The World as Will and Idea

by

Arthur Schopenhauer

First published in 1818.

This translation by R. B. Haldane and J. Kemp was published in 1909.

Table of Contents

Second Book. The World As Will

First Aspect. The Objectification Of The Will

Fourth Book. The World As Will

Appendix: Criticism Of The Kantian Philosophy

First Half. The Doctrine Of The Idea Of Perception. (To § 1-7 Of The First Volume)

II. The Doctrine Of Perception Or Knowledge Of The Understanding

Second Half. The Doctrine Of The Abstract Idea, Or Thinking

V. On The Irrational Intellect

VI. On The Doctrine Of Abstract Or Rational Knowledge

VII. On The Relation Of The Concrete Knowledge Of Perception To Abstract Knowledge

VIII. On The Theory Of The Ludicrous

XII. On The Doctrine Of Science

XIII. On The Methods Of Mathematics

XIV. On The Association Of Ideas

XV. On The Essential Imperfections Of The Intellect

XVI. On The Practical Use Of Reason And On Stoicism

XVII. On Man’s Need Of Metaphysics

Supplements To The Second Book

XVIII. On The Possibility Of Knowing The Thing In Itself

XIX. On The Primacy Of The Will In Self-Consciousness

XX. Objectification Of The Will In The Animal Organism

Note On What Has Been Said About Bichat

Supplements To The Second Book

XXI. Retrospect And More General View

XXII. Objective View Of The Intellect

XXIII. On The Objectification Of The Will In Unconscious Nature

XXV. Transcendent Considerations Concerning The Will As Thing In Itself

XXVII. On Instinct And Mechanical Tendency

XXVIII. Characterisation Of The Will To Live

XXIX. On The Knowledge Of The Ideas

XXX. On The Pure Subject Of Knowledge

XXXIII. Isolated Remarks On Natural Beauty

XXXIV. On The Inner Nature Of Art

XXXV. On The Æsthetics Of Architecture

XXXVI. Isolated Remarks On The Æsthetics Of The Plastic And Pictorial Arts

XXXVII. On The Æsthetics Of Poetry

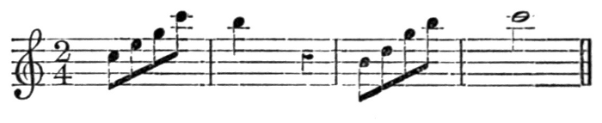

XXXIX. On The Metaphysics Of Music

Supplements To The Fourth Book

XLI. On Death And Its Relation To The Indestructibility Of Our True Nature

XLIV. The Metaphysics Of The Love Of The Sexes

XLV. On The Assertion Of The Will To Live

XLVI. On The Vanity And Suffering Of Life

XLVIII. On The Doctrine Of The Denial Of The Will To Live

Translators’ Preface

The style of “Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung” is sometimes loose and involved, as is so often the case in German philosophical treatises. The translation of the book has consequently been a matter of no little difficulty. It was found that extensive alteration of the long and occasionally involved sentences, however likely to prove conducive to a satisfactory English style, tended not only to obliterate the form of the original but even to imperil the meaning. Where a choice has had to be made, the alternative of a somewhat slavish adherence to Schopenhauer’s ipsissima verba has accordingly been preferred to that of inaccuracy. The result is a piece of work which leaves much to be desired, but which has yet consistently sought to reproduce faithfully the spirit as well as the letter of the original.

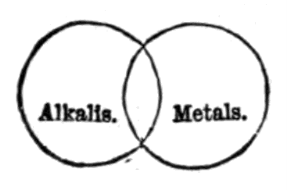

As regards the rendering of the technical terms about which there has been so much controversy, the equivalents used have only been adopted after careful consideration of their meaning in the theory of knowledge. For example, “Vorstellung” has been rendered by “idea,” in preference to “representation,” which is neither accurate, intelligible, nor elegant. “Idee,” is translated by the same word, but spelled with a capital, - “Idea.” Again, ”Anschauung” has been rendered according to the context, either by “perception” simply, or by “intuition or perception.”

Notwithstanding statements to the contrary in the text, the book is probably quite intelligible in itself, apart from the treatise “On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason.” It has, however, been considered desirable to add an abstract of the latter work in an appendix to the third volume of this translation.

R. B. H.

J. K.

Preface To The First Edition

I propose to point out here how this book must be read in order to be thoroughly understood. By means of it I only intend to impart a single thought. Yet, notwithstanding all my endeavours, I could find no shorter way of imparting it than this whole book. I hold this thought to be that which has very long been sought for under the name of philosophy, and the discovery of which is therefore regarded by those who are familiar with history as quite as impossible as the discovery of the philosopher’s stone, although it was already said by Pliny: Quam multa fieri non posse, priusquam sint facta, judicantur? (Hist. nat. 7, 1.)

According as we consider the different aspects of this one thought which I am about to impart, it exhibits itself as that which we call metaphysics, that which we call ethics, and that which we call æsthetics; and certainly it must be all this if it is what I have already acknowledged I take it to be.

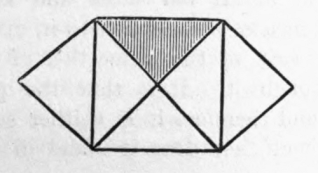

A system of thought must always have an architectonic connection or coherence, that is, a connection in which one part always supports the other, though the latter does not support the former, in which ultimately the foundation supports all the rest without being supported by it, and the apex is supported without supporting. On the other hand, a single thought, however comprehensive it may be, must preserve the most perfect unity. If it admits of being broken up into parts to facilitate its communication, the connection of these parts must yet be organic, i.e., it must be a connection in which every part supports the whole just as much as it is supported by it, a connection in which there is no first and no last, in which the whole thought gains distinctness through every part, and even the smallest part cannot be completely understood unless the whole has already been grasped. A book, however, must always have a first and a last line, and in this respect will always remain very unlike an organism, however like one its content may be: thus form and matter are here in contradiction.

It is self-evident that under these circumstances no other advice can be given as to how one may enter into the thought explained in this work than to read the book twice, and the first time with great patience, a patience which is only to be derived from the belief, voluntarily accorded, that the beginning presupposes the end almost as much as the end presupposes the beginning, and that all the earlier parts presuppose the later almost as much as the later presuppose the earlier. I say ”almost;” for this is by no means absolutely the case, and I have honestly and conscientiously done all that was possible to give priority to that which stands least in need of explanation from what follows, as indeed generally to everything that can help to make the thought as easy to comprehend and as distinct as possible. This might indeed to a certain extent be achieved if it were not that the reader, as is very natural, thinks, as he reads, not merely of what is actually said, but also of its possible consequences, and thus besides the many contradictions actually given of the opinions of the time, and presumably of the reader, there may be added as many more which are anticipated and imaginary. That, then, which is really only misunderstanding, must take the form of active disapproval, and it is all the more difficult to recognise that it is misunderstanding, because although the laboriously-attained clearness of the explanation and distinctness of the expression never leaves the immediate sense of what is said doubtful, it cannot at the same time express its relations to all that remains to be said. Therefore, as we have said, the first perusal demands patience, founded on confidence that on a second perusal much, or all, will appear in an entirely different light. Further, the earnest endeavour to be more completely and even more easily comprehended in the case of a very difficult subject, must justify occasional repetition. Indeed the structure of the whole, which is organic, not a mere chain, makes it necessary sometimes to touch on the same point twice. Moreover this construction, and the very close connection of all the parts, has not left open to me the division into chapters and paragraphs which I should otherwise have regarded as very important, but has obliged me to rest satisfied with four principal divisions, as it were four aspects of one thought. In each of these four books it is especially important to guard against losing sight, in the details which must necessarily be discussed, of the principal thought to which they belong, and the progress of the whole exposition. I have thus expressed the first, and like those which follow, unavoidable demand upon the reader, who holds the philosopher in small favour just because he himself is a philosopher.

The second demand is this, that the introduction be read before the book itself, although it is not contained in the book, but appeared five years earlier under the title, ”Ueber die vierfache Wurzel des Satzes vom zureichenden Grunde: eine philosophische Abhandlung” (On the fourfold root of the principle of sufficient reason: a philosophical essay). Without an acquaintance with this introduction and propadeutic it is absolutely impossible to understand the present work properly, and the content of that essay will always be presupposed in this work just as if it were given with it. Besides, even if it had not preceded this book by several years, it would not properly have been placed before it as an introduction, but would have been incorporated in the first book. As it is, the first book does not contain what was said in the earlier essay, and it therefore exhibits a certain incompleteness on account of these deficiencies, which must always be supplied by reference to it. However, my disinclination was so great either to quote myself or laboriously to state again in other words what I had already said once in an adequate manner, that I preferred this course, notwithstanding the fact that I might now be able to give the content of that essay a somewhat better expression, chiefly by freeing it from several conceptions which resulted from the excessive influence which the Kantian philosophy had over me at the time, such as—categories, outer and inner sense, and the like. But even there these conceptions only occur because as yet I had never really entered deeply into them, therefore only by the way and quite out of connection with the principal matter. The correction of such passages in that essay will consequently take place of its own accord in the mind of the reader through his acquaintance with the present work. But only if we have fully recognised by means of that essay what the principle of sufficient reason is and signifies, what its validity extends to, and what it does not extend to, and that that principle is not before all things, and the whole world merely in consequence of it, and in conformity to it, a corollary, as it were, of it; but rather that it is merely the form in which the object, of whatever kind it may be, which is always conditioned by the subject, is invariably known so far as the subject is a knowing individual: only then will it be possible to enter into the method of philosophy which is here attempted for the first time, and which is completely different from all previous methods.

But the same disinclination to repeat myself word for word, or to say the same thing a second time in other and worse words, after I have deprived myself of the better, has occasioned another defect in the first book of this work. For I have omitted all that is said in the first chapter of my essay ”On Sight and Colour,” which would otherwise have found its place here, word for word. Therefore the knowledge of this short, earlier work is also presupposed.

Finally, the third demand I have to make on the reader might indeed be tacitly assumed, for it is nothing but an acquaintance with the most important phenomenon that has appeared in philosophy for two thousand years, and that lies so near us: I mean the principal writings of Kant. It seems to me, in fact, as indeed has already been said by others, that the effect these writings produce in the mind to which they truly speak is very like that of the operation for cataract on a blind man: and if we wish to pursue the simile further, the aim of my own work may be described by saying that I have sought to put into the hands of those upon whom that operation has been successfully performed a pair of spectacles suitable to eyes that have recovered their sight—spectacles of whose use that operation is the absolutely necessary condition. Starting then, as I do to a large extent, from what has been accomplished by the great Kant, I have yet been enabled, just on account of my earnest study of his writings, to discover important errors in them. These I have been obliged to separate from the rest and prove to be false, in order that I might be able to presuppose and apply what is true and excellent in his doctrine, pure and freed from error. But not to interrupt and complicate my own exposition by a constant polemic against Kant, I have relegated this to a special appendix. It follows then, from what has been said, that my work presupposes a knowledge of this appendix just as much as it presupposes a knowledge of the philosophy of Kant; and in this respect it would therefore be advisable to read the appendix first, all the more as its content is specially related to the first book of the present work. On the other hand, it could not be avoided, from the nature of the case, that here and there the appendix also should refer to the text of the work; and the only result of this is, that the appendix, as well as the principal part of the work, must be read twice.

The philosophy of Kant, then, is the only philosophy with which a thorough acquaintance is directly presupposed in what we have to say here. But if, besides this, the reader has lingered in the school of the divine Plato, he will be so much the better prepared to hear me, and susceptible to what I say. And if, indeed, in addition to this he is a partaker of the benefit conferred by the Vedas, the access to which, opened to us through the Upanishads, is in my eyes the greatest advantage which this still young century enjoys over previous ones, because I believe that the influence of the Sanscrit literature will penetrate not less deeply than did the revival of Greek literature in the fifteenth century: if, I say, the reader has also already received and assimilated the sacred, primitive Indian wisdom, then is he best of all prepared to hear what I have to say to him. My work will not speak to him, as to many others, in a strange and even hostile tongue; for, if it does not sound too vain, I might express the opinion that each one of the individual and disconnected aphorisms which make up the Upanishads may be deduced as a consequence from the thought I am going to impart, though the converse, that my thought is to be found in the Upanishads, is by no means the case.

But most readers have already grown angry with impatience, and burst into reproaches with difficulty kept back so long. How can I venture to present a book to the public under conditions and demands the first two of which are presumptuous and altogether immodest, and this at a time when there is such a general wealth of special ideas, that in Germany alone they are made common property through the press, in three thousand valuable, original, and absolutely indispensable works every year, besides innumerable periodicals, and even daily papers; at a time when especially there is not the least deficiency of entirely original and profound philosophers, but in Germany alone there are more of them alive at the same time, than several centuries could formerly boast of in succession to each other? How is one ever to come to the end, asks the indignant reader, if one must set to work upon a book in such a fashion?

As I have absolutely nothing to advance against these reproaches, I only hope for some small thanks from such readers for having warned them in time, so that they may not lose an hour over a book which it would be useless to read without complying with the demands that have been made, and which should therefore be left alone, particularly as apart from this we might wager a great deal that it can say nothing to them, but rather that it will always be only pancorum hominum, and must therefore quietly and modestly wait for the few whose unusual mode of thought may find it enjoyable. For apart from the difficulties and the effort which it requires from the reader, what cultured man of this age, whose knowledge has almost reached the august point at which the paradoxical and the false are all one to it, could bear to meet thoughts almost on every page that directly contradict that which he has yet himself established once for all as true and undeniable? And then, how disagreeably disappointed will many a one be if he finds no mention here of what he believes it is precisely here he ought to look for, because his method of speculation agrees with that of a great living philosopher,[1] who has certainly written pathetic books, and who only has the trifling weakness that he takes all he learned and approved before his fifteenth year for inborn ideas of the human mind. Who could stand all this? Therefore my advice is simply to lay down the book.

But I fear I shall not escape even thus. The reader who has got as far as the preface and been stopped by it, has bought the book for cash, and asks how he is to be indemnified. My last refuge is now to remind him that he knows how to make use of a book in several ways, without exactly reading it. It may fill a gap in his library as well as many another, where, neatly bound, it will certainly look well. Or he can lay it on the toilet-table or the tea-table of some learned lady friend. Or, finally, what certainly is best of all, and I specially advise it, he can review it.

***********************************

And now that I have allowed myself the jest to which in this two-sided life hardly any page can be too serious to grant a place, I part with the book with deep seriousness, in the sure hope that sooner or later it will reach those to whom alone it can be addressed; and for the rest, patiently resigned that the same fate should, in full measure, befall it, that in all ages has, to some extent, befallen all knowledge, and especially the weightiest knowledge of the truth, to which only a brief triumph is allotted between the two long periods in which it is condemned as paradoxical or disparaged as trivial. The former fate is also wont to befall its author. But life is short, and truth works far and lives long: let us speak the truth.

Written at Dresden in August 1818.

Preface To The Second Edition

Not to my contemporaries, not to my compatriots—to mankind I commit my now completed work in the confidence that it will not be without value for them, even if this should be late recognised, as is commonly the lot of what is good. For it cannot have been for the passing generation, engrossed with the delusion of the moment, that my mind, almost against my will, has uninterruptedly stuck to its work through the course of a long life. And while the lapse of time has not been able to make me doubt the worth of my work, neither has the lack of sympathy; for I constantly saw the false and the bad, and finally the absurd and senseless,[2] stand in universal admiration and honour, and I bethought myself that if it were not the case those who are capable of recognising the genuine and right are so rare that we may look for them in vain for some twenty years, then those who are capable of producing it could not be so few that their works afterwards form an exception to the perishableness of earthly things; and thus would be lost the reviving prospect of posterity which every one who sets before himself a high aim requires to strengthen him.

Whoever seriously takes up and pursues an object that does not lead to material advantages, must not count on the sympathy of his contemporaries. For the most part he will see, however, that in the meantime the superficial aspect of that object becomes current in the world, and enjoys its day; and this is as it should be. The object itself must be pursued for its own sake, otherwise it cannot be attained; for any design or intention is always dangerous to insight. Accordingly, as the whole history of literature proves, everything of real value required a long time to gain acceptance, especially if it belonged to the class of instructive, not entertaining, works; and meanwhile the false flourished. For to combine the object with its superficial appearance is difficult, when it is not impossible. Indeed that is just the curse of this world of want and need, that everything must serve and slave for these; and therefore it is not so constituted that any noble and sublime effort, like the endeavour after light and truth, can prosper unhindered and exist for its own sake. But even if such an endeavour has once succeeded in asserting itself, and the conception of it has thus been introduced, material interests and personal aims will immediately take possession of it, in order to make it their tool or their mask. Accordingly, when Kant brought philosophy again into repute, it had soon to become the tool of political aims from above, and personal aims from below; although, strictly speaking, not philosophy itself, but its ghost, that passes for it. This should not really astonish us; for the incredibly large majority of men are by nature quite incapable of any but material aims, indeed they can conceive no others. Thus the pursuit of truth alone is far too lofty and eccentric an endeavour for us to expect all or many, or indeed even a few, faithfully to take part in. If yet we see, as for example at present in Germany, a remarkable activity, a general moving, writing, and talking with reference to philosophical subjects, we may confidently assume that, in spite of solemn looks and assurances, only real, not ideal aims, are the actual primum mobile, the concealed motive of such a movement; that it is personal, official, ecclesiastical, political, in short, material ends that are really kept in view, and consequently that mere party ends set the pens of so many pretended philosophers in such rapid motion. Thus some design or intention, not the desire of insight, is the guiding star of these disturbers of the peace, and truth is certainly the last thing that is thought of in the matter. It finds no partisans; rather, it may pursue its way as silently and unheeded through such a philosophical riot as through the winter night of the darkest century bound in the rigid faith of the church, when it was communicated only to a few alchemists as esoteric learning, or entrusted it may be only to the parchment. Indeed I might say that no time can be more unfavourable to philosophy than that in which it is shamefully misused, on the one hand to further political objects, on the other as a means of livelihood. Or is it believed that somehow, with such effort and such a turmoil, the truth, at which it by no means aims, will also be brought to light? Truth is no prostitute, that throws herself away upon those who do not desire her; she is rather so coy a beauty that he who sacrifices everything to her cannot even then be sure of her favour.

If Governments make philosophy a means of furthering political ends, learned men see in philosophical professorships a trade that nourishes the outer man just like any other; therefore they crowd after them in the assurance of their good intentions, that is, the purpose of subserving these ends. And they keep their word: not truth, not clearness, not Plato, not Aristotle, but the ends they were appointed to serve are their guiding star, and become at once the criterion of what is true, valuable, and to be respected, and of the opposites of these. Whatever, therefore, does not answer these ends, even if it were the most important and extraordinary things in their department, is either condemned, or, when this seems hazardous, suppressed by being unanimously ignored. Look only at their zeal against pantheism; will any simpleton believe that it proceeds from conviction? And, in general, how is it possible that philosophy, degraded to the position of a means of making one’s bread, can fail to degenerate into sophistry? Just because this is infallibly the case, and the rule, ”I sing the song of him whose bread I eat,” has always held good, the making of money by philosophy was regarded by the ancients as the characteristic of the sophists. But we have still to add this, that since throughout this world nothing is to be expected, can be demanded, or is to be had for gold but mediocrity, we must be contented with it here also. Consequently we see in all the German universities the cherished mediocrity striving to produce the philosophy which as yet is not there to produce, at its own expense and indeed in accordance with a predetermined standard and aim, a spectacle at which it would be almost cruel to mock.

While thus philosophy has long been obliged to serve entirely as a means to public ends on the one side and private ends on the other, I have pursued the course of my thought, undisturbed by them, for more than thirty years, and simply because I was obliged to do so and could not help myself, from an instinctive impulse, which was, however, supported by the confidence that anything true one may have thought, and anything obscure one may have thrown light upon, will appeal to any thinking mind, no matter when it comprehends it, and will rejoice and comfort it. To such an one we speak as those who are like us have spoken to us, and have so become our comfort in the wilderness of this life. Meanwhile the object is pursued on its own account and for its own sake. Now it happens curiously enough with philosophical meditations, that precisely that which one has thought out and investigated for oneself, is afterwards of benefit to others; not that, however, which was originally intended for others. The former is confessedly nearest in character to perfect honesty; for a man does not seek to deceive himself, nor does he offer himself empty husks; so that all sophistication and all mere talk is omitted, and consequently every sentence that is written at once repays the trouble of reading it. Thus my writings bear the stamp of honesty and openness so distinctly on the face of them, that by this alone they are a glaring contrast to those of three celebrated sophists of the post-Kantian period. I am always to be found at the standpoint of reflection, i.e., rational deliberation and honest statement, never at that of inspiration, called intellectual intuition, or absolute thought; though, if it received its proper name, it would be called empty bombast and charlatanism. Working then in this spirit, and always seeing the false and bad in universal acceptance, yea, bombast[3] and charlatanism[4] in the highest honour, I have long renounced the approbation of my contemporaries. It is impossible that an age which for twenty years has applauded a Hegel, that intellectual Caliban, as the greatest of the philosophers, so loudly that it echoes through the whole of Europe, could make him who has looked on at that desirous of its approbation. It has no more crowns of honour to bestow; its applause is prostituted, and its censure has no significance. That I mean what I say is attested by the fact that if I had in any way sought the approbation of my contemporaries, I would have had to strike out a score of passages which entirely contradict all their opinions, and indeed must in part be offensive to them. But I would count it a crime to sacrifice a single syllable to that approbation. My guiding star has, in all seriousness, been truth. Following it, I could first aspire only to my own approbation, entirely averted from an age deeply degraded as regards all higher intellectual efforts, and a national literature demoralised even to the exceptions, a literature in which the art of combining lofty words with paltry significance has reached its height. I can certainly never escape from the errors and weaknesses which, in my case as in every one else’s, necessarily belong to my nature; but I will not increase them by unworthy accommodations.

As regards this second edition, first of all I am glad to say that after five and twenty years I find nothing to retract; so that my fundamental convictions have only been confirmed, as far as concerns myself at least. The alterations in the first volume therefore, which contains the whole text of the first edition, nowhere touch what is essential. Sometimes they concern things of merely secondary importance, and more often consist of very short explanatory additions inserted here and there. Only the criticism of the Kantian philosophy has received important corrections and large additions, for these could not be put into a supplementary book, such as those which are given in the second volume, and which correspond to each of the four books that contain the exposition of my own doctrine. In the case of the latter, I have chosen this form of enlarging and improving them, because the five and twenty years that have passed since they were composed have produced so marked a change in my method of exposition and in my style, that it would not have done to combine the content of the second volume with that of the first, as both must have suffered by the fusion. I therefore give both works separately, and in the earlier exposition, even in many places where I would now express myself quite differently, I have changed nothing, because I desired to guard against spoiling the work of my earlier years through the carping criticism of age. What in this regard might need correction will correct itself in the mind of the reader with the help of the second volume. Both volumes have, in the full sense of the word, a supplementary relation to each other, so far as this rests on the fact that one age of human life is, intellectually, the supplement of another. It will therefore be found, not only that each volume contains what the other lacks, but that the merits of the one consist peculiarly in that which is wanting in the other. Thus, if the first half of my work surpasses the second in what can only be supplied by the fire of youth and the energy of first conceptions, the second will surpass the first by the ripeness and complete elaboration of the thought which can only belong to the fruit of the labour of a long life. For when I had the strength originally to grasp the fundamental thought of my system, to follow it at once into its four branches, to return from them to the unity of their origin, and then to explain the whole distinctly, I could not yet be in a position to work out all the branches of the system with the fulness, thoroughness, and elaborateness which is only reached by the meditation of many years—meditation which is required to test and illustrate the system by innumerable facts, to support it by the most different kinds of proof, to throw light on it from all sides, and then to place the different points of view boldly in contrast, to separate thoroughly the multifarious materials, and present them in a well-arranged whole. Therefore, although it would, no doubt, have been more agreeable to the reader to have my whole work in one piece, instead of consisting, as it now does, of two halves, which must be combined in using them, he must reflect that this would have demanded that I should accomplish at one period of life what it is only possible to accomplish in two, for I would have had to possess the qualities at one period of life that nature has divided between two quite different ones. Hence the necessity of presenting my work in two halves supplementary to each other may be compared to the necessity in consequence of which a chromatic object-glass, which cannot be made out of one piece, is produced by joining together a convex lens of flint glass and a concave lens of crown glass, the combined effect of which is what was sought. Yet, on the other hand, the reader will find some compensation for the inconvenience of using two volumes at once, in the variety and the relief which is afforded by the handling of the same subject, by the same mind, in the same spirit, but in very different years. However, it is very advisable that those who are not yet acquainted with my philosophy should first of all read the first volume without using the supplementary books, and should make use of these only on a second perusal; otherwise it would be too difficult for them to grasp the system in its connection. For it is only thus explained in the first volume, while the second is devoted to a more detailed investigation and a complete development of the individual doctrines. Even those who should not make up their minds to a second reading of the first volume had better not read the second volume till after the first, and then for itself, in the ordinary sequence of its chapters, which, at any rate, stand in some kind of connection, though a somewhat looser one, the gaps of which they will fully supply by the recollection of the first volume, if they have thoroughly comprehended it. Besides, they will find everywhere the reference to the corresponding passages of the first volume, the paragraphs of which I have numbered in the second edition for this purpose, though in the first edition they were only divided by lines.

I have already explained in the preface to the first edition, that my philosophy is founded on that of Kant, and therefore presupposes a thorough knowledge of it. I repeat this here. For Kant’s teaching produces in the mind of every one who has comprehended it a fundamental change which is so great that it may be regarded as an intellectual new-birth. It alone is able really to remove the inborn realism which proceeds from the original character of the intellect, which neither Berkeley nor Malebranche succeed in doing, for they remain too much in the universal, while Kant goes into the particular, and indeed in a way that is quite unexampled both before and after him, and which has quite a peculiar, and, we might say, immediate effect upon the mind in consequence of which it undergoes a complete undeception, and forthwith looks at all things in another light. Only in this way can any one become susceptible to the more positive expositions which I have to give. On the other hand, he who has not mastered the Kantian philosophy, whatever else he may have studied, is, as it were, in a state of innocence; that is to say, he remains in the grasp of that natural and childish realism in which we are all born, and which fits us for everything possible, with the single exception of philosophy. Such a man then stands to the man who knows the Kantian philosophy as a minor to a man of full age. That this truth should nowadays sound paradoxical, which would not have been the case in the first thirty years after the appearance of the Critique of Reason, is due to the fact that a generation has grown up that does not know Kant properly, because it has never heard more of him than a hasty, impatient lecture, or an account at second-hand; and this again is due to the fact that in consequence of bad guidance, this generation has wasted its time with the philosophemes of vulgar, uncalled men, or even of bombastic sophists, which are unwarrantably commended to it. Hence the confusion of fundamental conceptions, and in general the unspeakable crudeness and awkwardness that appears from under the covering of affectation and pretentiousness in the philosophical attempts of the generation thus brought up. But whoever thinks he can learn Kant’s philosophy from the exposition of others makes a terrible mistake. Nay, rather I must earnestly warn against such accounts, especially the more recent ones; and indeed in the years just past I have met with expositions of the Kantian philosophy in the writings of the Hegelians which actually reach the incredible. How should the minds that in the freshness of youth have been strained and ruined by the nonsense of Hegelism, be still capable of following Kant’s profound investigations? They are early accustomed to take the hollowest jingle of words for philosophical thoughts, the most miserable sophisms for acuteness, and silly conceits for dialectic, and their minds are disorganised through the admission of mad combinations of words to which the mind torments and exhausts itself in vain to attach some thought. No Critique of Reason can avail them, no philosophy, they need a medicina mentis, first as a sort of purgative, un petit cours de senscommunologie, and then one must further see whether, in their case, there can even be any talk of philosophy. The Kantian doctrine then will be sought for in vain anywhere else but in Kant’s own works; but these are throughout instructive, even where he errs, even where he fails. In consequence of his originality, it holds good of him in the highest degree, as indeed of all true philosophers, that one can only come to know them from their own works, not from the accounts of others. For the thoughts of any extraordinary intellect cannot stand being filtered through the vulgar mind. Born behind the broad, high, finely-arched brow, from under which shine beaming eyes, they lose all power and life, and appear no longer like themselves, when removed to the narrow lodging and low roofing of the confined, contracted, thick-walled skull from which dull glances steal directed to personal ends. Indeed we may say that minds of this kind act like an uneven glass, in which everything is twisted and distorted, loses the regularity of its beauty, and becomes a caricature. Only from their authors themselves can we receive philosophical thoughts; therefore whoever feels himself drawn to philosophy must himself seek out its immortal teachers in the still sanctuary of their works. The principal chapters of any one of these true philosophers will afford a thousand times more insight into their doctrines than the heavy and distorted accounts of them that everyday men produce, who are still for the most part deeply entangled in the fashionable philosophy of the time, or in the sentiments of their own minds. But it is astonishing how decidedly the public seizes by preference on these expositions at second-hand. It seems really as if elective affinities were at work here, by virtue of which the common nature is drawn to its like, and therefore will rather hear what a great man has said from one of its own kind. Perhaps this rests on the same principle as that of mutual instruction, according to which children learn best from children.

************************************

One word more for the professors of philosophy. I have always been compelled to admire not merely the sagacity, the true and fine tact with which, immediately on its appearance, they recognised my philosophy as something altogether different from and indeed dangerous to their own attempts, or, in popular language, something that would not suit their turn; but also the sure and astute policy by virtue of which they at once discovered the proper procedure with regard to it, the complete harmony with which they applied it, and the persistency with which they have remained faithful to it. This procedure, which further commended itself by the great ease of carrying it out, consists, as is well known, in altogether ignoring and thus in secreting—according to Goethe’s malicious phrase, which just means the appropriating of what is of weight and significance. The efficiency of this quiet means is increased by the Corybantic shouts with which those who are at one reciprocally greet the birth of their own spiritual children—shouts which compel the public to look and note the air of importance with which they congratulate themselves on the event. Who can mistake the object of such proceedings? Is there then nothing to oppose to the maxim, primum vivere, deinde philosophari? These gentlemen desire to live, and indeed to live by philosophy. To philosophy they are assigned with their wives and children, and in spite of Petrarch’s povera e nuda vai filosofia, they have staked everything upon it. Now my philosophy is by no means so constituted that any one can live by it. It lacks the first indispensable requisite of a well-paid professional philosophy, a speculative theology, which—in spite of the troublesome Kant with his Critique of Reason—should and must, it is supposed, be the chief theme of all philosophy, even if it thus takes on itself the task of talking straight on of that of which it can know absolutely nothing. Indeed my philosophy does not permit to the professors the fiction they have so cunningly devised, and which has become so indispensable to them, of a reason that knows, perceives, or apprehends immediately and absolutely. This is a doctrine which it is only necessary to impose upon the reader at starting, in order to pass in the most comfortable manner in the world, as it were in a chariot and four, into that region beyond the possibility of all experience, which Kant has wholly and for ever shut out from our knowledge, and in which are found immediately revealed and most beautifully arranged the fundamental dogmas of modern, Judaising, optimistic Christianity. Now what in the world has my subtle philosophy, deficient as it is in these essential requisites, with no intentional aim, and unable to afford a means of subsistence, whose pole star is truth alone the naked, unrewarded, unbefriended, often persecuted truth, and which steers straight for it without looking to the right hand or the left,—what, I say, has this to do with that alma mater, the good, well-to-do university philosophy which, burdened with a hundred aims and a thousand motives, comes on its course cautiously tacking, while it keeps before its eyes at all times the fear of the Lord, the will of the ministry, the laws of the established church, the wishes of the publisher, the attendance of the students, the goodwill of colleagues, the course of current politics, the momentary tendency of the public, and Heaven knows what besides? Or what has my quiet, earnest search for truth in common with the noisy scholastic disputations of the chair and the benches, the inmost motives of which are always personal aims. The two kinds of philosophy are, indeed, radically different. Thus it is that with me there is no compromise and no fellowship, that no one reaps any benefit from my works but the man who seeks the truth alone, and therefore none of the philosophical parties of the day; for they all follow their own aims, while I have only insight into truth to offer, which suits none of these aims, because it is not modelled after any of them. If my philosophy is to become susceptible of professorial exposition, the times must entirely change. What a pretty thing it would be if a philosophy by which nobody could live were to gain for itself light and air, not to speak of the general ear! This must be guarded against, and all must oppose it as one man. But it is not just such an easy game to controvert and refute; and, moreover, these are mistaken means to employ, because they just direct the attention of the public to the matter, and its taste for the lucubrations of the professors of philosophy might be destroyed by the perusal of my writings. For whoever has tasted of earnest will not relish jest, especially when it is tiresome. Therefore the silent system, so unanimously adopted, is the only right one, and I can only advise them to stick to it and go on with it as long as it will answer, that is, until to ignore is taken to imply ignorance; then there will just be time to turn back. Meanwhile it remains open to every one to pluck out a small feather here and there for his own use, for the superfluity of thoughts at home should not be very oppressive. Thus the ignoring and silent system may hold out a good while, at least the span of time I may have yet to live, whereby much is already won. And if, in the meantime, here and there an indiscreet voice has let itself be heard, it is soon drowned by the loud talking of the professors, who, with important airs, know how to entertain the public with very different things. I advise, however, that the unanimity of procedure should be somewhat more strictly observed, and especially that the young men should be looked after, for they are sometimes so fearfully indiscreet. For even so I cannot guarantee that the commended procedure will last for ever, and cannot answer for the final issue. It is a nice question as to the steering of the public, which, on the whole, is good and tractable. Although we nearly at all times see the Gorgiases and the Hippiases uppermost, although the absurd, as a rule, predominates, and it seems impossible that the voice of the individual can ever penetrate through the chorus of the befooling and the befooled, there yet remains to the genuine works of every age a quite peculiar, silent, slow, and powerful influence; and, as if by a miracle, we see them rise at last out of the turmoil like a balloon that floats up out of the thick atmosphere of this globe into purer regions, where, having once arrived, it remains at rest, and no one can draw it down again.

Written at Frankfort-on-the-Maine in February 1844.

First Book. The World As Idea

First Aspect. The Idea Subordinated To The Principle Of Sufficient Reason: The Object Of Experience And Science

Sors de l’enfance, ami réveille toi!

—Jean Jacques Rousseau.

§ 1. ”The world is my idea:”—this is a truth which holds good for everything that lives and knows, though man alone can bring it into reflective and abstract consciousness. If he really does this, he has attained to philosophical wisdom. It then becomes clear and certain to him that what he knows is not a sun and an earth, but only an eye that sees a sun, a hand that feels an earth; that the world which surrounds him is there only as idea, i.e., only in relation to something else, the consciousness, which is himself. If any truth can be asserted a priori, it is this: for it is the expression of the most general form of all possible and thinkable experience: a form which is more general than time, or space, or causality, for they all presuppose it; and each of these, which we have seen to be just so many modes of the principle of sufficient reason, is valid only for a particular class of ideas; whereas the antithesis of object and subject is the common form of all these classes, is that form under which alone any idea of whatever kind it may be, abstract or intuitive, pure or empirical, is possible and thinkable. No truth therefore is more certain, more independent of all others, and less in need of proof than this, that all that exists for knowledge, and therefore this whole world, is only object in relation to subject, perception of a perceiver, in a word, idea. This is obviously true of the past and the future, as well as of the present, of what is farthest off, as of what is near; for it is true of time and space themselves, in which alone these distinctions arise. All that in any way belongs or can belong to the world is inevitably thus conditioned through the subject, and exists only for the subject. The world is idea.

This truth is by no means new. It was implicitly involved in the sceptical reflections from which Descartes started. Berkeley, however, was the first who distinctly enunciated it, and by this he has rendered a permanent service to philosophy, even though the rest of his teaching should not endure. Kant’s primary mistake was the neglect of this principle, as is shown in the appendix. How early again this truth was recognised by the wise men of India, appearing indeed as the fundamental tenet of the Vedânta philosophy ascribed to Vyasa, is pointed out by Sir William Jones in the last of his essays: ”On the philosophy of the Asiatics” (Asiatic Researches, vol. iv. p. 164), where he says, ”The fundamental tenet of the Vedanta school consisted not in denying the existence of matter, that is, of solidity, impenetrability, and extended figure (to deny which would be lunacy), but in correcting the popular notion of it, and in contending that it has no essence independent of mental perception; that existence and perceptibility are convertible terms.” These words adequately express the compatibility of empirical reality and transcendental ideality.

In this first book, then, we consider the world only from this side, only so far as it is idea. The inward reluctance with which any one accepts the world as merely his idea, warns him that this view of it, however true it may be, is nevertheless one-sided, adopted in consequence of some arbitrary abstraction. And yet it is a conception from which he can never free himself. The defectiveness of this view will be corrected in the next book by means of a truth which is not so immediately certain as that from which we start here; a truth at which we can arrive only by deeper research and more severe abstraction, by the separation of what is different and the union of what is identical. This truth, which must be very serious and impressive if not awful to every one, is that a man can also say and must say, ”the world is my will.”

In this book, however, we must consider separately that aspect of the world from which we start, its aspect as knowable, and therefore, in the meantime, we must, without reserve, regard all presented objects, even our own bodies (as we shall presently show more fully), merely as ideas, and call them merely ideas. By so doing we always abstract from will (as we hope to make clear to every one further on), which by itself constitutes the other aspect of the world. For as the world is in one aspect entirely idea, so in another it is entirely will. A reality which is neither of these two, but an object in itself (into which the thing in itself has unfortunately dwindled in the hands of Kant), is the phantom of a dream, and its acceptance is an ignis fatuus in philosophy.

§ 2. That which knows all things and is known by none is the subject. Thus it is the supporter of the world, that condition of all phenomena, of all objects which is always pre-supposed throughout experience; for all that exists, exists only for the subject. Every one finds himself to be subject, yet only in so far as he knows, not in so far as he is an object of knowledge. But his body is object, and therefore from this point of view we call it idea. For the body is an object among objects, and is conditioned by the laws of objects, although it is an immediate object. Like all objects of perception, it lies within the universal forms of knowledge, time and space, which are the conditions of multiplicity. The subject, on the contrary, which is always the knower, never the known, does not come under these forms, but is presupposed by them; it has therefore neither multiplicity nor its opposite unity. We never know it, but it is always the knower wherever there is knowledge.

So then the world as idea, the only aspect in which we consider it at present, has two fundamental, necessary, and inseparable halves. The one half is the object, the forms of which are space and time, and through these multiplicity. The other half is the subject, which is not in space and time, for it is present, entire and undivided, in every percipient being. So that any one percipient being, with the object, constitutes the whole world as idea just as fully as the existing millions could do; but if this one were to disappear, then the whole world as idea would cease to be. These halves are therefore inseparable even for thought, for each of the two has meaning and existence only through and for the other, each appears with the other and vanishes with it. They limit each other immediately; where the object begins the subject ends. The universality of this limitation is shown by the fact that the essential and hence universal forms of all objects, space, time, and causality, may, without knowledge of the object, be discovered and fully known from a consideration of the subject, i.e., in Kantian language, they lie a priori in our consciousness. That he discovered this is one of Kant’s principal merits, and it is a great one. I however go beyond this, and maintain that the principle of sufficient reason is the general expression for all these forms of the object of which we are a priori conscious; and that therefore all that we know purely a priori, is merely the content of that principle and what follows from it; in it all our certain a priori knowledge is expressed. In my essay on the principle of sufficient reason I have shown in detail how every possible object comes under it; that is, stands in a necessary relation to other objects, on the one side as determined, on the other side as determining: this is of such wide application, that the whole existence of all objects, so far as they are objects, ideas and nothing more, may be entirely traced to this their necessary relation to each other, rests only in it, is in fact merely relative; but of this more presently. I have further shown, that the necessary relation which the principle of sufficient reason expresses generally, appears in other forms corresponding to the classes into which objects are divided, according to their possibility; and again that by these forms the proper division of the classes is tested. I take it for granted that what I said in this earlier essay is known and present to the reader, for if it had not been already said it would necessarily find its place here.

§ 3. The chief distinction among our ideas is that between ideas of perception and abstract ideas. The latter form just one class of ideas, namely concepts, and these are the possession of man alone of all creatures upon earth. The capacity for these, which distinguishes him from all the lower animals, has always been called reason.[5] We shall consider these abstract ideas by themselves later, but, in the first place, we shall speak exclusively of the ideas of perception. These comprehend the whole visible world, or the sum total of experience, with the conditions of its possibility. We have already observed that it is a highly important discovery of Kant’s, that these very conditions, these forms of the visible world, i.e., the absolutely universal element in its perception, the common property of all its phenomena, space and time, even when taken by themselves and apart from their content, can, not only be thought in the abstract, but also be directly perceived; and that this perception or intuition is not some kind of phantasm arising from constant recurrence in experience, but is so entirely independent of experience that we must rather regard the latter as dependent on it, inasmuch as the qualities of space and time, as they are known in a priori perception or intuition, are valid for all possible experience, as rules to which it must invariably conform. Accordingly, in my essay on the principle of sufficient reason, I have treated space and time, because they are perceived as pure and empty of content, as a special and independent class of ideas. This quality of the universal forms of intuition, which was discovered by Kant, that they may be perceived in themselves and apart from experience, and that they may be known as exhibiting those laws on which is founded the infallible science of mathematics, is certainly very important. Not less worthy of remark, however, is this other quality of time and space, that the principle of sufficient reason, which conditions experience as the law of causation and of motive, and thought as the law of the basis of judgment, appears here in quite a special form, to which I have given the name of the ground of being. In time, this is the succession of its moments, and in space the position of its parts, which reciprocally determine each other ad infinitum.

Any one who has fully understood from the introductory essay the complete identity of the content of the principle of sufficient reason in all its different forms, must also be convinced of the importance of the knowledge of the simplest of these forms, as affording him insight into his own inmost nature. This simplest form of the principle we have found to be time. In it each instant is, only in so far as it has effaced the preceding one, its generator, to be itself in turn as quickly effaced. The past and the future (considered apart from the consequences of their content) are empty as a dream, and the present is only the indivisible and unenduring boundary between them. And in all the other forms of the principle of sufficient reason, we shall find the same emptiness, and shall see that not time only but also space, and the whole content of both of them, i.e., all that proceeds from causes and motives, has a merely relative existence, is only through and for another like to itself, i.e., not more enduring. The substance of this doctrine is old: it appears in Heraclitus when he laments the eternal flux of things; in Plato when he degrades the object to that which is ever becoming, but never being; in Spinoza as the doctrine of the mere accidents of the one substance which is and endures. Kant opposes what is thus known as the mere phenomenon to the thing in itself. Lastly, the ancient wisdom of the Indian philosophers declares, ”It is Mâyâ, the veil of deception, which blinds the eyes of mortals, and makes them behold a world of which they cannot say either that it is or that it is not: for it is like a dream; it is like the sunshine on the sand which the traveller takes from afar for water, or the stray piece of rope he mistakes for a snake.” (These similes are repeated in innumerable passages of the Vedas and the Puranas.) But what all these mean, and that of which they all speak, is nothing more than what we have just considered—the world as idea subject to the principle of sufficient reason.

§ 4. Whoever has recognised the form of the principle of sufficient reason, which appears in pure time as such, and on which all counting and arithmetical calculation rests, has completely mastered the nature of time. Time is nothing more than that form of the principle of sufficient reason, and has no further significance. Succession is the form of the principle of sufficient reason in time, and succession is the whole nature of time. Further, whoever has recognised the principle of sufficient reason as it appears in the presentation of pure space, has exhausted the whole nature of space, which is absolutely nothing more than that possibility of the reciprocal determination of its parts by each other, which is called position. The detailed treatment of this, and the formulation in abstract conceptions of the results which flow from it, so that they may be more conveniently used, is the subject of the science of geometry. Thus also, whoever has recognised the law of causation, the aspect of the principle of sufficient reason which appears in what fills these forms (space and time) as objects of perception, that is to say matter, has completely mastered the nature of matter as such, for matter is nothing more than causation, as any one will see at once if he reflects. Its true being is its action, nor can we possibly conceive it as having any other meaning. Only as active does it fill space and time; its action upon the immediate object (which is itself matter) determines that perception in which alone it exists. The consequence of the action of any material object upon any other, is known only in so far as the latter acts upon the immediate object in a different way from that in which it acted before; it consists only of this. Cause and effect thus constitute the whole nature of matter; its true being is its action. (A fuller treatment of this will be found in the essay on the Principle of Sufficient Reason, § 21, p. 77.) The nature of all material things is therefore very appropriately called in German Wirklichkeit,[6] a word which is far more expressive than Realität. Again, that which is acted upon is always matter, and thus the whole being and essence of matter consists in the orderly change, which one part of it brings about in another part. The existence of matter is therefore entirely relative, according to a relation which is valid only within its limits, as in the case of time and space.

But time and space, each for itself, can be mentally presented apart from matter, whereas matter cannot be so presented apart from time and space. The form which is inseparable from it presupposes space, and the action in which its very existence consists, always imports some change, in other words a determination in time. But space and time are not only, each for itself, presupposed by matter, but a union of the two constitutes its essence, for this, as we have seen, consists in action, i.e., in causation. All the innumerable conceivable phenomena and conditions of things, might be coexistent in boundless space, without limiting each other, or might be successive in endless time without interfering with each other: thus a necessary relation of these phenomena to each other, and a law which should regulate them according to such a relation, is by no means needful, would not, indeed, be applicable: it therefore follows that in the case of all co-existence in space and change in time, so long as each of these forms preserves for itself its condition and its course without any connection with the other, there can be no causation, and since causation constitutes the essential nature of matter, there can be no matter. But the law of causation receives its meaning and necessity only from this, that the essence of change does not consist simply in the mere variation of things, but rather in the fact that at the same part of space there is now one thing and then another, and at one and the same point of time there is here one thing and there another: only this reciprocal limitation of space and time by each other gives meaning, and at the same time necessity, to a law, according to which change must take place. What is determined by the law of causality is therefore not merely a succession of things in time, but this succession with reference to a definite space, and not merely existence of things in a particular place, but in this place at a different point of time. Change, i.e., variation which takes place according to the law of causality, implies always a determined part of space and a determined part of time together and in union. Thus causality unites space with time. But we found that the whole essence of matter consisted in action, i.e., in causation, consequently space and time must also be united in matter, that is to say, matter must take to itself at once the distinguishing qualities both of space and time, however much these may be opposed to each other, and must unite in itself what is impossible for each of these independently, that is, the fleeting course of time, with the rigid unchangeable perduration of space: infinite divisibility it receives from both. It is for this reason that we find that co-existence, which could neither be in time alone, for time has no contiguity, nor in space alone, for space has no before, after, or now, is first established through matter. But the co-existence of many things constitutes, in fact, the essence of reality, for through it permanence first becomes possible; for permanence is only knowable in the change of something which is present along with what is permanent, while on the other hand it is only because something permanent is present along with what changes, that the latter gains the special character of change, i.e., the mutation of quality and form in the permanence of substance, that is to say, in matter.[7] If the world were in space alone, it would be rigid and immovable, without succession, without change, without action; but we know that with action, the idea of matter first appears. Again, if the world were in time alone, all would be fleeting, without persistence, without contiguity, hence without co-existence, and consequently without permanence; so that in this case also there would be no matter. Only through the union of space and time do we reach matter, and matter is the possibility of co-existence, and, through that, of permanence; through permanence again matter is the possibility of the persistence of substance in the change of its states.[8] As matter consists in the union of space and time, it bears throughout the stamp of both. It manifests its origin in space, partly through the form which is inseparable from it, but especially through its persistence (substance), the a priori certainty of which is therefore wholly deducible from that of space[9] (for variation belongs to time alone, but in it alone and for itself nothing is persistent). Matter shows that it springs from time by quality (accidents), without which it never exists, and which is plainly always causality, action upon other matter, and therefore change (a time concept). The law of this action, however, always depends upon space and time together, and only thus obtains meaning. The regulative function of causality is confined entirely to the determination of what must occupy this time and this space. The fact that we know a priori the unalterable characteristics of matter, depends upon this derivation of its essential nature from the forms of our knowledge of which we are conscious a priori. These unalterable characteristics are space-occupation, i.e., impenetrability, i.e., causal action, consequently, extension, infinite divisibility, persistence, i.e., indestructibility, and lastly mobility: weight, on the other hand, notwithstanding its universality, must be attributed to a posteriori knowledge, although Kant, in his ”Metaphysical Introduction to Natural Philosophy,” p. 71 (p. 372 of Rosenkranz’s edition), treats it as knowable a priori.

But as the object in general is only for the subject, as its idea, so every special class of ideas is only for an equally special quality in the subject, which is called a faculty of perception. This subjective correlative of time and space in themselves as empty forms, has been named by Kant pure sensibility; and we may retain this expression, as Kant was the first to treat of the subject, though it is not exact, for sensibility presupposes matter. The subjective correlative of matter or of causation, for these two are the same, is understanding, which is nothing more than this. To know causality is its one function, its only power; and it is a great one, embracing much, of manifold application, yet of unmistakable identity in all its manifestations. Conversely all causation, that is to say, all matter, or the whole of reality, is only for the understanding, through the understanding, and in the understanding. The first, simplest, and ever-present example of understanding is the perception of the actual world. This is throughout knowledge of the cause from the effect, and therefore all perception is intellectual. The understanding could never arrive at this perception, however, if some effect did not become known immediately, and thus serve as a starting-point. But this is the affection of the animal body. So far, then, the animal body is the immediate object of the subject; the perception of all other objects becomes possible through it. The changes which every animal body experiences, are immediately known, that is, felt; and as these effects are at once referred to their causes, the perception of the latter as objects arises. This relation is no conclusion in abstract conceptions; it does not arise from reflection, nor is it arbitrary, but immediate, necessary, and certain. It is the method of knowing of the pure understanding, without which there could be no perception; there would only remain a dull plant-like consciousness of the changes of the immediate object, which would succeed each other in an utterly unmeaning way, except in so far as they might have a meaning for the will either as pain or pleasure. But as with the rising of the sun the visible world appears, so at one stroke, the understanding, by means of its one simple function, changes the dull, meaningless sensation into perception. What the eye, the ear, or the hand feels, is not perception; it is merely its data. By the understanding passing from the effect to the cause, the world first appears as perception extended in space, varying in respect of form, persistent through all time in respect of matter; for the understanding unites space and time in the idea of matter, that is, causal action. As the world as idea exists only through the understanding, so also it exists only for the understanding. In the first chapter of my essay on ”Light and Colour,” I have already explained how the understanding constructs perceptions out of the data supplied by the senses; how by comparison of the impressions which the various senses receive from the object, a child arrives at perceptions; how this alone affords the solution of so many phenomena of the senses; the single vision of two eyes, the double vision in the case of a squint, or when we try to look at once at objects which lie at unequal distances behind each other; and all illusion which is produced by a sudden alteration in the organs of sense. But I have treated this important subject much more fully and thoroughly in the second edition of the essay on ”The Principle of Sufficient Reason,” § 21. All that is said there would find its proper place here, and would therefore have to be said again; but as I have almost as much disinclination to quote myself as to quote others, and as I am unable to explain the subject better than it is explained there, I refer the reader to it, instead of quoting it, and take for granted that it is known.

The process by which children, and persons born blind who have been operated upon, learn to see, the single vision of the double sensation of two eyes, the double vision and double touch which occur when the organs of sense have been displaced from their usual position, the upright appearance of objects while the picture on the retina is upside down, the attributing of colour to the outward objects, whereas it is merely an inner function, a division through polarisation, of the activity of the eye, and lastly the stereoscope,—all these are sure and incontrovertible evidence that perception is not merely of the senses, but intellectual—that is, pure knowledge through the understanding of the cause from the effect, and that, consequently, it presupposes the law of causality, in a knowledge of which all perception—that is to say all experience, by virtue of its primary and only possibility, depends. The contrary doctrine that the law of causality results from experience, which was the scepticism of Hume, is first refuted by this. For the independence of the knowledge of causality of all experience,—that is, its a priori character—can only be deduced from the dependence of all experience upon it; and this deduction can only be accomplished by proving, in the manner here indicated, and explained in the passages referred to above, that the knowledge of causality is included in perception in general, to which all experience belongs, and therefore in respect of experience is completely a priori, does not presuppose it, but is presupposed by it as a condition. This, however, cannot be deduced in the manner attempted by Kant, which I have criticised in the essay on ”The Principle of Sufficient Reason,” § 23.

§ 5. It is needful to guard against the grave error of supposing that because perception arises through the knowledge of causality, the relation of subject and object is that of cause and effect. For this relation subsists only between the immediate object and objects known indirectly, thus always between objects alone. It is this false supposition that has given rise to the foolish controversy about the reality of the outer world; a controversy in which dogmatism and scepticism oppose each other, and the former appears, now as realism, now as idealism. Realism treats the object as cause, and the subject as its effect. The idealism of Fichte reduces the object to the effect of the subject. Since however, and this cannot be too much emphasised, there is absolutely no relation according to the principle of sufficient reason between subject and object, neither of these views could be proved, and therefore scepticism attacked them both with success. Now, just as the law of causality precedes perception and experience as their condition, and therefore cannot (as Hume thought) be derived from them, so object and subject precede all knowledge, and hence the principle of sufficient reason in general, as its first condition; for this principle is merely the form of all objects, the whole nature and possibility of their existence as phenomena: but the object always presupposes the subject; and therefore between these two there can be no relation of reason and consequent. My essay on the principle of sufficient reason accomplishes just this: it explains the content of that principle as the essential form of every object—that is to say, as the universal nature of all objective existence, as something which pertains to the object as such; but the object as such always presupposes the subject as its necessary correlative; and therefore the subject remains always outside the province in which the principle of sufficient reason is valid. The controversy as to the reality of the outer world rests upon this false extension of the validity of the principle of sufficient reason to the subject also, and starting with this mistake it can never understand itself. On the one side realistic dogmatism, looking upon the idea as the effect of the object, desires to separate these two, idea and object, which are really one, and to assume a cause quite different from the idea, an object in itself, independent of the subject, a thing which is quite inconceivable; for even as object it presupposes subject, and so remains its idea. Opposed to this doctrine is scepticism, which makes the same false presupposition that in the idea we have only the effect, never the cause, therefore never real being; that we always know merely the action of the object. But this object, it supposes, may perhaps have no resemblance whatever to its effect, may indeed have been quite erroneously received as the cause, for the law of causality is first to be gathered from experience, and the reality of experience is then made to rest upon it. Thus both of these views are open to the correction, firstly, that object and idea are the same; secondly, that the true being of the object of perception is its action, that the reality of the thing consists in this, and the demand for an existence of the object outside the idea of the subject, and also for an essence of the actual thing different from its action, has absolutely no meaning, and is a contradiction: and that the knowledge of the nature of the effect of any perceived object, exhausts such an object itself, so far as it is object, i.e., idea, for beyond this there is nothing more to be known. So far then, the perceived world in space and time, which makes itself known as causation alone, is entirely real, and is throughout simply what it appears to be, and it appears wholly and without reserve as idea, bound together according to the law of causality. This is its empirical reality. On the other hand, all causality is in the understanding alone, and for the understanding. The whole actual, that is, active world is determined as such through the understanding, and apart from it is nothing. This, however, is not the only reason for altogether denying such a reality of the outer world as is taught by the dogmatist, who explains its reality as its independence of the subject. We also deny it, because no object apart from a subject can be conceived without contradiction. The whole world of objects is and remains idea, and therefore wholly and for ever determined by the subject; that is to say, it has transcendental ideality. But it is not therefore illusion or mere appearance; it presents itself as that which it is, idea, and indeed as a series of ideas of which the common bond is the principle of sufficient reason. It is according to its inmost meaning quite comprehensible to the healthy understanding, and speaks a language quite intelligible to it. To dispute about its reality can only occur to a mind perverted by over-subtilty, and such discussion always arises from a false application of the principle of sufficient reason, which binds all ideas together of whatever kind they may be, but by no means connects them with the subject, nor yet with a something which is neither subject nor object, but only the ground of the object; an absurdity, for only objects can be and always are the ground of objects. If we examine more closely the source of this question as to the reality of the outer world, we find that besides the false application of the principle of sufficient reason generally to what lies beyond its province, a special confusion of its forms is also involved; for that form which it has only in reference to concepts or abstract ideas, is applied to perceived ideas, real objects; and a ground of knowing is demanded of objects, whereas they can have nothing but a ground of being. Among the abstract ideas, the concepts united in the judgment, the principle of sufficient reason appears in such a way that each of these has its worth, its validity, and its whole existence, here called truth, simply and solely through the relation of the judgment to something outside of it, its ground of knowledge, to which there must consequently always be a return. Among real objects, ideas of perception, on the other hand, the principle of sufficient reason appears not as the principle of the ground of knowing, but of being, as the law of causality: every real object has paid its debt to it, inasmuch as it has come to be, i.e., has appeared as the effect of a cause. The demand for a ground of knowing has therefore here no application and no meaning, but belongs to quite another class of things. Thus the world of perception raises in the observer no question or doubt so long as he remains in contact with it: there is here neither error nor truth, for these are confined to the province of the abstract—the province of reflection. But here the world lies open for sense and understanding; presents itself with naive truth as that which it really is—ideas of perception which develop themselves according to the law of causality.