey of doing a good deal more than translate the prophecies of Merlin; he adapted them; one may even suspect him of parodying them. “After him shall succeed the boar of Totness, and oppress the people with grievous tyranny. Gloucester shall send forth a lion and shall disturb him in his cruelty in several battles. The lion shall trample him under his feet ... and at last get upon the backs of the nobility. A bull shall come into the quarrel and strike the lion ... but shall break his horns against the walls of Oxford.” “Then shall two successively sway the sceptre, whom a horned dragon shall serve. One shall come in armour and ride upon a flying serpent. He shall sit upon its back with his naked body, and cast his right hand upon its tail.... The second shall ally with the lion; but a quarrel happening they shall encounter one another ... but the courage of the beast shall prevail. Then shall one come with a drum, and appease the rage of the lion. Therefore shall the people of the kingdom be at peace, and provoke the lion to a dose of physic!”

Then as to Arthur. In Geoffrey’s history he appears mainly as a great continental conqueror—a kind of Welsh Charlemagne. “Many of the most picturesque and significant features of the full-grown legend (as Professor Lewis Jones points out)[1] are not even faintly suggested by Geoffrey. The Round Table, Lancelot, the Grail were unknown to him, and were grafted on the legend from other sources.” But he made the Arthurian legends fashionable; he opened for all Europe the hitherto unknown and inexhaustible well of Celtic romance; and it may be said without exaggeration that “no mediæval work has left behind it so prolific a literary offspring as the History of the Kings of Britain.”

The value of Geoffrey is not in his fictions about past history, but in his influence on the literature and ideas of the future. He stands at the beginning of a new age: he is the first spokesman of the Age of the new Chivalry. Read his glowing account of Arthur’s court, where “the knights were famous for feats of chivalry, and the women esteemed none worthy of their love but such as had given proof of their valour in three several battles. Thus was the valour of the men an encouragement for the women’s chastity, and the love of the women a spur to the knight’s bravery.” Or, as an old French version has it, “Love which made the women more chaste made the knights more valorous and famous.” We have here a new conception of love which has profoundly influenced life and thought ever since—love no longer a weakness as in the ancient world, or a sin as it seemed to the ascetic spirit of the Church, but a conscious source of strength, an avowed motive of heroism. And it was round Arthur and his court that the French poets of the next generation wove their romances inspired by this conception—the offspring of the union of Norman strength and Celtic gentleness.

3. Giraldus Cambrensis

GERALD the Welshman was certainly one of the most remarkable men of letters that the Middle Ages produced—remarkable not merely for the great range of his knowledge, or the voluminousness of his writings, but for the originality of his views and variety of his interests.

In this lecture I intend to give first a general account of his life, and then deal in more detail with his Itinerary through Wales.

We know a great deal about Gerald; he was interested in many things, and not least in himself; he was not troubled by that shrinking sense of his own worthlessness—with the feeling of being not an individual, but a part of a community—which is so characteristic of mediæval writers, and led them often to omit to mention their own names.

Gerald was born about 1146, at Manorbier, in Pembroke—“the most delightful spot in Wales.” His ancestry is interesting. His father was a Norman noble, holding of Glamorgan, William de Barri by name; his mother was the daughter of another Norman noble, Gerald de Windsor of Pembroke, and the famous Nest, daughter of Rhys ap Tudor, the Helen of Wales. He was cousin of the Fitzgeralds who played so important a part in the conquest of Ireland, and connected with Richard Strongbow and the great house of Clare. He thus “moved in the highest circles,” and lived in an atmosphere of great deeds and great traditions.

He was from the first marked out by his own inclinations for an ecclesiastical career. He tells us that when he and his elder brothers used to play as children on the sands of Manorbier his brothers built castles but he always built churches. He received an elementary education from the chaplains of his uncle, the Bishop of St. David’s; he seems to have been slow at learning when a child, and his tutors goaded him on not by the birch rod, but by sarcasm—by declining “Stultus, stultior, stultissimus.” His higher education was not obtained in Wales, and it is singular that he does not notice any place of learning in Wales in all his writings. He studied at Gloucester, and then at Paris, the greatest mediæval university. We have it on his own authority that he was a model student. “So entirely devoted was he to study, having in his acts and in his mind, no sort of levity or coarseness, that whenever the Masters of Arts wished to select a pattern from among the good scholars, they would name Gerald before all others.” Later he lectured at Paris on canon law and theology; his lectures, he tells us, were very popular. He returned thence in 1172, two years after the martyrdom of Thomas Becket, whose example and struggle for the rights of the Church made a deep and lasting impression on him. Gerald soon obtained preferment: he held three livings in Pembroke, one in Oxfordshire, and canonries at Hereford and St. David’s. His energy soon made itself felt. He excommunicated the Welshmen and Flemings who would not pay tithes; and then attacked the sins of the clergy. Most of the Welsh clergy were married, contrary to the laws of the Church. Gerald hated a married priest even more than he hated a monk. The Welsh priest, he says, was wont to keep in his house a female (focaria) “to light his fire but extinguish his virtue.” “How can such a man practice frugality and self-denial with a house full of brawling brats, and a woman for ever extracting money to buy costly robes with long skirts trailing in the dust?” Gerald hated women—the origin of all evil since the world began: observing that in birds of prey the females are stronger than the males, he remarks that this signifies “the female sex is more resolute in all evil than the male.” Among the married clergy he attacked was the Archdeacon of Brecon; and the old man, being forced to choose between his wife and his archdeaconry, preferred his wife. Gerald was made Archdeacon of Brecon. In later years he had qualms of conscience about the part he took in this business.

Between 1180 and 1194 he was often at Court and employed in the king’s affairs. Henry II. selected him as a suitable person to accompany the young prince John to Ireland in 1185, and the result was his two great works—“The Topography,” and “The Conquest of Ireland,” which are the chief and almost the only authorities for Irish history in the Middle Ages. The former work he read publicly at Oxford on his return; it was a great occasion: we must tell it in his own words. “When the work was finished, not wishing to hide his candle under a bushel, but wishing to place it in a candlestick, so that it might give light, he resolved to read it before a vast audience at Oxford, where scholars in England chiefly flourished and excelled in scholarship. And as there were three divisions in the work, and each division occupied a day, the readings lasted three successive days. On the first day, he received and entertained at his lodgings all the poor people of the town; on the second, all the doctors of the different faculties and their best students; and on the third, the rest of the students and the chief men of the town. It was a costly and noble act; and neither present nor past time can furnish any record of such a solemnity having ever taken place in England.”

In 1188 he accompanied the Archbishop of Canterbury in his tour through Wales to preach the Third Crusade. With this we shall deal later.

He was abroad with Henry II. at the time of the old king’s death, and has left a valuable account of his later years in the book “On the Instruction of Princes.” His connection with the Court gave him opportunities for studying the great characters of the time at close quarters, and we have from his pen graphic sketches of many of them. Take this description of Henry II.: “He had a reddish complexion, rather dark, and a large round head. His eyes were gray, bloodshot, and flashed in anger. He had a fiery face; his voice was shaky; he had a deep chest, and long muscular arms, his great round head hanging somewhat forward. He had an enormous belly—though not from gross feeding. Indeed he was temperate in all things, for a prince. To keep down his corpulency, he took immoderate exercise. Even in times of peace he took no rest—hunting furiously all day, and on his return home in the evening seldom sitting down either before or after supper; for in spite of his own fatigue, he would weary out the Court by being constantly on his legs.”

The whole is very interesting and full of life. It occurs in the “Conquest of Ireland,” and is quoted in several of his other works. Gerald’s favourite author was Gerald of Barry, Archdeacon of Brecon.

The next important episode in his life was the struggle for St. David’s (1198-1203). It was really a fight for the independence of the Welsh Church from England and its direct dependence on the Pope. Gerald was elected bishop by the canons of St. David’s, in opposition to the will of King John (whose consent was necessary) and of Hubert Walter, Archbishop of Canterbury (whose rights as metropolitan were attacked). Gerald hastened off to Rome to get the Pope’s support, taking with him the most precious offering that he could think of—six of his own books; for Rome had a bad name for bribery—and who could resist such a bribe? But he found it advisable to supplement his books by other promises, especially by the offer to the Pope of tithes from Wales.

The Pope at this time was Innocent III.—the greatest of all the Popes—who brought kings and nations under his feet and held despotic sway over the Universal Church, and stamped out heresy in blood. In the references to him in Gerald’s works he appears in much more human guise. We see him after supper unbending and laughing at Gerald’s anecdotes and cracking jokes of a somewhat risky character with the archdeacon. It is clear that the Pope thoroughly enjoyed the Welshman’s company, but also that he did not take him very seriously as an ecclesiastical statesman. “Let us have some more stories about your archbishop’s bad Latin,” he would say, when Gerald was getting too urgent on the independence of the Welsh Church or his own right to the see of St. David’s.

This archbishop was Hubert Walter, who was much more of a secular administrator than an ecclesiastic, and whose Latin though clear and ready might show a fine contempt for all rules of grammar. Gerald was a stickler for correct Latin grammar; he is great on “howlers.” There is one of his stories, illustrating both the avarice of the Norman prelates and the ignorance of the Welsh clergy: A Welsh priest came to his bishop and said, “I have brought your lordship a present of two hundred oves.” He meant “ova”; but the bishop insisted on the sheep; and the priest probably rubbed up his Latin grammar. Gerald had also other patriotic reasons for his hostility to the archbishop, who as chief justiciary—i.e., chief minister of the king—had recently attacked and defeated the Welsh between the Wye and the Severn. “Blessed be God,” writes Gerald sarcastically to him, “who has taught your hands to war and your fingers to fight, for since the days when Harold almost exterminated the nation, no prince has destroyed so many Welshmen in one battle as your Grace.”

Gerald continued the struggle till 1203, though deserted by the Welsh clergy. “The laity of Wales,” he said, “stood by me; but of the clergy whose battle I was fighting, scarce one.” He was proclaimed as a rebel, and had some narrow escapes of imprisonment or worse—escapes which he owed to his ready wit and which he delights to tell. At last he gave way, and during the remainder of his life we find him at Rome, Lincoln, St. David’s, revising his works and writing new ones, modifying some of his judgments (especially that on Hubert Walter), and encouraging Stephen Langton in the great struggle against John. He was buried at St. David’s, probably in 1223.

We will now return to the “Itinerary through Wales” and the “Description of Wales.” Jerusalem was taken by Saladin in 1187, and the Third Crusade—the Crusade of Richard Cœur de Lion—was preached throughout Europe. In 1188 Archbishop Baldwin made a preaching tour through Wales accompanied by Glanville, the great justiciary of Henry II., and Gerald of Barry. While the primary object was the preaching of the Crusade, the king had an eye to business and saw that the Holy Cause could be utilised for other purposes; it gave an opportunity for the assertion of the metropolitan rights of Canterbury over the Welsh Church, and for a survey of the country by the royal officials, which was not possible under other circumstances. That is why the archbishop and the justiciar accompanied the expedition. It is remarkable that Gerald, the champion of the Welsh Church, should have given his support to it; but he had not fully adopted the patriotic attitude of his later years; and, with him as with most people of the time, the rescue of the Holy Sepulchre was, in theory at any rate, the greatest object in the world; while further, we must not forget that the journey had many attractions for him as an author; it gave him “copy” for a new book, and the chance of reading his Irish Topography to the archbishop. Every day during the journey the archbishop listened to a portion of this book, and at the end took it home to finish. As the journey lasted at least fifty days, one may calculate that it took at most an average of three pages a day to send the archbishop to sleep.

The Itinerary (which was later dedicated to Stephen Langton) contains in the author’s words an account of “the difficult places through which we passed, the names of springs and torrents, the witty sayings, the toils and incidents of the journey, the memorable events of ancient and modern times, and the natural history and description of the country.”

The route pursued was as follows: From Hereford to Radnor, Brecon, Abergavenny, Caerleon, Newport, Cardiff, Llandaff, Ewenny, Margam, Swansea, Kidweli, Carmarthen, Haverford, St. David’s, Cardigan, Strata Florida, thence keeping close to the coast, through Bangor and Chester; and then south by Oswestry, Shrewsbury, Ludlow, to Hereford.

The travellers were well received and entertained both by the Lords Marcher and the Welsh princes. It was especially to the Welsh that their attention was directed, and Welsh princes accompanied them through their territories. The chief was Rhys ap Gruffydd (Gerald’s uncle), prince of South Wales, who was then at the height of his power, and had been made chief justice of South Wales by Henry II., to whom he faithfully adhered. Gwynedd and Powys were then divided among several heirs. One of the princes of Powys, Owain Cyfeiliog, the poet, was distinguished as being the only prince who did not come to meet the archbishop with his people; for which he was excommunicated. Gerald notes that he was an adherent of Henry II., and was “conspicuous for the good management of his territory.” Perhaps that is why he would not have anything to do with the Crusade.

How far was the expedition successful in its primary object in gaining crusaders? The archbishop and justiciar had already taken the cross; they remained true to their vows and went to the Holy Land, the archbishop dying at the siege of Acre, heartbroken at the wickedness of the army. Gerald himself was the first to take the cross in Wales, not acting under the influence of religious enthusiasm, but (as he says himself) “impelled by the urgent requests and promises of the king and persuasions of the archbishop,” who wanted him to act as historian; but Gerald, after setting the example, bought a dispensation and did not go. A number of the lesser Welsh princes soon took the cross. The Lord Rhys himself was eager to do so, but “his wife by female artifices diverted him wholly from his noble purpose.” The wives were all dead against the whole affair. At Hay the wives caught hold of their husbands, and the would-be Crusaders had literally to run away from them to the castle, leaving their cloaks behind them. A nobler spirit of self-sacrifice was shown by the old woman of Cardigan, who, when her only son took the cross, said: “O most beloved Lord Jesus Christ, I give Thee hearty thanks for having conferred on me the blessing of bringing forth a son worthy of Thy service.” This son was probably worth more than the twelve archers of the castle of St. Clears who were forcibly signed with the cross for committing a murder; and one may reasonably look with suspicion on the sudden conversion of “many of the most notorious murderers and robbers of the neighbourhood” at Usk. It was this kind of thing that turned the Holy Land into a sort of convict settlement.

The preachers clearly worked hard and had some trying experiences, and kept up their spirits by little jokes, which Gerald retails. They nearly came to grief in quicksands at the mouth of the river Neath. “Terrible hard country this,” said one of the monks next day in the castle at Swansea. “Some people are never satisfied,” retorted his companion; “you were complaining of its being too soft in the quicksand yesterday.” The mountains were trying to men no longer in their youth; after toiling up one the archbishop sank exhausted on a fallen tree and said to his panting companions, “Can any one enliven the company by whistling a tune?” “Which,” adds Gerald, “is not very easily done by people out of breath.” From whistling the conversation passed to nightingales, which some one said were never found in Wales. “Wise bird, the nightingale,” remarked the archbishop.

One serious difficulty they had was that none of them, not even Gerald, knew Welsh sufficiently well to preach in it, though they generally had interpreters. The archbishop, who would sometimes preach away for hours without result, felt this much more than Gerald. He declares he moved crowds to tears though they did not understand a word of what he was saying. But one may take the words of Prince Rhys’s fool as evidence (if any were needed) that ignorance of Welsh weakened the effect. “You owe a great debt, Rhys, to your kinsman the archdeacon, who has taken a hundred or so of your men to serve the Lord; if he had only spoken in Welsh, you wouldn’t have had a soul left.”

In all about three thousand took the cross; but the Crusade was delayed, zeal cooled, and it is probable that comparatively few went. The Itinerarium Regis Ricardi mentions, I think, only one exploit by a Welshman in the Third Crusade; he was an archer, and so a South Walian.

This brings me to one of the incidental notes of great value scattered about the Itinerary. Speaking of the siege of Abergavenny (1182), Gerald tells us that the men of Gwent and Glamorgan excelled all others in the use of the bow, and gives curious evidence of the strength of their shooting. Thus the arrows pierced an oak door four inches thick; they had been left there as a curiosity, and Gerald saw them with their iron points coming through on the inner side. He describes these bows as “made of elm—ugly, unfinished-looking weapons, but astonishingly stiff, large, and strong, and equally useful for long and short shooting.” Add to this that the longbow was not a characteristic English weapon till the latter part of the thirteenth century, that the first battle in which an English king made effective use of archery (at Falkirk, 1298), his infantry consisted mainly of Welshmen; and there can be little doubt that the famous longbow of England, which won the victories of Creçy and Poitiers and Agincourt, and indirectly did much to destroy feudalism and villenage, had its home in South Wales.

Gerald was also a keen observer of nature, and his knowledge of the ways of animals is extensive and peculiar. Perhaps even more marked is his love of the supernatural; he could believe anything, if it was only wonderful enough—except Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History. But I must confine myself to one story—the story of the boy in Gower who (as the root of learning is bitter) played truant and found two little men of pigmy stature, and went with them to their country under the earth, and played games with golden balls with the fairy prince. These little folk were very small—of fair complexion, and long luxuriant hair; and they had horses and dogs to suit their size. They hated nothing so much as lies; “they had no form of public worship, being lovers and reverers, it seemed, of truth.” The boy often went, till he tried to steal a golden ball, and then he could never find fairyland again. But he learnt some of the fairy language, which was like Greek. And then Gerald compares words in different languages, and notes how, for instance, the same word for salt runs through Greek and British and Irish and Latin and French and English and German, and the fairy language, which suggests a close relation between all these peoples in past ages. It is very modern; and it is not without reason that Gerald has been called “the father of comparative philology.”

In his “Description of Wales” Gerald describes the manner of life and characteristics of the people. All are trained to arms, and when the trumpet sounds the alarm, the husbandman rushes as eagerly from his plough as the courtier from his court. Agricultural work takes up little of their time, as they are still mainly in a pastoral stage, living on the produce of their herds, and eating more meat than bread. They fight and undergo hardships and willingly sacrifice their lives for their country and for liberty. They wear little defensive armour, and depend mainly on their mobility; they are not much good at a close engagement, but generally victors in a running fight, relying more on their activity than on their strength.

It was the fashion to keep open house for all comers. “Those who arrive in the morning are entertained till evening with the conversation of young women and the music of the harp; for each house has its young women and harps allotted for the purpose. In each family the art of playing on the harp is held preferable to any other learning; and no nation is so free from jealousy as the Welsh.” After a simple supper (for the people are not addicted to gluttony or drunkenness), “a bed of rushes is placed along the side of the hall, and all in common lie down to sleep with their feet towards the fire. They sleep in the thin cloak and tunic they wear by day. They receive much comfort from the natural heat of the persons lying near them; but when the underside begins to be tired with the hardness of the bed, or the upper one to suffer from the cold, they get up and go to the fire; and then returning to the couch they expose their sides alternately to the cold and to the hardness of the bed.”

Gifted with an acute and rich intellect they excel in whatever studies they pursue, notably in music. They are especially famous for their part-singing, “so that in a company of singers, which one very often meets with in Wales, you will hear as many different parts and voices as there are performers,”(!) and this gift has by long habit become natural to the nation.

“They show a greater respect than other nations to churches and ecclesiastics, to the relics of saints, bells, holy books, and the cross; and hence their churches enjoy more than common tranquillity.”

He then goes on to the other side of the picture: “for history without truth becomes undeserving of its name.” “These people are no less light in mind than in body, and by no means to be relied on. They are easily urged to undertake any action, and as easily checked from prosecuting it.... They never scruple at taking a false oath for the sake of any temporary advantage.... Above all other peoples they are given to removing their neighbours’ landmarks. Hence arise quarrels, murders, conflagrations, and frequent fratricides. It is remarkable that brothers show more affection to each other when dead than when living; for they persecute the living even unto death, but avenge the dead with all their power.”

Finally, as a scientific observer of politics, he discusses how Wales may be conquered and governed, and how the Welsh may resist.

A prince who would subdue this people must give his whole energies to the task for at least a whole year. He must divide their strength, and by bribes and promises endeavour to stir up one against the other, knowing the spirit of hatred and envy which generally prevails among them. He must cut off supplies, build castles, and use light-armed troops and plenty of them; for though many English mercenaries perish in a battle, money will procure as many more; but to the Welsh the loss is for the time irreparable. He recommends that all the English inhabitants of the Marches should be trained to arms; for the Welsh fight for liberty and only a free people can subdue them. His advice to the Welsh is: Unite. “If they would be inseparable, they would be insuperable, being assisted by these three circumstances—a country well defended by nature, a people contented to live upon little, a community whose nobles and commoners alike are trained in the use of arms; and especially as the English fight for power, the Welsh for liberty; the English hirelings for money, the Welsh patriots for their country.”

I hope I may persuade some who do not yet know Gerald to make his acquaintance, and to read either his works on Ireland and Wales, translated in Bohn’s library, or Mr. Henry Owen’s brilliant and delightful volume, “Gerald the Welshman,” my indebtedness to which I wish to acknowledge. Gerald tells us many miracles; but he has himself performed a miracle as wonderful as any he relates; he has kept all the charm and freshness of youth for more than seven hundred years.

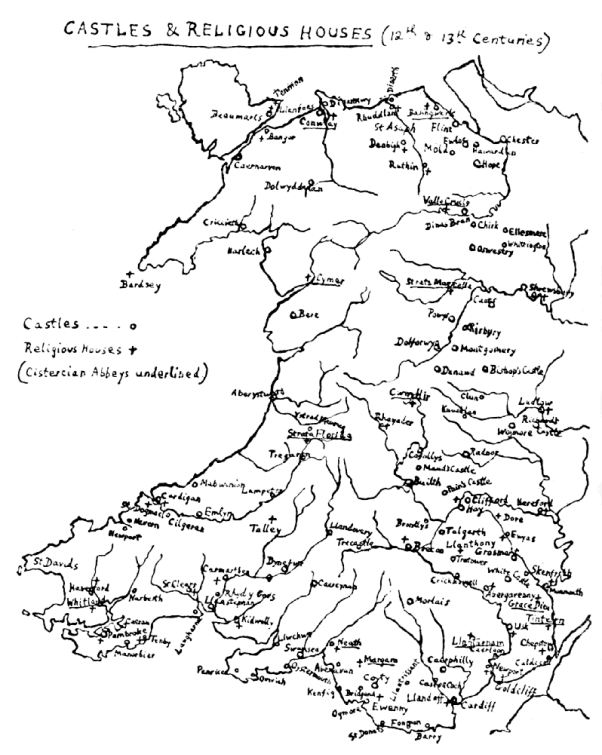

4. Castles

WALES is pre-eminently the land of castles. There are between thirty and forty in Glamorgan alone. The accompanying map, though it is by no means exhaustive, shows the general lie of the castles, which may be divided into three groups, having as their respective bases Chester, Shrewsbury, and Gloucester. But though there is some evidence of an organised plan for the conquest of Wales in the time of William Rufus, it is useless to look for any great and general system of offence or defence, because most of the castles were not built by a centralised government with any such object in view, but by individuals to guard their own territories and protect their independence against either their neighbours or the English king. The great age of castle-building was between 1100 and 1300. Castles play a very small part in the fighting in Wales till the end of the eleventh century. Before that time indeed there were few stone castles anywhere; the usual type, even of the early Norman castles, was a moated mound surrounded by wooden palisades. One hears for instance of a castle being built by William the Conqueror in eight days. An example of this early type of fortress was Pembroke Castle at the end of the eleventh century, “a slender fortress of stakes and turf,” which had the good fortune to be in charge of Gerald of Windsor, grandfather of Giraldus Cambrensis. It stood several sieges, which shows that the siege engines of the Welsh were of a very poor and primitive type. One of these sieges was turned into a blockade, and the garrison was nearly reduced by starvation. The constable had recourse to a time-honoured ruse. “With great prudence he caused four hogs which still remained to be cut into small pieces and thrown down among the enemy. The next day he had recourse to a more refined stratagem: he contrived that a letter from him should fall into the hands of the enemy stating that there was no need for assistance for the next four months.” The besiegers were taken in and dispersed to their homes.

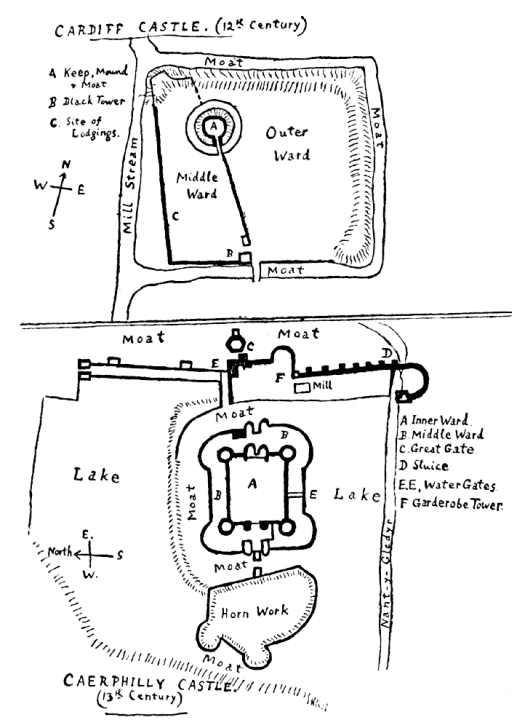

The characteristic types of castles in the twelfth century were the rectangular keep and the shell keep; in the thirteenth the concentric castle. Of the two last we have splendid examples in Cardiff and Caerphilly. Of rectangular keeps there are very few in Wales—Chepstow is the only important one—though there are several on the borders, notably Ludlow. The square keep seems to us most characteristic of Norman military architecture; the Tower of London, Rochester, Newcastle, Castle Rising, are well-known examples, and there are many more in a good state of preservation; there are many more solid square keeps than shell keeps well preserved, but this is simply due to the greater solidity of the former; the shell keeps were far more numerous in the twelfth century; and the reasons for this are obvious—the rectangular keep was much more expensive to build, and it was too heavy to erect on the artificial mounds on which the Norman architects generally founded their castles.

The keep of Cardiff Castle is one of the most perfect shell keeps in existence. It is built on a round artificial mound, surrounded by a wide and deep moat—the mound and moat being, of course, complements of each other. Such mounds and moats are common in all parts of England, and in Normandy. They are not Roman, nor British, nor are they, as Mr. G. T. Clark maintained, characteristic of Anglo-Saxon work. They are essentially Norman, and a good representation of the making of such a mound may be seen in the Bayeux Tapestry, under the heading—‘He orders them to dig a castle.’ When was the Cardiff mound made? Perhaps the short entry in the Brut gives the answer: “1080, the building of Cardiff began.” It would then be surrounded by wooden palisades, and surmounted by a timber structure, as a newly made mound would not stand the masonry. The shell keep was probably built by Robert of Gloucester, and it was probably in the gate-house of this keep, that Robert of Normandy was imprisoned. A shell keep was a ring wall eight or ten feet thick, about thirty feet high, not covered in, and enclosing an open courtyard, round which were placed the buildings—light structures, often wooden sheds, abutting on the ring wall—such as one may see now in the courtyard of Castell Coch. The shell keep was the centre of Robert’s castle, but not the whole. From this time dated the great outer walls on the south and west—walls forty feet high and ten feet thick and solid throughout. The north and east and part of the south sides of the castle precincts are enclosed by banks of earth, beneath which, the walls of a Roman camp have recently been discovered. These banks were capped by a slight embattled wall. Outside along the north, south and east fronts was a moat, formerly fed by the Taff through the Mill leat stream which ran along the west front. The present lodgings, or habitable part of the castle built on either side of the great west wall, date mostly from the fifteenth century. The earlier lodgings were, perhaps, on the same site—though only inside the wall; a great lord did not as a rule live in the keep, except in times of danger.

The area of the enclosure is about ten acres—more suited to a Roman garrison than to a lord marcher of the twelfth century. That the castle was difficult to guard is shown by the success of Ivor Bach’s bold dash, c. 1153-1158. Ivor ap Meyric was Lord of Senghenydd, holding it of William of Gloucester, the Lord of Glamorgan, and, perhaps, had his headquarters in the fortress above the present Castell Coch. “He was,” says Giraldus Cambrensis, “after the manner of the Welsh, owner of a tract of mountain land, of which the earl was trying to deprive him. At that time the Castle of Cardiff was surrounded with high walls, guarded by 120 men at arms, a numerous body of archers and a strong watch. Yet in defiance of all this, Ivor, in the dead of night secretly scaled the walls, seized the earl and countess and their only son, and carried them off to the woods; and did not release them till he had recovered all that had been unjustly taken from him,” and a goodly ransom in addition. Perhaps the most permanent result of this episode was the building of a wall 30 feet high between the keep and the Black Tower—dividing the castle enclosure into two parts and forming an inner or middle ward of less extent, and less liable to danger from such sudden raids.