Greek Popular Religion

Martin P. Nilsson

First published in 1940.

This online edition was created and published by Global Grey on the 2nd February 2023.

Table of Contents

Legalism And Superstition; Hell

Foreword

Late in the last century the American committee for Lectures on the History of Religions came into existence. It was established to cooperate with colleges and seminaries over the United States in providing courses of lectures to be delivered at various centers and to publish the lectures. All the lectures, except those of Professor Paul Pelliot on “Religions in Central Asia” in 1923 and those of Professor A. V. Williams Jackson on “The Religion of Persia” in 1907-8, were published as the “American Lectures on the History of Religions.” They formed an important series of volumes, the titles of which are:

T. W. Rhys Davids, Buddhism (1896)

Daniel G. Brinton, Religions of Primitive Peoples (1897)

T. K. Cheyne, Jewish Religious Life after the Exile (1898)

Karl Budde, Religion of Israel to the Exile (1899)

Georg Steindorff, The Religion of the Ancient Egyptians (1905)

George W. Knox, The Development of Religion in Japan (1907)

Maurice Bloomfield, The Religion of the Veda (1908)

Morris Jastrow, Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria (1911)

J. J. M. de Groot, Religion in China (1912)

Franz Cumont, Astrology and Religion among the Greeks and Romans (1912)

C. Snouck Hurgronje, Mohammedanism (1916)

J. E. Carpenter, Phases of Early Christianity (1916)

The Committee was organized as a response to what was felt to be a general need. Professor C. H. Toy was the first chairman, and after him Professor Richard Gottheil, seconded by Professor Morris Jastrow, served in this capacity for many years.

In 1936 the members of the Committee turned over the funds and responsibilities to the American Council of Learned Societies, which appointed a Committee consisting of Dean Shirley Jackson Case and Professors C. H. Kraeling, James A. Montgomery, Herbert W. Schneider, and the writer. This is a revolving Committee: Dean Case, after his retirement from the Divinity School of the University of Chicago, was succeeded by Dean E. C. Colwell; and at the expiration of Professor Schneider’s term in July, 1940, Professor Arthur Jeffery took his place. The Committee enjoys the most helpful cooperation of the Institute of International Education in planning the journeys of its lecturers.

The Committee is fortunate in the first lecturer, Professor Martin P. Nilsson, who needs no introduction to the world of scholars. Starting as he did with the training of a philologist, proceeding to work as archaeologist and historian, and bringing to all that he handles an inborn understanding of folkways, he has made a series of fundamental contributions to our knowledge of ancient religion and primitive customs. In the extensive literature relating to ancient Greece, there is no work which serves the purposes of this volume.

The Committee wishes to express its thanks to Brown, California, Chicago, Cincinnati, Colorado, Columbia, Cornell, Harvard, Michigan, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and Stanford universities, to Kenyon, Mount Holyoke, Swarthmore, and Wellesley colleges, and to Meadville Theological School for generous participation in the scheme; to the Archaeological Institute of America for the third lecture, “The Religion of Eleusis,” which was delivered under the auspices of the Norton Lectureship and which, treating as it does the highest form of Greek popular religion, fits into and enriches this volume; and to the Columbia University Press for undertaking the publication of the series and for much editorial help-fulness.

To Mr. Emerson Buchanan, of the Columbia University Library, the Committee owes an especial debt for his careful revision of the entire manuscript. Professor Wendell T. Bush and Mrs. Marguerite Block, Curator of the Bush Collection of Religion and Culture, Columbia University, provided many of the illustrations.

If the new series serves sound learning in this field as its predecessor has done, the Committee will have great cause for happiness.

ARTHUR DARBY NOCK

For the Committee

Harvard University

Cambridge, Massachusetts

September, 1940

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment Is Hereby Made To: Alinari, Kaufmann, and the British Museum for the use of photographs; A. & C. Black, Ltd., for the figure from Dugas, Greek Pottery; F. Bruckmann, A.-G., for the figures from Brunn and Bruckmann, Denkmäler griechischer and römischer Sculptur, from Furtwängler and Reichhold, Griechische Vasenmalerei, and from the Festschrift für James Loeb zum sechzigsten Geburtstag gewidmet; Cambridge University Press for the figures from Cook, Zeus, and from Harrison, Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion; Gryphius-Verlag for the figure from Watzinger, Griechische Vasen in Tübingen; Libreria dello Stato for the figure from Rizzio, Monumenti della pittura antica scoperti in Italia; The Macmillan Company for the figures from Cook, Zeus, and from Dugas, Greek Pottery; Oxford University Press for the figures from Farnell, The Cults of the Greek States, and from Tod and Wace, A Catalogue of the Sparta Museum; Vereinigung wissenschaftlicher Verleger for the figure from Bieber, Die Denkmäler zum Theaterwesen im Altertum; Verlag der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften for the figure from Hiller von Gaertringen and Lattermann, Arkadische Forschungen; B. G. Teubner for the figure from Roscher, Ausführliches Lexikon der griechischen and römischen Mythologie; and the editors and directors of the Annual of the British School at Athens, Ephemeris archaiologike, Illustrated London News, Jahreshefte des Österreichischen archaologischen Institutes in Wien, and Mitteilungen des Deutschen archäologischen Institutsfor the use of other figures reproduced in this volume.

The Countryside

Greek religion in its various aspects has been the subject of numerous investigations. Modern research has progressed along two lines especially, the search for primitive survivals and the study of the literary expressions of religion. The first is attributable to the rise of the science of anthropology since the seventies of the last century. In this science the study of Greek religion, viewed as a direct development from a primitive nature religion, has always taken a prominent place. I need only mention the names of Andrew Lang, Sir James Frazer, and Jane Harrison. While it is true that there were very many relics of primitive religion in Greek religion, it must be remembered that Greece was a highly civilized country and that even its most backward inhabitants were subject to the influence of its culture. It is misleading, therefore, to represent Greek religion as essentially primitive. The primitive elements were modified and overlaid by higher elements through the development of Greek culture. They were survivals and must be treated as such.

The second line of research has been pursued by philologists, who, quite naturally from their point of view, found the highest and most valuable expression of Greek religious thought in the works of the great writers and philosophers. I may recall the names of such men as Lewis Campbell, James Adam, and Wilamowitz-Moellendorff. The philologists neglect or impatiently brush aside the popular aspects of Greek religion as less valuable and less well known. It is true that the religion of the masses was on a lower level than the religious ideas of eminent literary men, but it is also true that those ideas made hardly any impression on the development of Greek religion. The writers were not prophets, and the philosophers were seekers of wisdom, not of religious truth. The fate of religion is determined by the masses. The masses are, indeed, susceptible to high religious ideas if they are carried away by a religious genius, but only one such genius arose in Greece, Plato. Even he wished to be regarded as a philosopher rather than as a prophet, and he was accepted as such by his contemporaries. The religious importance of his thought did not come to the fore until half a millennium after his death, although since that time all religions have been subject to his influence.

I should perhaps mention a third kind of inquiry which has been taken up by scholars in recent years, especially in Germany. Their endeavors cannot properly be called research, however, for they have been directed to the systematizing of the religious ideas of the Greeks and the creation of a kind of theology, or, as the authors themselves express it, to revealing the intrinsic and lasting values of Greek religion. To this class belong, among others, W. F. Otto and E. Peterich. The great risk they run is that of imputing to the Greeks a systematization such as is found in religions which have laid down their creeds in books. The Greeks had religious ideas, of course, but they never made them into a system. What the Greeks called theology was either metaphysics, or the doctrine of the persons and works of the various gods.[1]

It is of the greatest importance to attain a well-founded knowledge of Greek popular religion, for the fate of Greek religion as a whole depended on it. It is incorrect to say that we have not the means to acquire such knowledge, for the means are at hand: first, in our information about the cults in which the piety of believers expressed itself; second, in hints by the writers of the classical period; and third, in archaeological discoveries. As I have stated, we ought not to mistake the popular religion for the primitive elements, which persisted in great measure but were subject to and influenced by the development of Greek civilization and political life.

In beginning my exposition of Greek popular religion I want to draw attention to a point of primary importance. In the latter part of the archaic age and in the classical age the leading cities of Greece were more and more industrialized and commercialized. Greek civilization was urban. Many parts of Greece, however, remained in a backward state, and while they are of no importance in the history of civilization and political life, they are important in the history of religion. For they still preserved the mode of life which had been common in earlier times, when the inhabitants of Greece were peasants, compelled to subsist on the products of their own country--the crops, the fruits, the flocks, and the herds.

In trying to understand Greek popular religion we must start from the agricultural and pastoral life of the countryside, which was neither very advanced nor very primitive culturally. The Greek peasant usually lived in a large village. Many ancient cities with names familiar in history were but villages similar to those found in Greece today. Let us imagine a Greek peasant. He rose early, as simple people always do, before dawn. In the dusk of the morning he looked for the stars which were beginning to wane above the eastern horizon, where the growing light announced the rising of the sun. The stars were for him only indications of the time of the year, not objects of worship. He greeted the rising sun with a kiss of the hand, as he greeted the first swallow or the first kite, but he did not pay it any reverence. He needed rain, and sometimes cool weather, more than he needed the sun. He looked at the highest mountaintop in the neighborhood. Maybe it wore a cloudcap. This was promising, for up there on the top of the mountain sat Zeus, the cloud-gatherer, the thrower of the thunderbolt, the rain-giver. He was a great god. He had other aspects of which we shall hear later. The roar of the thunder was the sign of his power and presence--sometimes of his anger. He smote the high mountains, the tall oaks, and occasionally man with his thunderbolt. But the flash of the lightning and the roar of the thunder were followed by the rain, which moistened the soil and benefited the crops, the grass, and the fruits.

It was seldom necessary to pray for rain in Greece, for the course of the seasons is much more regular there than in northern Europe. Late autumn and winter bring rain; summer brings drought and heat. On the other hand, the weather is not so regular that certain days of the year could be fixed upon for weather magic. This is the reason why as weather god Zeus had few festivals. Sometimes heat and drought were excessive. Myths have much to tell about these disasters, and it is related that they were sometimes so great that the most extreme of all sacrifices, a human sacrifice, was offered. Two such sacrifices are recorded from historical times, one to Zeus Lykaios and one to Zeus Laphystios.[2] Zeus Lykaios received his name from the high mountain in southwestern Arcadia, Lykaion, on the top of which he had a famous sanctuary. Zeus Laphystios was named after the mountain Laphystion in Boeotia, although his cult belonged to Halos in Thessaly. On Mount Lykaion there was a well called Hagno. When there was need of rain the priest of Zeus went to this well, performed ceremonies and prayers, and dipped an oak twig into the water. Thereupon a haze arose from the well and condensed into clouds, and soon there was rain all over Arcadia.

Zeus Laphystios is well known from the myth of the Golden Fleece, according to which Phrixos and Helle, who were to be sacrificed because of a drought, saved themselves by riding away on a ram with a golden fleece. Their mother was called Nephele (cloud). At the bottom of this myth is weather magic such as is known to have been practiced at several places in Greece, including Mount Pelion, not far from Halos. At the time of the greatest heat young men girt with fresh ram fleeces went up to the top of this mountain in order to pray to Zeus Akraios for cool weather.[3] From this fleece, Zeus was called Melosios on Naxos,[4] and the fleece, which was used in several rites, for example, in the initiation into the Eleusinian Mysteries, was called Zeus’ fleece (Dios kodion). It is generally said to have been a means of purification and propitiation, and so it was. But its origin is to be found in the weather magic by which the weather god was propitiated. It had a place at Athens in the cult of Zeus Maimaktes, the stormy Zeus, who gave his name to the stormy winter month of Maimakterion.

We are told that in other places, also, people went to the mountain of Zeus to pray for rain. Ombrios and Hyetios are common epithets of Zeus, and we hear of sanctuaries of Zeus on Olympus and on various other mountaintops, such as the highest mountain of the island of Aegina, where he was called Zeus Panhellenios. In this sanctuary a building was erected to accommodate his visitors. Probably the weather god Zeus ruled from the highest peak in every neighborhood. It is supposed that Hagios Elias, who nowadays has a chapel everywhere on the mountaintops, is his successor.

We follow our peasant on his way. We pass the gardens and cornfields where most of his work was done. We shall return to them later. We follow him to those parts of the countryside which were not subject to the labor of men--the meadows and the pasture grounds, the mountains and the forests. Even in modern Greece there are vast tracts of land which cannot be cultivated, and the extent of such land was greater in antiquity. If our peasant passed a heap of stones, as he was likely to do, he might lay another stone upon it. If a tall stone was erected on top of the heap, he might place before it a bit of his provision as an offering (Fig. 3). He performed this act as a result of custom, without knowing the real reason for it, but he knew that a god was embodied in the stone heap and in the tall stone standing on top of it. He named the god Hermes after the stone heap (herma) in which he dwelt, and he called the tall stone a herm. Such heaps were welcome landmarks to the wanderer who sought his way from one place to another through desert tracts, and their god became the protector of wayfarers. And if, by chance, the wayfarer found on the stone heap something, probably an offering, which would be welcome to the poor and hungry, he ascribed this lucky find to the grace of the god and called it a hermaion.

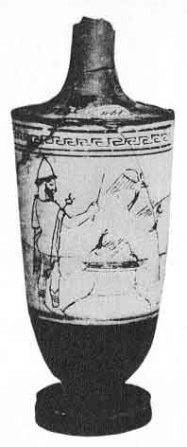

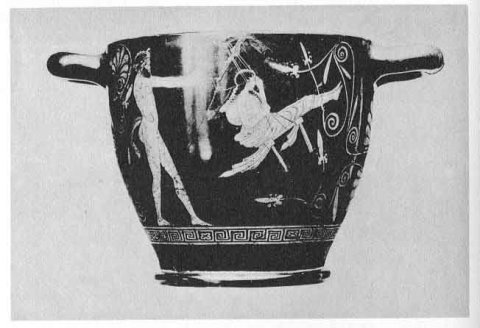

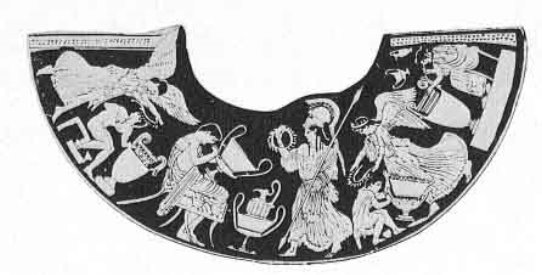

Our peasant or his forefathers knew that the stone heaps sometimes covered a dead man and that the stone erected on top was a tombstone. Accordingly, the god who dwelt in the stone heap had relations with the dead. Although the people brought libations and food offerings to the dead in their tombs, they also believed in a common dwelling place of the dead. Such contradictions are hardly noticed by simple people. This abode of the dead, the dark and gloomy Hades, was some-where far away beneath the earth. On leaving their earthly home, the souls needed someone to show them the way, and nobody was more appropriate for this function than the protector of wayfarers, who dwelt in the stone heaps. Hermes, the guide of souls, is known not only from literature but also from pictures, in which he is represented with a magic rod in his hand, permitting the souls, small winged human figures, to ascend and sending them down again through the mouth of a large jar (Fig. 2) . Such jars were often used for burial purposes.

Perhaps our peasant wanted to look after his stock, which grazed on the meadows and mountain slopes. The god of the stone heaps was concerned with them, too. The story, told in the Homeric Hymn, how, when a babe, he stole the oxen of Apollo, is a humorous folk tale invented by herdsmen who did not hesitate to augment their herds by fraud and rejoiced in such profitable tricks. One may think of the Biblical story of Jacob and Laban. To Hermes such stories were no boon, for he became the god of thieves.

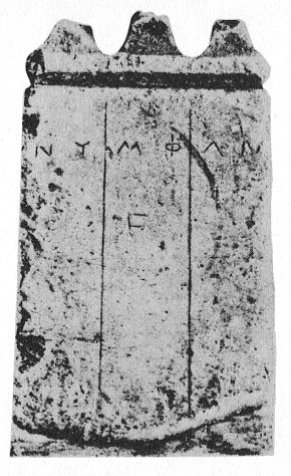

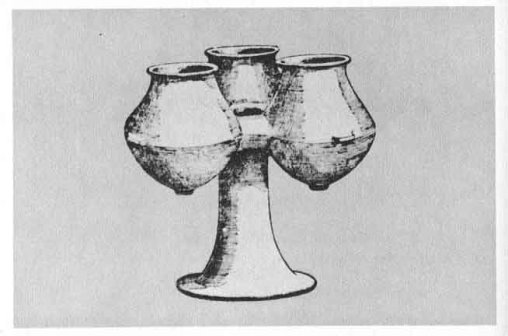

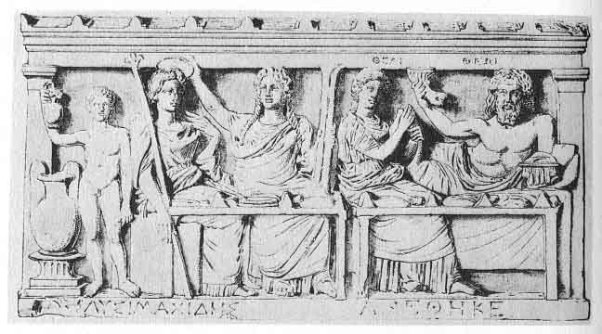

On Olympus Hermes was a subordinate god, the messenger of the gods, and we know him chiefly as such. I take no ac-count of later additions to his functions, which made him a god of commerce, of gymnastics, and of rhetoric. He was especially popular in one of the backward provinces of Greece, Arcadia, the land of shepherds. Here, too, the herms were especially popular in cult. Attention has recently been drawn to a series of Arcadian herms, some of which are double or triple and inscribed with the names of various gods in the genitive[5] (Fig. 1). Other gods than Hermes were also embodied in these stone pillars, a relic of the old stone cult, which has left many traces.

According to Hesiod and the Homeric Hymn, Hermes cared for and protected the livestock, but we do not find many evidences of this function in his cult. It fell to other gods. Apollo is called Lykeios, an epithet which surely describes him not as the light god but as the wolf god. And why should not the shepherds have appealed to the great averter of evil for protection against the most dangerous foe of their flocks, the wolf? Pastoral life found expression in another god who was always especially Arcadian, Pan. He came to Athens late--not until the time of the Persian wars. He is represented with the legs and face of a goat; he is as ruttish as the he-goat; he plays the syrinx, as the shepherds do in the lazy hours when the flocks graze peacefully; but he may also cause a sudden panic, when the animals, seized for some unknown reason by fright, rush away headlong.

There are many rivers in Greece, but few of them are large. Most of them are small and precipitous, and many are dry in summer. Water is scarce in Greece, and so the benefits received from the rivers are especially appreciated. In ancient times the rivers were holy. An army did not cross a river without making a sacrifice to it, and Hesiod prescribes that one should not cross a river without saying a prayer and washing one’s hands in its water. The aid of the rivers was sought for the fertility not only of the land but also of mankind. After the sixth century B.C., names taken from certain rivers were common, for instance, Kephisodotos, the gift of Kephisos. When the young man cut his long hair, he dedicated the locks to the neighboring river.

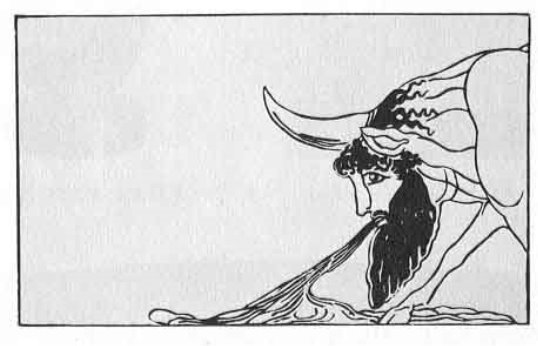

The rivers each had their god. These gods are represented in the shape of a bull or a bull with a human head (Fig. 6). Such a figure is sometimes called by the name of the great river in northwestern Greece, Acheloos, and Acheloos was venerated in several places in Greece. It is not clear whether the god of the river Acheloos was on his way to becoming a common river god or whether Acheloos is an old word for water. At all events, as the rivers were individualized, so too were their gods.

River spirits in the shape of a bull are well known from European folklore of the present day, and they are certainly an ancient heritage. The river spirit appears just as often, however, in the shape of a horse. This is true, for example, in Sweden and in Scotland. One of the great gods, Poseidon, is closely connected with the horse as well as with water. It is related in some myths that he appeared in the shape of a horse and that he created the horse. He brought forth a spring on the Acropolis of Athens with a stroke of his trident, and Pegasus brought forth the spring of Hippocrene on Mount Helicon with a stroke of his hoof. Other springs, such as Aganippe, also have names referring to the horse. No doubt the water spirit appeared in the shape of a horse also, but the springs had other deities who carried the day, the nymphs, to whom we shall come presently.

To the seafaring Ionians, Poseidon was the god of the sea. On the mainland of Greece, and especially in the Peloponnesus, he was the god of horses and of earthquakes. Earthquakes occur in Greece not infrequently, and when the earth began to tremble, the Spartans used to sing a paean to Poseidon. There is a certain connection between the rivers and the earthquakes, for many rivers in Greece sink down into the ground, eroding the limestone, and flow in subterranean channels for long distances until they break forth again in a mighty stream. The nature philosophers took over from the people the opinion that the earthquakes were caused by this eroding of the ground by the rivers. It is understandable, therefore, that the god of water was also the god of earthquakes. One of the epithets by which he was designated in Laconia, Gaiaochos, has been interpreted as “he who drives beneath the earth.”

The Greeks also knew other horse-shaped daemons, the centaurs and the seilenoi. The centaurs have in part the body of a horse and in part that of a man. Homer calls them beasts. They appear only in the myths of art and literature, and they seem to have been localized in two districts, Mount Pelion and northwestern Arcadia. There is no doubt that they were de-rived from popular belief. If the proposed etymology, according to which the word means “water whipper,”[6] is correct, they were water spirits. In that case, one might believe that they were originally spirits of the precipitous mountain torrents. At all events, their character is rough and violent. They resemble the spirits of wood and wilderness which appear in the folklore of northern Europe. They represent the fierce and rough aspects of nature. They are depicted as using uprooted fir trees for weapons and as carrying the victims of the chase on a pole.

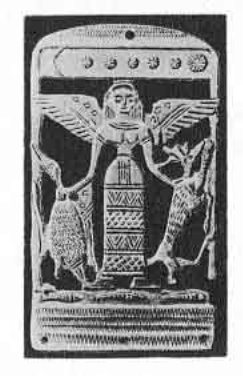

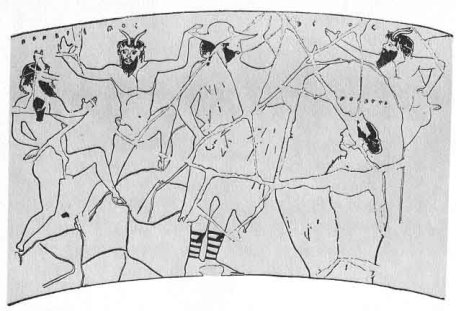

There is another kind of horse daemon, which is often represented in works of art of Ionian origin. These daemons are distinguished from the centaurs by having the body of a man with the legs and tail of a horse and by being ithyphallic. There has been a lengthy discussion concerning their name. It was proposed to assign to these daemons, which were confined to the Ionian area, the name of seilenoi--we know from inscriptions that they were so called--in distinction from the goatlike satyrs, which were supposed to be Dorian.[7] The attempt to make such a distinction has failed. Proper names prove that seilenoi were well known in the Peloponnesus also,[8] and their value as testimony is the greater because they prove that the seilenoi belong not only to mythology but also to popular belief. Moreover, there are archaic statuettes from Arcadia showing daemons with a human body and features of goats and other animals (Fig. 4). These goatlike daemons are sometimes called panes, and they are certainly akin to Pan. The seilenoi and the satyrs have intercourse with the nymphs, and very often they appear dancing and frolicking with the maenads, for they were made companions of Dionysus. We do not know the exact reason why this came about. It is supposed that they were fertility daemons, just as Dionysus was a vegetation god. As a consequence, they appear only in mythology, not in cult. But it is evident that the Greeks peopled untamed nature, the mountains and the forests, with various daemons which were thought of as having half-animal, half-human shape. This is one of the many similarities between Greek mythology and the popular beliefs of northern Europe, in which similar daemons and spirits are numerous. There can be no doubt that centaurs, seilenoi, and satyrs were created by popular belief, although art and literature appropriated them and they had no cult.

Like the peoples of northern Europe, the Greeks knew not only male but also female spirits of nature, the nymphs. The word signifies simply young women, and, unlike the male daemons, the nymphs are always thought of in purely human shape. They are beautiful and fond of dancing. They are benevolent. But they may also be angry and threatening. If a man goes mad it is said that he has been caught by the nymphs. In ancient Greek mythology, as elsewhere, we find the folktale motif of a man compelling a nymph to become his wife. She bears him children but soon returns to her native element. Thetis was originally a sea nymph whom Peleus won by wrestling with her. She soon abandoned his house and only returned from time to time to look after her son, Achilles. Nymphs are often mothers of mythical heroes.

The nymphs are almost omnipresent. They dwell on the mountains, in the cool caves, in the groves, in the meadows, and by the springs. There are also sea nymphs--the Nereids--and tree nymphs. The nymphs had cults at many places, especially at springs and in caves (Fig. 8). Caves with remains of such cults have been discovered. Most interesting is the cave at Vari on Mount Hymettus.[9] In the fifth century B.C., a poor man of Theraean origin, Archedemos, who styles himself “caught by the nymphs,” planted a garden, decorated the cave, and engraved inscriptions on its walls. Still more interesting is a cave which was recently discovered at Pitza in the neighborhood of Corinth.[10] The discovery is famous especially for its well-preserved paintings on wood in Corinthian style. One of these tablets represents a sacrifice to the nymphs, and the other represents women. There are a lot of terracottas representing women--some of whom are pregnant--Pan, satyrs, and various animals. The character of the cult and its connection with the nature daemons and with animals is evident, but, on the other hand, it appears that it was preeminently a cult of women and that the women applied to the nymphs for help in childbirth. Such cults are also found in other places. In the so-called prison of Socrates at Athens, where a century ago women brought offerings to the Moirai for success in marriage and childbirth,[11] the Moirai may have succeeded the nymphs. The nymphs were very popular in cult. They were beautiful and kind and represented the gentle and benevolent aspects of nature and of almost all its parts. It is quite understandable that they were venerated by women especially. Although the cults of women were not absolutely separated from those of men, men and women went different ways and had different occupations in daily life, as they still do in the Greek countryside. The women had their special concerns centering around marriage and childbirth, and it was only natural that they should apply to divinities of their own sex. The nymphs were to be found everywhere and were supposed to be especially benevolent to those of their own sex.

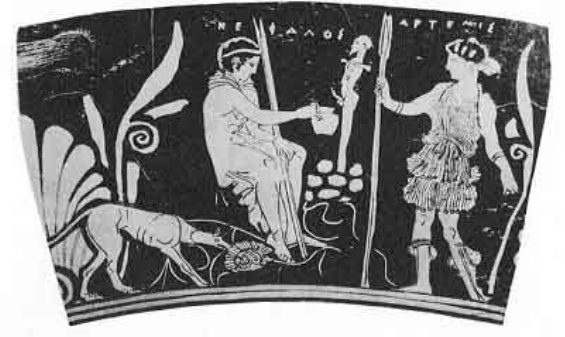

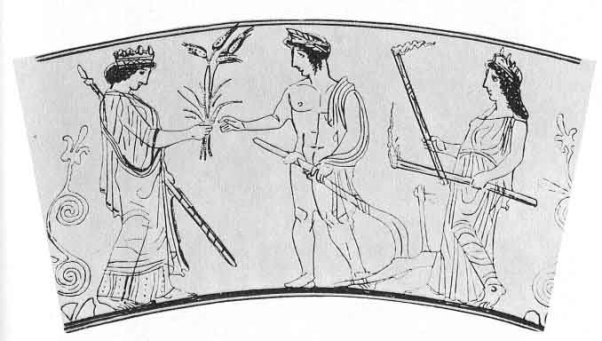

There is a great goddess who is very similar to the nymphs and who is accompanied by nymphs, namely Artemis, “Lady of the Wild Things” (Fig. 5). She haunts the mountains and the meadows; she is connected with the tree cult and with springs and rivers; she protects women in childbirth; and she watches over little children. Girls brought offerings to her before their marriage. Her aspect is different in different parts of Greece, but it always goes back to the general characteristics just mentioned, except that one or another of them comes more into the foreground. Her habitual appearance is determined by Homer and the great art and literature of Attica. She is the virgin twin sister of Apollo and by preference the goddess of hunting. How her relation to Apollo came about is not clear. We may only remark here that both carry the bow as their weapon. Of course, the goddess who haunts the mountains and the forests with a bow in her hand is a hunting goddess. Artemis was much more than that, but the Homeric knights, as well as the inhabitants of the great Ionian cities, had no relation to the free life of nature except in the sport of hunting, which they loved. Hence, this side of Artemis’ nature was especially emphasized.

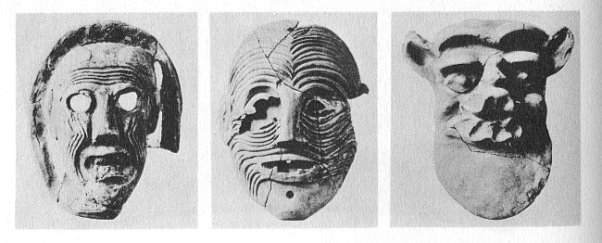

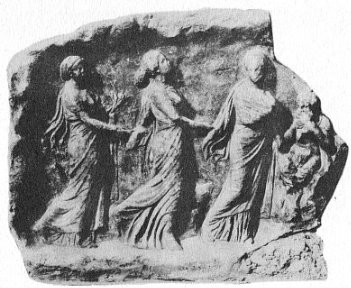

Other very interesting and very popular aspects of Artemis’ nature were prominent, especially in the Peloponnesus. She was closely connected with the tree cult. She is sometimes called Lygodesma, because her image was wound round with willow; Caryatis, after the chestnut; and Cedreatis, after the cedar. Dances and masquerades of a very free and even lascivious character assumed a prominent place in many of her cults, in which men as well as women took part. Cymbals have been found in the temple of Artemis Limnatis in the borderland between Laconia and Messenia.[12] During the excavations of the British School in the famous sanctuary of Artemis Orthia at Sparta, a number of terracotta masks, representing grotesque faces of both men and women, were found (Fig. 7) . It is very probable that similar masks were worn by the dancers who performed in this cult. In these customs we find the popular background for the mythological Artemis who dances with her nymphs.

Artemis was the most popular goddess of Greece. She was the leader of the nymphs, and, in fact, she herself was but the foremost of the nymphs. Archedemos, who decorated the cave of Vari, dedicated his inscriptions to the nymphs, but one of them is addressed to the Nymph, in the singular. One of the crowd of nymphs was singled out as a representative of them all, and she became the great goddess Artemis.

Christianity easily swept away the great gods, but the minor daemons of popular belief offered a stubborn resistance. They were nearer the living rock. The Greek peasant of today still believes in the nymphs, though he gives them all the old name of the sea nymphs, Neraids. They haunt the same places, they have the same appearance and the same occupations, and the same tales are told of them. It is remarkable that they have a queen, called “the Great Lady,” “the Fair Lady,” or even “the Queen of the Mountains.” Perhaps she is a last remembrance of the great goddess Artemis, or perhaps there has been a recurrence of the process by which Artemis, the foremost of the nymphs, became a great goddess. Nobody knows, but the fact that the nymphs alone survive in modern popular belief is a telling argument for their popularity among the Greek people in ancient times.

What interests primitive man is not nature in itself but nature so far as it intervenes in human life and forms a necessary and obvious basis for it. In the foreground are the needs of man together with nature as a means of satisfying those needs, for upon the generosity of nature depends whether men shall starve or live in abundance. Therefore, in a scantily watered land such as Greece, the groves and meadows where the water produces a rich vegetation are the dwelling places of the nature spirits, and so are the forests and mountains where the wild beasts live. In the forests the nymphs dance; centaurs, satyrs, and seilenoi roam about; and Pan protects the herds, though he may also drive them away in a panic. The life of nature becomes centered in Artemis, who loves hills and groves and well-watered places and promotes that natural fertility which does not depend upon the efforts of man.

Anyone who wishes to understand the religion of antiquity should have before him a living picture of the ancient landscape as it is represented in certain Pompeian frescoes[13] (Fig. 9) and in Strabo’s description of the lowland at the mouth of the river Alpheus.[14] ”The whole tract,” Strabo says, “is full of shrines of Artemis, Aphrodite, and the nymphs, in flowery groves, due mainly to the abundance of water; there are numerous hermae on the roads and shrines of Poseidon on the headlands by the sea.” One could hardly have taken a step out of doors without meeting a little shrine, a sacred enclosure, an image, a sacred stone, or a sacred tree. Nymphs lived in every cave and fountain. This was the most persistent, though not the highest, form of Greek religion. It outlived the fall of the great gods.

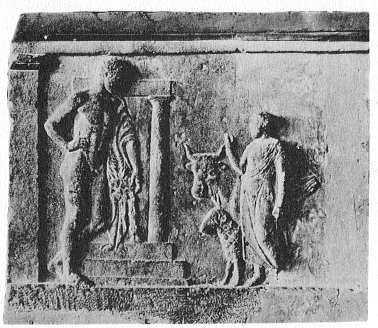

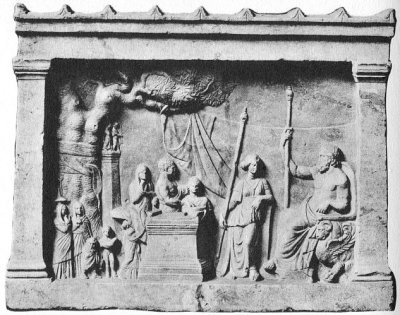

This is not the end of the story. Our peasant certainly passed on his way other small sanctuaries or groves where he paid his respects. Not gods or nature daemons but heroes dwelt in them[15] (Fig. 10). Although modern scholars have proffered other opinions, the Greeks were persuaded that a hero was a man who had once lived, who died and was buried, and who lay in his grave at the place where he was venerated. I should think it likely that our peasant had heard weird stories about heroes, such as those about the hero of Temesa, to whom the most beautiful virgin of the town had to be sacrificed until the famous boxer Euthymus drove him out in a regular fight, or about the hero Orestes, whom the Athenians did not like to meet at night because he was apt to give them a beating and to tear off their clothes. If our peasant became sick he believed, perhaps, that some hero had attacked him. In other words, ghost stories such as are not yet forgotten were told of the heroes. The hero was a dead man who walked about corporeally, a revenant such as popular belief tells of everywhere. But this aspect of the heroes lingered only in the background, for in Greece the heroes had cults and were generally helpful. Their cult was bound to their tomb, and their power was bound to their relics, which were buried in the tomb. This is the reason why their bones were sometimes dug up and transferred to another place. Cimon, for example, fetched the bones of Theseus from the island of Scyros to Athens, and the Lacedaemonians with some difficulty found the bones of Orestes beneath a smithy at Tegea and transferred them to Sparta when they wanted his help in the war against the Arcadians. The heroes were especially helpful in war. The sense which the word “hero” had in Homer, namely “warrior,” was not forgotten either, and the heroes were particularly well suited to defend the land in which they were buried. In the battle of Marathon, Theseus rose from the ground to fight with his people against the Persians. The Locrians in Italy left a place open in the file for Aias, and in the battle of Sagra he was said to have wounded the commander of their foes, the Crotoniates. It sometimes occurred that a people sent its heroes to help another people.

There were an exceedingly large number of hero tombs and sanctuaries all over the countryside. The names of only the best known of these heroes, and especially those with mythological names, are recorded. Very many were anonymous or called only by some such epithet as “the leader.” Others were designated simply by the place where their cult was located. This fact emerges, for example, from the sacrificial calendar of the Marathonian tetrapolis,[16] in which we find four couples, each consisting of a hero and a heroine, and in addition to these some other heroes. In the inscription of the Salaminioi,[17] which was discovered recently during the American excavations at Athens, we also find a series of heroes designated by the localities of their cults in the neighborhood of Sunium.

The heroes were exceedingly numerous; they were found everywhere; and they were close to the people. They were thought to appear in very concrete form. It is not to be wondered at that the people applied to them for help in all their needs. They were often healers of diseases, like the Mohammedan saints, whose tombs are often hung with patches torn from the clothes of the sick. Asclepius himself was a hero. He ousted many other heroes who were locally venerated as healers of sickness. Thus the heroes were good for almost everything, and this fact explains why minor local gods who were too insignificant to be reckoned as true gods were received among the number of the heroes. This is the reason why some scholars were prone to consider the heroes as debased gods or “special gods.” I cannot enter into this complicated problem, which Farnell has treated fully in his book on the hero cults. I have only wished to give a concrete idea of the importance of the cult of the heroes for the Greek people.

The similarity of the heroes to the saints of the Catholic Church is striking and has often been pointed out. The power of the saints, like that of the heroes, is bound to their relics, and just as the relics of the saints are transferred from one place to another, so were those of the heroes. Moreover, the oracle of Delphi prescribed that a hero cult should be devoted to a dead man if it appeared that a supernatural power was attached to his relics, and the pope canonizes a saint for similar reasons. The cult of the heroes corresponded to a popular need which was so strong that it continued to exist in Christian garb.

I have tried to give as well as possible in a limited space a concrete idea of Greek rustic religion as far as it was concerned with the free life of nature and with the heroes. Nature was peopled with spirits, daemons, and gods. They haunted the mountains and the forests. They dwelt in trees and stones, in rivers and wells. Some of them were rough and dreadful, as the wilderness is, while others were gentle and benevolent. Some of them promoted the life of nature and also protected mankind. The great gods are less prominent in this sphere. Zeus holds his place as the god of the weather, the hurler of the thunderbolt, and the sender of rain. Poseidon appears as the god of water and earthquakes. Hermes is really a minor god, the spirit embodied in the stone heaps, who has been introduced into Olympus by Homeric poetry. Artemis is the foremost of the nymphs who has grown into a great goddess. The innumerable heroes are protectors of the soil in which their bones are laid, ready to help their fellow countrymen in all their needs, linked with both the past and the present.

This aspect of Greek religion was certainly not the highest, but it was the most enduring. It was close to the earth, which is the source of all religion and from which even the great gods sprang. The great gods were overthrown and soon forgotten by the people. The nature daemons and the heroes were not so easily dealt with. The nature spirits have lived on in the mind of the people to this day, as they have in other parts of Europe, although they were not acknowledged by the Church, which called them evil daemons, nor by educated people, who regarded them as products of superstition. The cult of the heroes took on a Christian guise and survived in much the same forms, except that the martyrs and the saints succeeded the heroes.

These facts prove that we have here encountered a religion which corresponds to deep-lying ideas and needs of humanity. They also prove the importance of this kind of religion in antiquity. It was a religion of simple and unlettered peasants, but it was the most persistent form of Greek religion.

Rural Customs And Festivals

I have emphasized strongly the fact that except for a few industrial and commercial centers ancient Greece was a country of peasants and herdsmen and that according to modern notions many of its so-called cities were but large villages. Certain provinces such as Boeotia, Phocis, and Thessaly, not to speak of Messenia, were always agricultural. In other ways also some of them were still very simple and backward in the classical age. Examples are Arcadia, Aetolia, and Acarnania. Except for those cities to which the leading role in Greek history fell, Greece depended on agriculture and on cattle and sheep raising. In early times, before the industrial and commercial development began, this was true of the whole of Greece, and it was then that the foundations of the Greek cults were laid.

I want to stress this fact and certain of its implications once more. Corn, wheat, or barley was always the staple food of the Greeks. The daily portion of food of soldiers, laborers, and slaves was always reckoned as a certain number of pecks of corn. With the bread, some olives, some figs, or a little goat-milk cheese was eaten and a little wine was drunk. The diet of the Greek peasant is the same even today. Meat was not daily or common food. One might slaughter an animal in order to entertain a guest, as Eumaeus did when Odysseus came to his hut, but this was considered as a sacrifice also. Generally speaking, the common people ate meat only at the sacrifices which accompanied the great festivals. One is re-minded of the great feasting on mutton at Easter in modern Greece, where the peasants seldom eat meat. It will be well to keep this background of Greek life in mind when we try to expound the rural customs of ancient Greece.

The significance of agriculture in the popular festivals occurred even to the ancients. Aristotle says that in early times sacrifices and assemblies took place especially after the harvest had been gathered because people had most leisure at this time.[18] A late author, Maximus of Tyre, writes on this topic at greater length.[19] Only the peasants seem, he says, to have instituted festivals and initiations; they are the first who instituted dancing choruses for Dionysus at the wine press and initiations for Demeter on the threshing floor. A survey of the Greek festivals with rites which are really important from a religious point of view shows that an astonishing number of them are agricultural. The importance of agriculture in the life of the people in ancient times is reflected even in the religious rites.

The significance of agriculture in the festivals founded on religious rites goes still further. The Greek calendar is a calendar of festivals promulgated under the protection of Apollo at Delphi in order that the rites due to the gods might be celebrated at the right times. But long before Apollo had appropriated the Delphic oracle for himself, agriculture had created a natural calendar. Agricultural tasks succeed each other in due order because they are bound up with the seasons, and so also do the rites and ceremonies which are connected with these tasks of sowing, reaping, threshing, gardening, and fruit gathering. For all of them divine protection is required and is afforded by certain rites which belong, generally speaking, to an old religious stratum and which have a magical character. Such customs, very similar to those of the Greeks, have been preserved by the European peasantry down to our own day.

The Greek goddess of agriculture was Demeter, together with her daughter Kore, the Maiden. The meaning of -meter is “mother.” In regard to the first syllable, de-, philologists are at variance as to whether it means “earth” or “corn.” The cult proves that Demeter is the Corn Mother and her daughter the Corn Maiden. Demeter is not a goddess of vegetation in general but of the cultivation of cereals specifically. The Homeric knights did not care much for this goddess of the peasants. The references to her in Homer are few, but they are sufficient to show that she was the corn goddess who presided at the winnowing of the corn. Hesiod, who was himself a peasant and composed a poem for peasants, mentions her often. For instance, he prescribes a prayer to Demeter and Zeus in the earth that the fruit of Demeter may be full and heavy when the handle of the plow is grasped in order to begin the sowing, and he calls sowing, plowing, harvesting, and the other agricultural labors the works of Demeter.

Agricultural labors were accompanied by rites and festivals, most of which were devoted to Demeter. At the autumn sowing the Thesmophoria was celebrated; in the winter, during which the crops grow and thrive in Greece, sacrifices were brought to Demeter Chloe (the verdure); and when the corn was threshed the Thalysia was celebrated. Best known is the festival of the autumn sowing, the Thesmophoria. There is no other festival for which we have so many testimonies from various places. Demeter herself was called thesmophoros, and she and her daughter were the two thesmophoroi. The epithet has been translated legifera. In this interpretation thesmos is taken in the sense of “law” or “ordinance” and reference is made to the conception of agriculture as the foundation of a civilized life and of obedience to the laws. This idea comes to the fore in the Eleusinian Mysteries, which were originally a festival of the autumn sowing like the Thesmophoria to which they were closely akin.[20] It is said that the gift of Demeter is the reason why men do not live like wild beasts, and Athens is praised as the cradle of agriculture and of civilization.

But this interpretation of the word is late and erroneous. It arose only after men had begun to reflect and had recognized that agriculture is the foundation of a civilized life. Thesmos signifies simply “something that has been laid down,” and in compound names of festivals ending in -phoria the first part of the compound refers to something carried in the festival. Oschophoria, for example, means the carrying of branches. The thesmoi, consequently, were things carried in the rites of the Thesmophoria, and we know what these things were. At a certain time of the year, perhaps at another festival of Demeter and Kore, the Skirophoria, which was celebrated at the time of threshing, pigs were thrown into subterranean caves together with other fertility charms. At the Thesmophoria the putrefied remains were brought, mixed with the seed corn, and laid on the altars. This is a very simple and old-fashioned fertility magic known from Athens as well as from other places in Greece. The swine was the holy animal of Demeter.

The Thesmophoria and some other festivals of Demeter were celebrated by women alone; men were excluded. Some scholars have thought that the reason for this was that the Thesmophoria had come down from very ancient times when the cultivation of plants was in the hands of the women. This can hardly be so, for the cultivation of cereals with the help of the plow drawn by oxen has always been the concern of men. The Thesmophoria was a fertility festival in which the women prayed for fertility not only for the fields but also for themselves. The parallelism of sowing and begetting is constant in the Greek language. The reason why this festival was celebrated by women alone may simply be that the women seemed especially fit for performing fertility magic.

While the festival of the autumn sowing is very often mentioned, references to the corresponding festival of the harvest, the Thalysia, are curiously few. It is, however, the only festival mentioned in Homer, who says that sacrifices were offered on the threshing floor. Theocritus describes it in his lovely seventh idyl, in the last lines of which he mentions the altar of Demeter of the threshing floor and prays that he may once again thrust his winnowing shovel into her corn heap and that she may stand there smiling with sheaves and poppies in both hands. In modern Europe the harvest home is a very popular rustic festival. The contrast between the popularity of the modern harvest home and the few references to the ancient harvest festival of the Thalysia is probably only seeming. The rites of the autumn sowing, having become a state festival, were celebrated on certain days of the calendar, while the harvest home was in Greece a private festival celebrated on every farm when the threshing was ended and its date was not fixed. It may be added that the harvest is conducted differently in Greece than in northern Europe. The sheaves are not stored in a barn but are brought immediately to the threshing floor and threshed. The harvest in the coast districts falls in May and the threshing at the beginning of June in the dry season when rain is not to be expected. Another harvest festival was probably the Kalamaia, which was not uncommon, though very little is known about it. Its name, derived from kalamos (stalk of wheat), its time--June--and its connection with Demeter seem to prove its harvest character.

As becomes a harvest festival, first fruits were offered at the Thalysia. A loaf baked of the new corn was called thalysion arton. These loaves are also mentioned in other connections, and Demeter herself received the name of the “goddess with the great loaves.” In Attica such a loaf was called thargelos, and it gave its name to another well-known festival, the Thargelia. This festival, however, belongs to Apollo, not to Demeter. Its characteristic rite is quite peculiar, and its meaning is much discussed. A man, generally a criminal, was led around through the streets, fed, flogged with green branches, and finally expelled or killed. He was called pharmakos, which is the masculine form of pharmakon (medicine). Some scholars regard the pharmakos as a scapegoat on whom the sins and the impurity of the people were loaded and who was then expelled or destroyed. They are certainly right. Others have thought that he was a vegetation spirit which was expelled in order to be replaced by a new one. This opinion, too, is not quite unfounded, for fertility magic is conspicuous in the rites. A crossing of various rites has taken place, as happens not infrequently.[21]

The purificatory character of the central rite of the Thargelia explains why the festival was dedicated to Apollo, who is the god of purifications. Purificatory rites are needed and often performed when the crops are ripening in order to protect them against evil influences, and this was probably the original purpose of leading around the pharmakos. References to similar magical rites abound in the writings about agriculture by later authors and are found elsewhere as well. Theoretically, two different kinds of rites can be distinguished, though they are often mixed up. One consists in walking about with some magical object in order that its influence may be spread over the area. The other is encirclement.[22] Conducting the pharmakos through the streets of the town belongs to the former class. So does a kind of magic prescribed for destroying vermin, which required that a nude virgin or a menstruating woman should walk about in the fields or gardens. In the other case, a magic circle is drawn which excludes the evil. It is related of Methana that when winds threatened to destroy the vines, two men cut a cock into two pieces and, each taking a bleeding piece, ran around the vineyard in opposite directions until they met. Thus the magic circle was closed. Magic of a corresponding kind is still practiced in modern times. The leading around of the pharmakos is probably an old agrarian rite which was introduced into the towns and extended to the expelling of all kinds of evil.

Thus, a connection can be established between the chief rite of the Thargelia and the agrarian character of the festival, which is proved by the derivation of its name from thargelos, the loaf offered as first fruit. This presents a certain difficulty, because the Thargelia was celebrated on the seventh day of the month Thargelion, a date which commonly falls a little before harvest time. But it is not without precedent to use unripe ears for the first fruits. The vestal virgins at Rome did so in preparing the mola salsa at the commencement of May.

First fruits are commonly considered as a thank offering to the gods, and many people may have brought them with this intention. But like most of the rites and customs discussed here, the offering of first fruits is pre-deistic and older than the cult of the gods. Its origin is to be found in magic. Among many primitive peoples certain plants and small animals are tabooed during a particular time, and the lifting of the taboo so that they can be used for food is effected by elaborate ceremonies, which are also intended to bring about an increase of these plants and animals. Some scholars are of the opinion that among the Greeks, too, the offering of first fruits and the ceremonial drinking of new wine, of which I shall speak later, represented the breaking of the taboo imposed upon the unripe cereals and wine.[23] Perhaps they are right in regard to the ancient times, about which we have no direct information. The information which has come down to us from the Greeks proves that they themselves thought that the aim of the offering of first fruits was the promotion of fertility. The loaf called thargelos was also called eueteria (a good year). It is said, furthermore, that thargela were fruits of all kinds which were cooked in a pot and carried around as offerings of first fruits to the gods. The loaf and the mixture of fruit cooked together belong to two different forms of the same custom, to which many parallels are found among modern European peoples, especially in the harvest customs of eating ceremonially some part of the harvest. We have found this custom in the harvest festival of the Thalysia and in the Thargelia, which was celebrated a little before the harvest. It also occurs in the Pyanopsia, which received its name from the cooking of beans in a pot. The Pyanopsia was celebrated in the month of Pyanopsion in late autumn and was a festival of fruit gathering. The eiresione (the May bough), about which we shall have something to say later, was also carried around at this festival. The Pyanopsia, as the festival of the fruit harvest, corresponds to the Thalysia, the festival of the cereal harvest.

The meaning of such offerings appears very clearly in an ancient Sicilian custom, which was recorded by ancient students of literature because they believed that they had found in it the origin of bucolic poetry.[24] The so-called bucoliasts went around to people’s doors. The goddess with whom the custom came to be associated was Artemis, but the practices which characterize it prove that it belongs among those which we are describing. The bucoliasts wore hartshorns on their heads and carried loaves stamped with figures of animals (this was a concession to the goddess with whom the custom was associated), a sack of fruit of all kinds, and a skin of wine. They strewed the fruit on the thresholds of the houses, offered a drink of wine to the inhabitants, and sang a simple song: “Take the good luck, take the health-bread which we bring from the goddess.” What they carried may, in fact, be called a panspermia, and the partaking of it conferred luck on the inhabitants of the houses. Similar customs were fairly common. A newly acquired slave and the bridegroom at a wedding were strewn with fruit (katachysmata).[25] The custom of strewing the bridegroom with fruit still persists, but its original sense of conferring fertility is forgotten.

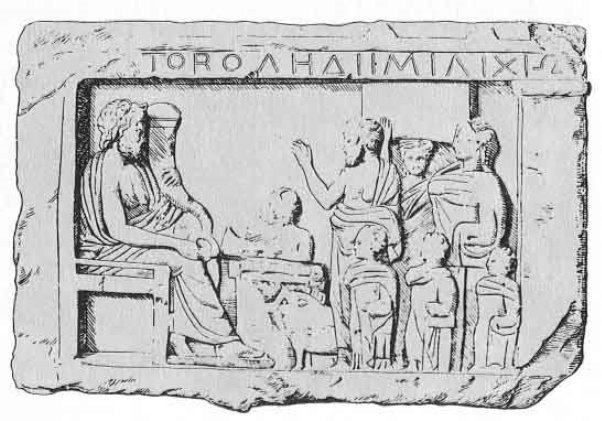

This kind of offering is commonly called panspermia, although the Greeks also called it pankarpia. Both words signify a mixture of all kinds of fruit. Such offerings were also brought to the dead at the ancient Greek equivalent of All Souls’ Day, the Chytroi, on the third day of the Anthesteria. It is very interesting that this usage seems to have persisted probably from prehistoric down to modern times. We are told of a vessel, called kernos, with many small cups which were filled with fruit of various kinds and with fluids such as wine and oil. In the middle was a lamp. The women carried the kernos on their heads in the Eleusinian Mysteries. Very similar is the liknon or winnowing basket filled with fruit, among which a phallus was fixed. It appears in the representations of the Dionysiac Mysteries and is only another way of presenting offerings of the same kind. Vessels of the same shape as the kernos have been found in Minoan Crete and elsewhere, and the conclusion seems to be justified that offerings of this kind were made in the prehistoric age (Fig. 11) . The custom has been taken over by the Greek Church. The panspermia is offered to the dead on the modern Greek All Souls’ Day, the Psychosabbaton, which is celebrated in the churchyards before Lent or before Whitsunday. It is offered as first fruits on various occasions, but especially at the harvest and at the gathering of the fruit. It is brought to the church, blessed by the priest, and eaten in part, at least, by the celebrants. This modern panspermia varies according to the seasons and consists of grapes, loaves, corn, wine, and oil. Candles are fixed in the loaves, and there are candlesticks with cups for corn, wine, and oil, which have been compared to the ancient kernos.[26] The usual modern name of these offerings is kollyba, which signified in late antiquity as well as in modern times an offering of cooked wheat and fruit. The word appears also in descriptions of ecclesiastical usages from the Middle Ages.[27] Very seldom can the continuity of a cult usage be followed through the ages as this one can. These popular customs, which belong to the oldest and, as some may say, the lowest stratum of religion, are the most long-lived of all.

Up to this point we have dealt chiefly with customs and usages connected with the cultivation of cereals, although in the later paragraphs we have mentioned also some customs pertaining to fruit gathering. As I have remarked, fruit was an important part of the daily food of the Greeks, although we must keep in mind that certain kinds familiar to us, such as oranges, were introduced in recent times. Of wine I need not speak. The cultivation of the olive was very important. Olives were not only eaten as a condiment with bread but also provided the fat which man needs. The oil served for illumination and as a cosmetic. But no special customs referring to the cultivation of the olive are recorded. We know only that at Athens it was protected by Zeus and Athena and that there were sacred olive trees from which came the oil distributed as prizes at the Panathenaean games.

Starting from the beginning of the year, we find a festival celebrated at Athens about the commencement of January. Our information about it and even its name seem to be contradictory. The name, Haloa,[28] is derived from halos, which means both threshing floor and garden. Since the first sense of the word would be inapplicable to a festival celebrated in January, it must have been a gardening festival. It is said to have comprised Mysteries of Demeter, Kore, and Dionysus and to have been celebrated by the women on the occasion of the pruning of the vines and the tasting of the wine. It bore a certain resemblance to the Thesmophoria, and sexual symbols were conspicuous in it. If we think of the labors in the vineyards of modern Greece, this account is intelligible though not quite correct. In December the soil is hoed around the vines, and their roots are cut. At the same time the first fermentation of the wine is ended, and the wine can be drunk, although it is not very good. Thus, the description of the Haloa fits in with what we know about the labors in the vine-yards. On the other hand, the Haloa is also said to have been a festival of Demeter, and this, too, is possible. The crops grow and thrive during the winter, and, as we have seen, sacrifices were brought to Demeter Chloe at this time.

In February the vines are pruned, and the second fermentation of the wine comes to an end. The wine is now ripe for drinking. One of the most popular and most complex of the festivals at Athens, the Anthesteria, fell in this season, when spring had come with plenty of flowers. The name means “festival of flowers.” We hear of festivals celebrated in other parts of Greece at the season when the vines were pruned. The Aiora, or swinging festival, of the Attic countryside seems to have been of this nature. It was connected with the myth of Icarius, who taught the culture of the vine, and with the Anthesteria. It was a rustic merrymaking. Youths leaped on skin sacks filled with wine, and the girls were swung in swings, a custom which is common in rustic festivals and may perhaps be interpreted as a fertility charm[29] (Fig. 12).

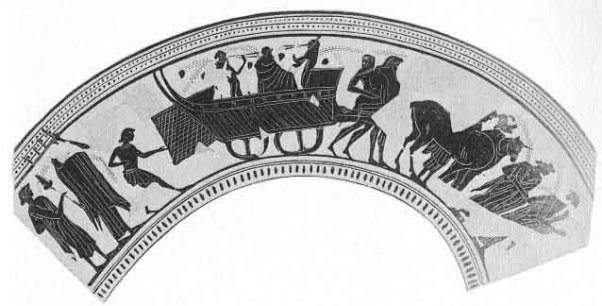

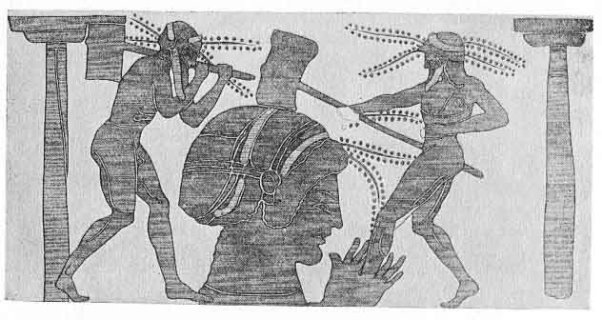

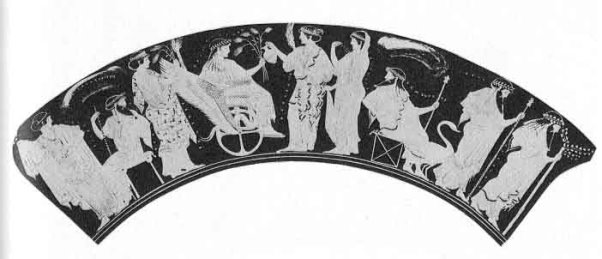

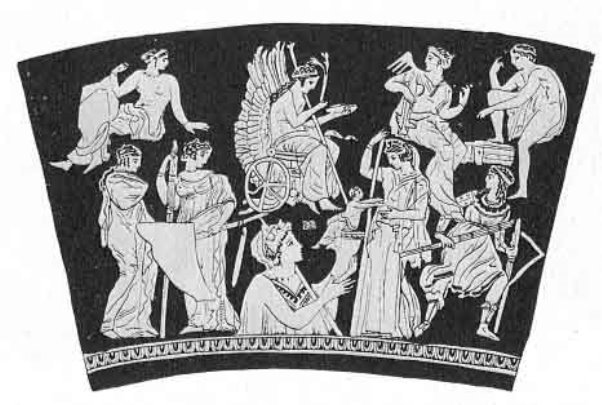

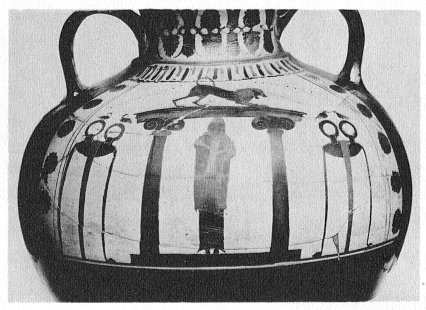

In the city of Athens the most prominent part of the Anthesteria was the blessing and ceremonial drinking of the new wine. The first day, called Pithoigia, had its name from the opening of the wine jars. In Boeotia a similar custom was observed at about the same time, but it was devoted to Agathos Daimon, the god to whom the libation after every meal was made. At Athens the wine was brought to the sanctuary of Dionysus in the Marshes, mixed by the priestesses, and blessed before the god. Everyone took his portion in a small jug, and hence this day is called “the Festival of the Jugs” (Choes). Even the small children got their share and received small gifts, particularly little painted jugs. The schools had a vacation, and the teachers received their meager fee. The admission to this festival at the age of about four years was a token that a child was no longer a mere baby. Another rite pertaining to the Anthesteria was the ceremonial wedding between Dionysus and the wife of the highest sacral official of Athens, the king archon. This is an instance of a widespread rite intended to promote fertility. Examples abound in the folklore of other countries. In Greece they are mostly mythical. At Athens the god was driven into the city in a ship set on wheels (Fig. 13). He was the god of spring coming from the sea.

It is impossible to enter here into a discussion of the very complex rites comprised in the Anthesteria.[30] It should be re-marked, however, that the third day, or, more correctly, the evening before it, was gloomy. It was the Athenian All Souls’ Day. Offerings of vegetables were brought to the dead, and libations of water were poured out to them. The Anthesteria has a curious resemblance to the popular celebration of Christmas in the Scandinavian countries. Many of the customs observed there at Christmas evidently refer to fertility. People eat and drink heartily and there is much merrymaking. But there is also a gloomy side to the celebration. The dead visit their old houses, where beds and food are prepared for them. There is of course no connection between this festival and the Anthesteria, but only a curious similarity. The popular customs of all countries and of all ages are related.

Vintage festivals are rare in classical Greece. There was one at Athens, the Oschophoria, which got its name from the vine branches laden with grapes which were carried by two youths from the sanctuary of Dionysus to the temple of Athena Skiras. A race followed, and the victor received for a prize a drink made up of five ingredients. At Sparta there was a race of youths, called staphylodromoi (grape-runners), at the great festival of the Carnea, which was celebrated about the beginning of September. The name proves that the custom had something to do with the vintage. One of the youths put fillets on his head and ran on before the others, pronouncing blessings upon the town. It was a good omen if he was overtaken by the others and a bad omen if he was not. Many speculations concerning this custom have been advanced, but we cannot with certainty say more than that it seems to have been an old vintage custom. The race reminds one of the race at the Oschophoria.

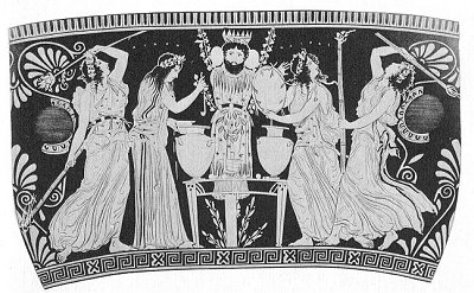

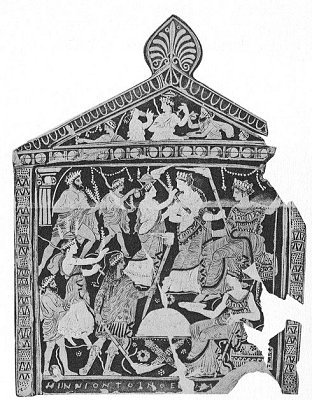

The association of Dionysus with festivals of viticulture is not nearly so constant as that of Demeter with the cultivation of cereals. The reason is not hard to find. Dionysus came to Greece at a fairly late date--a little before the beginning of the historical age. Viticulture is much older in Greece than he, and the rustic customs which have been described here are very ancient, pre-deistic, magical rites which were not associated with a god until a later time, when it seemed that every festival should be dedicated to a god. The connection was not indissoluble. The gods have vanished, but the customs still persist in part. It is the general belief that Dionysus was above all the god of wine (Fig. 14). Already in Hesiod and Homer wine was his gift. He was not the god of wine alone, however, but of vegetation and fertility in general, though not of cereals. The fig also was a gift from him.[31] In the festival of flowers, the Anthesteria, he appeared as the god of spring.

This explains why the phallus was his symbol. The phallus was used in other fertility cults, especially in the festivals of Demeter, but it was nowhere so conspicuous as in the cult of Dionysus. It was carried in all Dionysiac processions. The colonies of Athens were required to send phalli to the Great Dionysia. The procession at this festival, during which the great works of the tragic and comic poets were performed, would make a grotesque impression upon us if we were able to see it with its many indecent symbols. Another Dionysiac festival with a phallus procession was the Rustic Dionysia, which is described by Aristophanes. Rural customs of this sort are mentioned also by Plutarch, who complains that these simple and merry festivals have been ousted by the luxurious life of his times. Comedy had its origin in the jokes and funny songs of the carriers of the phalli. Tragedy also originated in the cult of Dionysus--the cult of Dionysus of Eleutherai, a village in the Boeotian borderland. This cult was brought to Athens by Pisistratus. We ought to keep in mind that in this cult Dionysus was called Melanaigis (he with the black goat-skin) and that there was a myth which proves that a combat between “the Light One” and “the Black One” was enacted. Whether this was the same combat between winter and summer which is found in later European folklore, as some scholars think, I dare not say.[32] But it may not be useless to observe that two of the highest achievements of the Greek spirit, the drama and bucolic poetry, had their origin in simple rural customs.

I have mentioned the eiresione, the May bough, which was carried in the festival of the fruit gathering, the Pyanopsia. It is described in a fragment of a popular song as a branch with leaves hung with figs, loaves, and cups of honey, wine, and oil.[33] So far it is reminiscent of the panspermia, and it is an appropriate symbol for a festival of fruit gathering. It was carried by a boy whose father and mother were both alive, and it was set up before the temple of Apollo or before the doors of private houses. There it remained until it was dry and likely to take fire. We may guess that it was perhaps exchanged for a new one the following year, just as the modern bouquet de moisson, a sheaf decorated with flowers and ribbons, is nailed above the door of the barn at harvest time and remains there until it is exchanged for a new one at the next harvest. The eiresione was also carried at the late spring festival of the Thargelia, mentioned above, and on the island of Samos boys went around carrying the eiresione and asking for alms. The biography of Homer falsely attributed to Herodotus has preserved many precious bits of popular poetry, and among them is the song which the boys sang when they carried the eiresione about. “We come,” they sang, “to the house of a rich man. Let the doors be opened, for Wealth enters, and with him Joy and Peace. Let the jars always be filled and let a high cap rise in the kneading trough. Let the son of the house marry and the daughter weave a precious web.” The procession and song strikingly resemble modern rural customs in which youths go around asking for alms. To adduce only one example out of many, in southern Sweden they carry green branches, which they fasten to the houses, and sing a song like the ancient Greek one containing wishes for good luck and fertility. This is done on the morning of the first of May. We have already met a similar procession, that of the bucoliasts in Sicily, who carried around and distributed a panspermia, wished good luck, and asked for alms. On the Cyclades the women went around singing a hymn to the Hyperborean virgins and collecting alms for them.[34] It may be supposed that this custom had something to do with the myth of these virgins and the sheaves which were brought from the Hyperboreans to Delos.

On the island of Rhodes the boys carried a swallow around at the commencement of spring. They began by singing: “The swallow has come bringing the good season and good years.” They then asked for loaves, wine, cheese, and wheat porridge. If they were not given anything, they ended with threats. Such threats are often a feature in modern customs also.[35] The poet Phoenix of Colophon, who lived in the third century B.C., composed a similar song for boys who carried a crow.[36] Not only has this custom many parallels in modern times, but it can be demonstrated that it has survived in Greece since antiquity. On the first of March the boys make a wooden image of a swallow, which revolves on a pivot and is adorned with flowers. The boys then go from house to house singing a song, of which many variants have been written down, and receiving various gifts in return.[37] The same custom is recorded for the Middle Ages. It does not seem very much like a religious practice, although it has its roots in religious or magical beliefs, but it shows a greater tenacity than any of the lofty religious ideas.

We return to the May bough which is often carried in such processions. The green branch with its newly developed leaves is the symbol of life and of the renewal of life, and there is no doubt that formerly the purpose of bringing in green branches and setting them up was to confer life and good luck. The custom persists, but its old significance has long been forgotten. The May bough is only a lovely decoration. Nowadays we find it at all rural festivals and at family festivals. The same custom prevailed in ancient Greece, though the name of the May bough varied. We have found it in several festivals, sometimes hung with fruits, flowers, and fillets like the modern Maypole. Sometimes the ancient May bough was as elaborately decorated as our Maypole. There is a graphic description of such a Maypole which was carried around the city of Thebes.[38] It was a laurel pole decorated with one large and many small balls of copper, purple fillets, and a saffron-colored garb. This Maypole was carried around at a festival of Apollo, with whom also the May bough is connected. I think it likely that the laurel became his holy tree because it was often used for May boughs.

Sometimes the May bough is simply called by the same name as the loaves which bring luck, hygieia (health, health-bringer), a name which proves that it was supposed to confer good fortune. In the Mysteries it was called bacchos, a name evidently connected with the role of Dionysus as a god of vegetation. Hence, it is customary to call by this name the bundles of branches tied together by fillets which appear in representations of Eleusinian scenes. In my opinion, the thyrsus which was carried by the maenads, a stick with a pine cone on its top and wound round with ivy and fillets, was just a May bough. We also find pine branches and stalks of the narthex plant in the hands of the maenads. In Sparta there was a cult of Artemis Korythalia, in whose honor lascivious dances were performed and to whose temple sucklings were carried. Her epithet is derived from another name of the May bough, korythale. It is said to have been the same as the eiresione. It was a laurel branch which was erected before a house when the boys arrived at the age of ephebes and when the girls married, just as in modern times the May bough is erected before a house for a wedding.

The May bough was carried in numerous processions. I may recall the thallophoroi--dignified old men carrying branches--represented on the Parthenon frieze. The suppliant who sought protection carried a branch wound with fillets, the hiketeria. Evidently the idea was that this branch made the suppliant sacred and protected him from violence. Finally, the crown of flowers which the Greeks wore at all sacrifices, at banquets, and at symposia and which the citizen who rose to speak in the popular assembly put on his head is another form of the May bough, and like the May bough it confers good luck and divine protection.

It may perhaps seem that I have wandered far from religion and have chiefly discussed folklore. But the distinction which has been made between religion and folklore since Christianity vanquished the pagan religions did not exist in antiquity. Scholars have been very busy discovering survivals of old magical and religious ideas in our rustic customs and beliefs. In ancient Greece such customs and beliefs were part of religion. Greek religion had much higher aspects, but it had not forsaken the simple old forms. They not only persisted among the people of the countryside, but they also found a place in the festivals and in the cults of the great gods.

These beliefs and customs are time honored and belong to the substratum of religion. They have not much to do with the higher aspects of religion, and they are for the most part magical in significance. They seem quite nonreligious in character, and very often they have changed into popular secular customs. This was not difficult in Greece, for, as we shall see later, the sacred and the secular were intermingled in a manner which is sometimes astonishing to us. But however profane these customs and beliefs may seem to be, their tenacity is extraordinary. Similar beliefs and customs occur everywhere in European folklore, and while the old gods and their cults were so completely ousted by a new religion that hardly a trace of them remains, the old rural customs and beliefs survived the change of religion through the Middle Ages to our own day.

The Religion Of Eleusis

A chapter on the religion of Eleusis is a natural sequel to the description of the rural customs and festivals,[39] for the Eleusinian Mysteries are the highest and finest bloom of Greek popular religion. Originally the Eleusinian Mysteries were a festival celebrated at the autumn sowing. This is proved by the testimony of Plutarch[40] and by their very near kinship to the Thesmophoria. Although it is acknowledged that the basis of the Eleusinian Mysteries is an old agrarian cult, this fact has been pushed into the background by the attempts to discover the secret rites of the Mysteries. They have been discussed repeatedly by scholars and laymen, and numerous hypotheses have been put forward, some of them intelligent, others fantastic, none of them certain or even probable. Such a question seems to cast an everlasting spell on mankind, for mankind wants to know the unknowable. But the silence imposed upon the mystae has been well kept.

We possess a knowledge of certain preliminary rites which were not so important that it was forbidden to speak of them. In regard to the central rites belonging to the grade of the epopteia, our knowledge extends only to the general outlines. We know that there were things said, things done, and things shown, but we do not know what these things were, and that is the essential point. The rites consisted, not in acts performed by the mystae, as modern scholars would have us believe, but in the seeing by the mystae of something which was shown to them. This is repeated again and again from the Homeric Hymn to Demeter onward, and it is proved by the very name of the highest grade, epopteia, but we do not know what it was that was shown. The name of the high priest, hierophantes, proves that his chief duty was to show some sacred things. The names of the family from which he was always taken, the Eumolpidae, and of its mythical ancestor, Eumolpos, prove that he was famous for his beautiful voice. He recited or sang something, but what it was we do not know. Words probably accompanied the showing, but the showing, not the words, was the chief and culminating act of the Mysteries. It should be kept well in mind that the highest mystery was something shown and seen. It may be added that the Mysteries were celebrated by night in the light of many torches, which added to their impressiveness.

The silence imposed upon the mystae has, as I said, been well kept. Only Christian authors, who paid no heed to the duty of silence, have given information concerning the central rites of the Mysteries. But their testimony is subject to the gravest doubts. In the first place, what did they know? Had they any firsthand knowledge? Had they themselves been initiated? Clement lived in Alexandria and the others in Asia or Africa. It is much more probable that what they related was only hearsay. Further, are they reliable? We should realize that their writings were polemics against the perversity of the heathens and that in polemics of this kind controversialists are not conscientious about the means they use if only they hit the mark. Ecclesiastical authors certainly did not trouble themselves much about truth and about such questions of fact as whether a given rite belonged to the Eleusinian or to some other Mysteries, if only they could succeed in impressing upon their hearers or readers a sense of the contemptibility of the Mysteries. The hearers and readers knew nothing for certain and were not able to control the suggestions made to them.