Nummits and Crummits,

Devonshire Customs, Characteristics, and Folk-lore

Sarah Hewett

First published in 1900.

This online edition was created and published by Global Grey on the 22nd June 2022.

Table of Contents

VII. Peculiar and Eccentric Devonians

Preface

This little book is made up of a few crumbs from the repositories of many Devonshire friends, to whom grateful thanks are tendered for their untiring helpfulness in supplying so much that is quaint and interesting.

The miscellaneous scraps here gathered shew but inadequately the humorous characteristics of our Devonshire folk, their dialect, and as some like to call it, “jargon,” as drawn by themselves. They illustrate what the people actually believe in, say, and do, and shew the general trend of their minds. Their belief in the supernatural is unbounded. Neither age, social position, nor culture makes much difference: one and all are more or less wedded to the superstitions, beliefs, and traditions of their ancestors.

Apologies are offered to any one whose “Crummits” have been appropriated without permission or acknowledgment.

It was impossible to say from whom they arrived, as hundreds of newspaper and other cuttings came to hand anonymously, and being very precious morsels were reproduced. To each and all contributors most grateful thanks are given.

SARAH HEWETT.

3 Blundell’s Crescent, Tiverton, Devon,

July, 1899.

I. Superstitions

I tell thee,

There’s not a pulse beats in the human frame

That is not governed by the stars above us.

The blood that fills our veins, in all its ebb

And flow, is swayed by them as certainly

As are the restless tides of the salt sea

By the resplendent moon; and at thy birth

Thy mother’s eye gazed not more steadfastly

On thee, than did the star that rules thy fate,

Showering upon thy head an influence

Malignant or benign.

ALL HALLOWE’EN SUPERSTITIONS.

I think I cannot do better than describe what actually took place at an old farm house, in the eighties, in South Devon.

I was invited to spend a few days with a family, consisting of a farmer, his wife, and seven grown-up sons and daughters. The farm was picturesquely situated on a south-western slope of the Haldon Hills, from whence extensive views of land and sea could be enjoyed.

Mary was the youngest and merriest of the family. She it was who acted as prime mover in all the fun, not that either of the others showed any reluctance to carry out her wildest suggestions. A brighter set of young folk it would be difficult to find, and it has seldom been my good fortune to meet their equals in high spirits and natural gentleness. Every one was thoroughly imbued with credulity in regard to omens and predictions.

Mary suggested that All Hallowe’en should be observed with due ceremony, as indeed it was. The amusements began with fortune-telling by cards, at which Maggie the eldest daughter was an adept. The fortunes were appraised as “not up to much,” and as no one crossed Maggie’s hand with a piece of silver, the cards were swept aside.

Then Jack, otherwise the family clown, brought in dishes of apples and nuts, bags of hemp seed, torn paper, large basins of water, scraps of lead, a melting ladle, large combs, small hand mirrors, and a printed sheet of capital letters, all of which were to be used as love-charms.

Just as the clock began to strike eleven, a move was made towards the fireplace, where from the bars of the grate Jack had already swept every vestige of ashes.

Simultaneously each girl laid a big hazel nut on the lowest bar of the grate, and sat silently watching the result. I noticed that perfect silence was religiously observed during each ceremony.

She, whose nut first blazed, would be the first to marry.

She, whose nut first cracked, would be jilted.

She, whose nut first jumped, would very soon start on a journey, but would never marry.

She, whose nut smouldered, would have sickness, disappointment in love, and perhaps die young.

After this, one of the girls took an apple, a comb, and a mirror, and retired to the brightest corner of the room, where she began to comb out her long tresses with her left hand and held an apple in the right, which she slowly ate. Her future husband was expected to look over her shoulder, revealing his face to her in the mirror. He did not, however, satisfy our curiosity by putting in an appearance.

Then one took a handful of torn paper and scattered it on the surface of a big basin of water, and after stirring vigorously, awaited developments. The number of pieces of paper which fell to the bottom indicated the number of years which would intervene before the operator’s marriage. In this case twenty-one fell, and as Jenny was now twenty-eight, Jack thought there was small chance for her to have an establishment of her own at forty-nine, so she had better resign herself to her fate, and be content to become the unappropriated blessing of the family, for, said he, “How could you, Jenny, at that advanced age, dare to don white satin and orange blossoms? No, my dear, your future is sealed.”

Then everybody insisted on Jack trying his luck, which he essayed to do by melting a few scraps of lead in the ladle and pouring it red hot into one of the basins of cold water. The letters formed, or the nearest approach to letters, at the bottom of the basin were supposed to be the initials of the future “ She.” The closest resemblance to letters which we could discover was an I, and an L. The question which now arose amid merry peals of laughter was to whom the initials I.L. could belong. Many names were mentioned and negatived as soon as suggested, Jack looking rather bashful, when from Jenny came the query—“Does not I stand for Ida, and L for Lang? Ida Lang is a very pretty name, and is owned by a very sweet girl.”

Jack gave Jenny a look which could easily be interpreted “I owe you one for that, Jenny ”—“ Oh! oh! Jack,” replied Jenny, “we are hoping that Ida Lang will not be an unappropriated blessing. She shall have my white satin and all the orange blossoms.” There was a good deal more of this sort of chaff, but no offence was taken by the good-natured Jack, and things swung along amicably.

Next came Tom to try his hap with a pair of scissors. Tom in silence separated the capital letters, each falling into the basin of water without being touched by the hand. When all were free they were stirred and left to settle. The initials of the future one, were supposed to float on the water. Alas! poor Tom! in his case fifteen letters presented themselves. Here again was food for fun and conjecture. Many suggestions were made. Tom, perhaps was going to be a Mormon, or perhaps he was going abroad and set up a harem, and all sorts of other absurd theories. Mary at last came to the rescue, “Oh, I know,” said she, “take G and M out and there you have Gertrude Morley, then tack all the rest on to the end of the name, and there you have certain degrees won by Gertrude at the ’Varsity. Gertrude is a Newnham student. Last autumn in the long vacation there was a young woman of that strain dodging across the hills, and on one occasion wh6n she saw our Tom cantering towards her, her bike became fractious instanter, and poor innocent Tom had to dismount, tie Highflyer to a gate-post and assist the distressed biker. Of course, Tom couldn’t help himself and had to lead Highflyer up the hill and push the bike too.” Alas poor Tom! Then turning to her mother she explained that Tom was about to present her with a new daughter in the form of a Newnham girl so vastly clever, that she used up all the alphabet to shew how clever she was and the heaps of degrees she took, &c., &c. “ I say, Tom, do you think Gertrude Morley, B.A., M.D., M.G.L.Q.R., will like taking my place in the house work, and be able to cry chuggie, chuggie, chuggie, every morning to the dear little piggy-wiggies; perhaps though, instead of giving them barley-meal and milk, she’ll sit them all in a row, in the bottom of the trough, and teach ’em Latin and Greek don’t-cher-know; eh, Tom dear?”

Heedless of this affectionate raillery, everything drifted along smoothly, and four dishes of water were brought in and placed severally in three corners of the room, and the fourth, emptied of its contents, was placed in the fourth corner. Then four blind-folded operators were led into the room and placed back to back in its centre, the lights having been previously extinguished. Then all four fell on their knees and each crept at discretion to any, or all to the same, corner.

The empty dish portended celibacy or poverty. The dish of clean water, that the future one would never before have married. The dish of dirty water, that the future spouse would be a widow or widower. The dish of water with pebbles at the bottom, riches and honour.

Now the crucial movement was at hand. Each girl took possession of a big handful of hempseed. The front door was thrown wide open and securely fastened back to prevent the possibility of its being accidentally closed; the girls stood without. As the clock gave the first stroke of twelve off they started each in a different direction across the lawn, shouting:

Hempseed I sow,

Hempseed I throw,

He that’s my true-love,

Come after me and mow!

The spirits of the future ones were expected to be beyond the shrubs ready to rush after the sowers, and unhappy would have been the maiden, who could not get over the threshold before the scythe of the reaper caught her. All the girls reached the hall unharmed: little Mary, looking a bit scared, said, as she wound her arms around me: “Oh, wasn’t I just about startled? indeed, I was, for I thought I saw Dick Harvey right in front of me as I turned to come back, holding a bright new sickle over his head.” I felt the child tremble, and then I enquired, “Who is Dick Harvey?” “Oh, nobody in particular, don’t tell.” Of course I have not told till now.

After supper we retired for the night. The next morning the girls told me, that sometimes they placed tiny scraps of bridecake, wrapped in tissue paper, under their pillows at night, hoping they would dream of “him:” at other times made a “dumb cake,” and gave me a recipe for making one, which I append.

Jenny told me too, that one evening when visiting friends at Paignton, one of the party saw for the first time the new moon: she called all the young folk out on the balcony requesting each to bring a small handmirror, to turn their back to the moon, and holding up the mirrors to catch the reflection of the moon. As many reflections as were cast on the glass, so many years would pass before the marriage of the holder took place. One charming girl of the party told me: “ I had three moons. Fancy that, my dear, and you know how very old I am now, and have three years of weary waiting yet.”

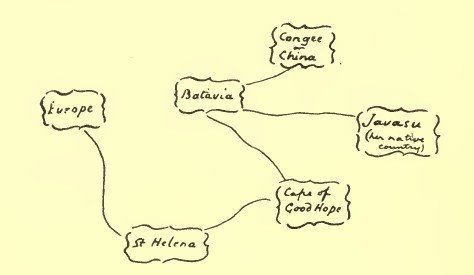

That delightful family is broken up. The parents are both dead, and the children are scattered to the ends of the earth. Not one is left in England. Each member has carried the old songs, the old dialect, and the old folk-lore of the old country, into new homes, in new countries, and there in time a new generation will spring up, who will be taught the traditions of the past; and perhaps the incidents of that happy All Hallowe’en, spent amidst the uplands of dear old Devon, will form one of the pleasantest narrations.

Poor Dick Harvey never came to claim little Mary, for, very soon after that happy evening, news came of a great storm, and Dick, who was first officer of the ss. Petrel, was lost with all hands in mid Atlantic.

Everywhere throughout the length and breadth of Great Britain, the festive and fortune-telling practices of this evening are observed in almost identical fashion. Gray, in The. Spell, tells us that—

Two hazel-nuts I threw into the fire,

And to each nut I gave a sweetheart’s name.

This, with the loudest bounce, me sore amazed,

That, in a flame of brightest colour blazed:

As blazed the nut so may thy passion grow,

For ’twas thy nut that did so brightly glow.”

Then we have in Nut burning on All Hallow eve, by Charles Graydon, the following—

These glowing nuts are emblems true,

Of what in human life we view;

The ill-matched couple fret and fume,.

And thus in strife themselves consume;

Or from each other wildly start,

And with a noise for ever part.

But see the happy, happy pair,

Of genuine love and truth sincere

With mutual fondness while they burn,

Still to each other kindly turn;

And as the vital sparks decay,

Together gently sink away:

Till life’s fierce ordeal being past,

Their mingled ashes rest at last.

Burns, too, contributes a long poem on “ Halloween,” which gives us an insight into the manners and traditions of the peasantry in the West of Scotland in his time.

The old goodwife’s well hoarded nuts

Are round and round divided:

And many lads’ and lasses’ fates

Are there that night decided:

Some kindle, couthie, side by side

And burn together trimly;

Some start away with saucy pride

And jump out o’er the chimney—

Full high that night.

RECIPE FOR MAKING A DUMB CAKE.

In the preparation of a dumb cake, if perfection be desired, it is imperative to observe strict silence, and to follow these instructions closely.

Let any number of unmarried ladies each take a handful of wheaten flour, and place it on a sheet of white paper, then sprinkle it with as much salt as can be held between the finger and thumb; then, one must put as much clear spring-water as will make it into dough, which being done, each of the party must roll it up, and spread it thin and broad, and each maid must, at some distance apart, make the first letters of their Christian and surname with a large new pin, towards the end of the cake; if more Christian-names than one, the first letter of each one must be made. Then set the cake before the fire, and each girl must sit down in a chair, &s far from the fire as the room will admit, not speaking a word all the time. This must be done between eleven and twelve o’clock at night. Each person in rotation must turn the cake once, and five minutes after midnight the husband of her who is to be wed first will appear and lay his hand upon that part of the cake bearing her initials.—From the Norwood Gipsy Fortune-teller.

If the cake be eaten, strict silence must be observed from the moment a slice is cut. The person walks backwards from the room, up the stairs, and after undressing goes into bed, still backwards. Stumbling and giggling are inadmissible. It is presumed that happy dreams of “the loved one” will occupy the hours of slumber.

OMENS AND DEATH TOKENS.

Addison says, “We suffer as much from trifling accidents as from real evils. I have known the shooting of a star spoil a night’s rest, and have seen a man in love grow pale and lose his appetite upon the plucking of a merrythought. A screech-owl at midnight has alarmed a family more than a band of robbers; nay, the voice of a cricket has struck more terror than the roaring of a lion. There is nothing so inconsiderable which may not appear dreadful to an imagination that is filled with omens and prognostications. A rusty nail or a crooked pin shoot up into prodigies.”

Belief in omens is not confined to the simple and uneducated, but permeate every social grade.

Omens are said to be “ the poetry of history.” Mary de Medici saw, in a dream, the brilliants of her crown change into pearls — symbols of tears and mourning. The Stuart monarchs held that their sorrows and misfortunes were foretokened. The learned Earl of Roscommon and Dr. Johnson were believers in spectres and supernatural agencies.

The mountaineer makes the natural phenomena which daily present themselves to him foretokens of weal or woe. Dwellers in low-lying countries, too, find signs in their surroundings to distress and disturb their peace of mind. Each is continually inviting bugbears to harass and worry him.

There is a strong belief that the robin, raven, magpie, owl, and a nameless white bird, by the manner of their flight, and other peculiarities of action, foretell the approaching dissolution of some member of the household which they visit. A robin sitting near a window, uttering a plaintive weep,—weep,—weep,— presages sickness and death; if he flies into an occupied bedroom, then, death is near at hand.

A remarkable instance of credulity in robin-lore came to my notice in 1891. The following was told me by an educated lady, whose temperament is in no way morbid or hysterical; but is in herself bright, cheerful, and religious. The sight of a robin carries her memory back to some of the saddest days of her life. Here is her story:—

“In 1848 I was staying with my grandparents at Ashburton, in Devonshire. My grandmother, having a severe cold, went early to bed, and the weather being oppressively hot, the window was left open. Presently a robin, dishevelled and melancholy, flew into the room and perched on the towel-rail. No amount of persuasion could dislodge him, and at last all efforts to ejedt him were abandoned. He continued his sad weep,—weep,—weep,—for at least an hour, when he quietly flew out of the window. That night grannie died. Again, in 1851, a robin, just as unhappy and forlorn as the former one, flew into my father’s bedroom, exhibiting every sign of dejection. Nor would he be easily driven off, but sought the tester of the bed, where he continued his weep,— weep,—weep. That night my father died.

“Again, in the autumn of 1884, while on a visit to Dawlish with my husband and children, we often took our books and work into the garden. One evening, as usual, we were in the summer-house, the children playing noisily, when a robin flew into their midst, and hopped on the table, finally perching himself on the handle of my work-basket. A more pitiable dejected little birdie could not be imagined, his feathers were ruffled and touselled, and both wings drooped to his feet. There he sat, uttering his dolorous weep,— weep,—weep,—for several minutes; when we rose to go into the house he followed, sometimes fluttering along before us in the path, at others flitting from bush to bush close at our side. Even after we had closed the window we heard him on the shrubs outside, still pathetically uttering his doleful weep,— weep,—weep. The next morning my dear husband, who had gone along the Strand for a stroll while I dressed the children for a walk, dropped suddenly dead, and was brought home within a quarter of an hour after leaving the house. Can you wonder at my having a dread of a visit from a robin, after these pitiful experiences?”

THE WHITE BIRD OF THE OXENHAMS.

There exists in the family of the Oxenhams a tradition that a bird with a white breast is always seen fluttering over their beds, previous to the death of a member of their family.

The Oxenhams were an ancient family of considerable influence and importance, occupying and possessing large and valuable properties in the vicinity of Okehampton. But the glory of the house has departed, though there are still branches of it at the present time residing at South Tawton, who still retain the tradition of the white bird. Very recently (1892) an Oxenham has said that the bird appeared to him, and very shortly afterwards his father died. It therefore appears that this bird of ill-omen is a legacy in perpetuity, bequeathed at an ill-starred moment to his descendants by some unfortunate ancestor. There are numerous records of the appearance of this bird prior to 1700, but the most interesting is that which describes its visit to Sir James Oxenham, on the eve of his daughter Margaret’s nuptials.

The full text of a poem giving details of the appearance of the apparition, is given in “ The Report and Transactions of the Devonshire Association for the Advancement of Science, Literature, and Art,” for 1896, which was sent by Miss E. Gibbs, of South Tawton, who copied it from the housekeeper’s commonplace book at Oxenham House.

For those who may be unable to procure the whole of the poem, I select one or two stanzas which may be interesting.

Where lofty hills in grandeur meet,

And Taw meandering flows,

There is a calm and sweet retreat

Where once a mansion rose.

There dwelt Sir James of Oxenham,

A brave and liberal lord:

Benighted travellers never came

Unwelcome to his board.

Here it goes on to say that Margaret was sole heiress to his property; she was wooed by one Bertram, who from a blow on the head became an imbecile. Margaret’s grief was great, but “consoling time healed the heart with anguish grieved,” and “soft vermilion of her cheek again begins to flow.”

Then John the Knight of Roxamcave

Sought her fair hand to gain:

And he was handsome, young, and brave—

How could he plead in vain?

He fondly pressed his Margaret

To fix their nuptial day,

And on its joyful eve they met

With friends and kinsfolk gay.

****

How happy was Sir James that night,

Unburdened of his care.

For he believed, with fond delight,

That heaven had heard his prayer.

****

Then up he rose, with joy elate,

To speak unto Sir John,

And rapt desire, outspeeding fate,

In thought he called him son.

But while the dear unpractised word

Was forming on his tongue,

He saw a silvery-breasted bird

Fly o’er the festive throng.

****

Now John, and Margaret, and her sire,

With many a dame and knight,

Ranged round the altar, heard the friar

Begin the holy rite.

When Margaret, with terrific screams,

Made all with horror start.

Oh, heavens! her blood in torrents streamed,

A dagger’s in her heart.

Behind stood Bertram, who then drew

Away the reeking blade;

And frantically laughed to view

The life-blood of his maid.

“Now marry me, proud maid!” he cried,

“Thy blood with mine shall wed.”

Then dashed the dagger in his side,

And on the ground fell dead.

Poor Margaret, too, grows cold with death,

And round her, hovering, flies

The phantom bird for her last breath,

To bear it to the skies.

TRADITIONS OF THE COURTENAYS OF POWDERHAM.

The countess Isabella is accredited with having planted the oaks of Wistman’s Wood on Dartmoor. She, too, it was, who met a man on Bickleigh Hill, near Tiverton, carrying a basket containing seven of his baby children, to whom he intended to give “ a swim in the river Exe at Bickleigh Bridge.” On being asked by her what he was carrying, he replied, “ Puppies not worth rearing.” Presently he confessed that his wife had given him seven sons at a birth, and fearing the lack of food and raiment, he had determined to drown them. The countess adopted them, and provided for their upbringing out of the proceeds of her estates at Tiverton and Chumleigh.

THE DEATH-WATCH.

One often hears issuing from the rafters and woodwork of old houses sounds resembling the ticking of a watch. These clickings are produced by a small insect known as the “ Death-Watch.”

By nervous persons they are considered omens of death.

Mrs. Hagland, a laundress, living at Tiverton, came to me one morning in great distress of mind, and her simple story will give a better insight into the feelings of the superstitious than any thing I can say. I give verbatim her account of a very unhappy experience—

“I be zure zom’thing is gwaine tu ’appen til me, or mine, for all last night I kep’ on hearing of the Death-Watch, aticking, ticking, ticking, ess, he kep’ on ticking till he drawved me most mazed. He made me think of my poar bwoy Bill whot’s out to zay, ’e tha’ bin gone now for til or dree yer; I du zim ’tez a brave while ago I zeed ’n, but there God Almighty ’th tuked kear aw’n zo var and I ’opes as how He will ’et. I a’n’t ahad ide-nor-tide aw’n zince he went away and I du zim tez a longful time agone that I zeed’n. Well, as I wuz azaying of, I yeard that Death-Watch aclicking all dru the night and du trubble me dreffel bad. Gi’th me the heart ache and I can’t get no rest for thinkind aw’n; ’tez all day and ivvry day and all night tu. A mawther’s heart is a sorrowful thing tu car about, when her only cheel is zo var away, and out tu zay tu. I’ve a yerd the DeathWatch avore, and then my mawther died perty quick afterwards, but he diddent tickee zo ’ard and zo dismal-like as he did last night. It zimmdd to me, as how he zed, ‘tick! tick! tick! tick! wake up, Mawther! I be drownded! I be drownded!’ Ah! Lord-a-massy! if he be a drownded ’twill break my heart. What duee think mum?”

Poor soul, she went away, crying bitterly. Bill never came back, and now she has gone to her rest, where there will be no more wakeful nights, or dread born of the love-calls of a common insect.

Swift ridiculed the foolish fancy of predicting death in this way, but ridicule, be it never so strong, does not kill belief in the supernatural.

A wood-worm

That lies in old wood, like a hare in her form,

With teeth or with claws it will bite, or will scratch;

And chambermaids christen this worm a death-watch

Because like a watch it always cries click;

Then woe be to those in the house that be sick,

For, sure as a gun, they will give up the ghost.

If the maggot cries click when it scratches the post

But a kettle of scalding hot water ejected,

Infallibly cures the timber affected.

The omen is broken, the danger is over;

The maggot will die, the sick will recover.

DEATH TOKENS.

If a corpse retains heat and flexibility it is said that others of the same family will die before the year is out.

If a sheet or tablecloth is returned from the laundry with a square fold in the centre, so, it is said to portend the death of the master or mistress of the house.

If letters cross in the post it is a sign of death.

SUPERSTITIONS ATTACHED TO THE MARRIAGE CEREMONY.

There are many superstitious customs attached to the marriage ceremony, some of which are supposed to endow the pair with blessings and an abundant share of the good things of life, while others bring only misfortune and disquietude.

Witches and pixies alas, are workers of evil, and beset the path of the bride and bridegroom to and from the church, plying their wicked tricks to the detriment of the unhappy pair. The days of the week, too, on which the ceremony is performed, influence their future, as the following lines testify:

Monday for wealth,

Tuesday for health,

Wednesday is the best day of all,

Thursday for crosses,

Friday for losses,

Saturday no luck at all.

Sunday is an exceptionally fortunate day upon which to enter the holy state.

One often hears:

“Happy is the bride that the sun shines upon.”

Among the customs bringing good luck to the pair, are pelting them with rice as they leave the church after the ceremony, and throwing old slippers at them, too, as they leave the house for the honeymoon.

Happiness can be insured by observing certain practices which have been in vogue for many centuries, as for example: it is necessary to carry sprigs of rue and rosemary and a few cloves of garlic in the pocket, to enhance the felicity of the pair. The bride also should carry a small packet of bread and cheese in her pocket to give to the first woman or girl she meets after leaving the church.

Dire calamities will overtake the couple if either of these cherished practices are omitted, though the perfume of garlic and rue added to the wedding bouquets seems incongruous.

Now follow the unfortunate omens and events attached to this momentous occasion. Should a raven hover over their path, a cat, dog, or hare pass between them, or should they encounter a toad, frog, or other reptile, then terrible misfortunes will follow them for all time. These creatures are supposed to be the embodiment of pixies, witches, and every species of evil spirit. Even his satanic majesty does not object to assume the form of an animal, to enable him to work certain ill on their future lives, and to assist in contributing his share to their distress.

In Devon, when a wife is of stronger will than her husband, the people say, “ Aw ess, the grey mare in thickee ’ouze is the better ’oss,” and ascribe her masterfulness to her having visited and drank of the water of the well of St. Keyne, in Cornwall.

DIVINATION BY THE BIBLE.

A person wishing to know whether success or failure is to attend his future, should open the Bible at the forty-ninth chapter of Genesis, begin with the third verse and end with the twenty-seventh: the verse he first chooses will be typical of his future fate, character, and success in life.

Another method practised by country folk on almost every occasion, is to open the Bible at random, and the words which first present themselves decides the future lot of the enquirer.

In Devonshire, many persons when they have lost anything, and suspect it to have been stolen, take the front door key of their dwelling, and, in order to find out the thief, tie this key to the Bible, placing it very carefully on the eighteenth verse of the fiftieth Psalm. (“When thou sawest a thief, then thou consentedst with him, and hast been partaker with adulterers.”) Two persons must then hold the book by the bow of the key, and first repeat the name of the suspected thief, and then the verse from the Psalm. If the Bible moves, the suspected person is considered guilty; if it does not move, innocent.

CLOVER AND ASH-LEAF SUPERSTITION.

An even leaved ash and a four leaved clover

Are certain to bring to me my true love

Before the day is over.

An even leaved ash and a four leaved clover are beneficent attractors of the opposite sex, for if one finds an even leaved ash and holds it flat between both hands, and repeats softly,

“With this even leaved ash between my hands

The first I meet will be my dear man.”

then placing it in the palm of the gloved right hand, say,

“This placed in my glove

Will bring my own true love.”

then remove it to the bosom and whisper,

“This even leaved ash in my bosom

Will give me, in the first man I meet

My true husband.”

ABOUT SALT

Salt, in country districts, is held as a sacred article, and the vessel used to contain it is considered hallowed and looked upon as a valuable possession. Dire calamities follow on spilling salt, and a charm is used to counteract the dread consequences. An old nurse once told me that if a plate of salt be placed on the breast of a corpse, it would help the dead to rest peacefully, as it kept evil spirits from tormenting the soul on its journey through the dark valley.

An old Devonshire friend has sent me the following lines, which he is in the habit of repeating when small matters go wrong in his household. I believe they were written by the poet Gay, from whom he must have learnt them when a child.

Alas, you know the cause too well!

The salt is spilt: to me it fell;

Then, to contribute to my loss,

My knife and fork were laid across:

On Friday, too, the day I dread.

Would I were safe at home in bed!

Last night (I vow to heaven ’tis true)

Bounce from the fire a coffin flew.

Next post some fatal news shall tell

God send my absent friends are well!

ONEIROMANCY.

Oneiromancy is the art of interpreting dreams. This kind of divination is still in use among the masses, and has been practised from the most remote ages. In rural districts there are to be found ancient dames whose interpretations of dreams are looked upon with reverence, and are a source of revenue to the old women.

At breakfast, it is not uncommon for members of a family to narrate their dreams, and seek the elucidation thereof.

“A dream is an ill-arranged action of the thinking faculties during a state of partial sleep, and is but a momentary impression, perfectly natural in its operation; the state of mind which causes it being produced by temporary functional derangement.”

If I dream of water pure,

Before the coming morn,

’Tis a sign I shall be poor,

And unto wealth not born.

If I dream of tasting beer,

Middling then will be my cheer—

Chequered with the good and bad,

Sometimes joyful, sometimes sad;

But should I dream of drinking wine,

Wealth and pleasure will be mine.

The stronger the drink, the better the cheer,

Dreams of my destiny appear.

The belief that dreams are indicative or symbolical of coming events is very common among the masses. Some persons look upon dreams as absolutely true mediums of revealing the secrets of futurity.

The following few examples shew “the stuff which dreams are made of.”

Ass. To dream one sees an ass labouring under a heavy burden, indicates that one will by diligent application to business amass a fortune.

Absent ones. To dream of these ill, or in trouble, shows they are in danger; if well, it is a sign they are prosperous.

Angels. A happy dream, showing peace at home, and a good understanding with your friends.

Baby. If you dream of holding a baby in your arms it signifies trouble.

Bells. If you hear them ring it is a good sign, foretelling luck in business and speedy marriage.

Bees. That you see a swarm of bees signifies you will be wise and highly respected. If they disturb or sting you, you will lose friends, and your sweetheart will abandon you.

Carriage. If you dream that you are shut up in a carriage and cannot get out, it shows that your false friends are scandalizing you; and you will suffer much at their hands.

Cats. Dreaming of cats shews that your female friend are treacherous.

Cards. If you dream you are playing cards it signifies that you will shortly be married.

Dancing. This is fortunate. You will gain riches, honour, and many friends. Your life will be long, happy, and prosperous.

The Dead. To dream of the dead brings news of the living.

Ducks. To see them in a pond swimming about is an omen of good luck.

Eggs. That you are eating eggs shews you will be delivered from great tribulation. That you break them when raw, shews loss of friends and fortune.

Empty Vessels shew that your life will be one of toil and privation.

Eating. Portends sickness and death.

Fish. To dream of fish shows that you will have an abundance of wealth and good things. Also that you will be successful in love.

Fire. To dream of fire shews that you will have hasty news.

Flowers. Always a good dream; is a sure sign of joy, success and prosperity.

Garden. To dream of being in a beautiful garden shews you will be rich and prosperous in love.

Glass. Broken glass foretells quarrels and family strife.

Gold; To dream of gold portends riches.

Hares. To dream of these implies great trouble in pecuniary matters and sickness.

Horses. Shews that your life will be long and happy. If kicked by a horse you will have a long and severe illness, and heavy misfortune.

Ivy. A sign that your friendships are true.

Inn. To dream that you are staying at an inn is a most favourable one. It shews that you will inherit a large fortune, be successful in all your undertakings, and will enjoy much happiness.

Jackdaw. Beware of danger and evil disposed persons.

Journey. If you are about to take one in your dream, you will meet with reverse of fortune.

Knives are always omens of some evil about to happen.

Kiss. To dream that some one is kissing you, is a sure sign that you are being deceived. To dream that you are kissing some one whom you love is a sign that your love is not reciprocated.

Larks. To dream of these birds is a good sign, as it denotes that you will overcome all difficulties that may come in your way, and you will speedily rise to a good position.

Lightning without thunder is one of the very luckiest dreams. To lovers it means happiness; to farmers, good crops; and to sailors, prosperous voyages.

Mad Dogs. In dreams these are omens of success. Magpies. That you will soon be married.

Nightingales. Nightingales singing are indicative of bright days coming and a release from all troubles and anxieties.

Nuts. Indicate the receipt of money.

Oats. Are lucky omens of success.

Onions. If you dream you are eating them you will find much money.

Pall. One over a coffin is prophetic of a wedding dress.

Parcel. If you carry one you should receive a foreign letter.

Quarrels. If you dream of them it is a sign that you will soon be very profitably engaged in a business matter.

Rain. Is an omen of misfortune.

Rats. Prophesy enemies near at hand.

Teeth. To dream of, are the most unlucky of all things. If they fall out it signifies much sickness, if they all drop from the gums, death.

Ships. Sailing in clear water are favourable omens, but if the water be murky, most unfavourable.

Silver Coins. Picking them up, unless there be gold with them, is significant of impecuniosity.

Ugliness. If you see yourself reflected as very ugly it is an omen of success.

Umbrellas. If you lose them it signifies losses in business.

Valentine. Dreaming of receiving one is a bad sign, illness and trouble will soon be upon you.

Violin. If you are playing on one in your dream, it denotes speedy marriage; unless a string breaks, then you will not marry at all.

Water. Dreaming of water, if it be clear will bring good news, if dirty, bad news is at hand.

Wedding. One dreamed of signifies a funeral.

Yachting in clear water on a sunny day is prophetic of very great happiness.

Yew-trees. You will hear of the death of an aged person in whom you have a vested interest.

In Mackay’s Popular Delusions, 1869, occurs the following passage, which seems too good to omit.

“Dreams, say all the wiseacres, are to be interpreted by contraries. Thus, if you dream of filth, you will acquire something valuable; if of gold and silver, you run the risk of being without either; if of many friends, you will be persecuted by many enemies. The rule does not, however, hold good in all cases. It is fortunate to dream of little pigs, but unfortunate to dream of big bullocks. If you dream of fire you will have hasty news from a far country; if of vermin, you will have sickness in your family; if of serpents, your friends will become your bitterest enemies; if you are wallowing up to your neck in mud and mire, you will be most fortunate in all your undertakings. Clear water is a sign of grief; and great troubles, distress, and perplexity are predicted if you dream you are standing naked in the public streets and know not where to turn for a garment to shield you from the gaze of the multitude.”

To dream of walking in a field,

Where new-born roses odours yield;

If any of them you do pluck,

It shews in love much happy luck.

To dream of mountains, hills, or rocks,

Does signify flouts, scoffs, and mocks;

Their pains in passing ever shew

That she whom you love, loves not you.

Dreams of joy and pleasant jests,

Dancing, merriment, and feasts,

Or any dream of recreation

Signifies love’s declaration.

Dreams full of horror and confusion

Ending merrily in conclusion,

Shews storms of love are overblown,

And after sorrow joy shall come.

From Forty’s Norwood Gipsy's Fortune-teller.

ST. MARK’S EVE

Repair to the nearest churchyard as the clock strikes twelve, and take from a grave on the south side of the church three tufts of grass, and on going to bed place them under your pillow, repeating earnestly three several times,

The eve of St. Mark by prediction is blest, Set therefore my hopes and my fears all to rest: Let me know my fate, whether weal or woe; Whether my rank’s to be high or low;

Whether to live single or to be a bride, And the destiny my star doth provide.

Should you have no dream that night, you will be single and miserable all your life. If you dream of thunder and lightning, your life will be one of great difficulty and sorrow.

ST. JOHN’S EVE

Make a new pincushion of the very best black silk velvet (none other will do), and on one side stick your name in the very smallest pins you can buy; on the other side make a cross with some large pins, and surround it with a circle. Put this into your left-foot stocking when you take it off at night, and hang it up at the foot of the bed. All your future life will pass before you in a dream.—Mackay’s Popular Delusions.

THE LEGEND OF ST. DECUMAN

Happy Decuman was born of a good family in the western part of Wales, of parents strict observers of the Christian religion. He, after he had passed his childhood at home, as he advanced in years, was of a very good disposition; and at length crossed the Severn unknown to all his acquaintance, especially to his relations, and to those who seemed to be more nearly concerned for his welfare; trusting in Christ alone for his protection. But not to mention anything more, he paid no freight and had no ship. This good man relying upon the mercy of God, not doubting but that He would protect him, bound shrubs together, which he found growing by the sea-side, and making use of such a vehicle committed himself to the ocean. Being by divine providence directed, he was carried to the opposite shore, near Dart’s Castle.

There was in that part of the country in which he landed, a desert place (presumably Exmoor) beset with shrubs and briars, which were very long and large, and by the hollowness of the vathes was wonderfully separated. This place pleased him much: changing his native country for a sort of exile, the luxury of a palace for the dens of a desert. There he began to dwell and to live upon roots and herbs, leading the life of a hermit, and by such government in the above-mentioned desert, he lived many years.

It is said also that he had a cow, by the milk of which he was more kept alive than nourished, especially upon certain festival days. When the fore[1] happy Decuman had flourished in virtues of every kind, a certain man, but he, a man of Belial, enjoying the holiness of so great a Father, drunk with passion, rushed on, and in a brutish manner met him: and as he spoke and prayed, he sent the Saint to Heaven by cutting off his head.

But this also is not to be passed by in silence, for when he was beheaded with a certain sort of crooked hook, as ’tis reported, his body rose itself up and begun with its dangling arms to carry his head from the place where it was cut off even to a very clear well of water, in which he washed his head with his own hands as he was used to do; which well, even to this day, in memory and reverence of the Saint, is called the pleasant well of St. Decuman, useful and well for the inhabitants to drink. In which place his head together with his body being afterwards sought Father Cressy, in his Church History, Ixxi, places his martyrdom in the reign of King Ina, a.d. 706, from the authority of Capgrave and the English Martyrology.

THE MISTLETOE CURSE

Mistletoe, a parasite chiefly found on oak and apple trees, was held in great esteem by the Druids, who affirmed that miraculous cures were effected by its means. They ascribed to it a divine origin, and bestowed upon it the name “ Curer-of-all-ills.”

The trees on which it grew, and the birds visiting their branches, were considered sacred, and were thought to be the messengers of the gods. When mistletoe was required in the performance of their sacred offices, great ceremony was observed in separating it from the limbs on which it grew; the priests using a golden sickle for the purpose.

Devonians believe that their county was cursed by these ancient religious fathers, and the mistletoe forbidden by them to grow in it. Why this curse was laid on Devon there is no record to show. A gentleman possessed an orchard, one half of which is in Devon, and the other in Somersetshire, the division of the counties being marked by a deep ditch. On the Devon side the apple-trees are free, while on the Somerset side this parasite grows in abundance. He has tried in vain to cultivate it on trees in the banned county.

LEGEND OF THE GLASTONBURY THORN

When Joseph of Arimathea came to England he visited Glastonbury, so the legend says, and being wearied with the long climb up the hill, halted and leaned on his stout black-thorn staff. The stick sank into the soft mud on the wayside, took root, grew, and bloomed on Old Christmas Eve. There it stands to this day and always repeats the operation each successive year. There is also a sacred spring at its roots, in which thousands of persons came to bathe on Old Christmas Eve, a.d. 1751.

This marvellous thorn has a rival in the grounds of Clooneaven House, at Lynmouth, N. Devon, where the little bush bursts into vigorous bloom for a few hours at Christmastide. Very soon its flowers fade and the plant assumes its normal condition until the following spring, when it puts on its pretty green dress like the rest of its species.

THE COW GHOST

At a hamlet near the parish of South Tawton, a small town on the borders of Dartmoor, there is an interesting story told of a ghost which assumes the form of a remarkably handsome Guernsey Cow, and appears at midnight promenading to and fro under the spreading branches of an avenue of elm trees. It is said that a lady having done some terrible deed of darkness was transformed into a cow and condemned to walk nightly in this avenue for seventy times seventy years, bellowing frantically in token of the agonies experienced by this unhappy creature during her long term of punishment.

THE CHAGFORD PIXIES

As a gentleman, late at night, was driving across the moor to Chagford, a village in mid-Devon, he was startled by the merry tinkle of tiny bells. Lights appeared in the meadows close at hand as of thousands of glow-worms shedding their luminous rays on every leaflet, while an innumerable company of small people tripped joyously to the sportive music. Every movement of this assemblage of fairies was distinctly seen by him. He reined in his horse, and watched for a considerable time their merry antics. He sat motionless, the better to catch the spirit of the sportive scene. The sward was crowded with myriads of sprites, some waving garlands of tiny wild flowers, roses and blue bells, others joining in the dance, while not a few bestrode the slender stalks of tall grasses, which scarcely bent beneath their feathery weight. All went merrily till the shrill crow of chanticleer rang out on the midnight air, when suddenly darkness fell and the gorgeous scene with its fantastically attired crowd vanished from the wayfarer’s sight.

The villagers assert that on peaceful nights they often hear the echoes of delightful music and the tripping patter of tiny feet issuing from the meadows and hill sides.

By wells and rills, in meadows green

We nightly dance our heyday guise,

And to our fairy king and queen

We chant our moonlight minstrelsies,

When larks ’gin sing,

Away we fling,

And babes new-born steal as we go;

And elf in bed,

We leave instead,

And wend us laughing, ho! ho! ho!

THE GHOST OF THE BLACK-DOG

A man having to walk from Princetown to Plymouth took the road which crosses Roborough Down. He started at four o’clock from the Duchy Hotel, and as he walked at a good swinging pace, hoped to cover the sixteen miles in about three hours and a half. It was a lovely evening in December, cold and frosty, the stars and a bright moon giving enough light to enable him to see the roadway distinctly zigzagged across the moor. Not a friendly pony or a quiet Neddy crossed his path as he strode merrily onward whistling as he went. After a while the desolation of the scene seemed to strike him, and he felt terribly alone among the boulders and huge masses of gorse which hemmed him in. On, on he pressed, till he came to a village where a wayside inn tempted him to rest awhile and have just one nip of something “short ” to keep his spirits up.

Passing the reservoir beds, he came out on an open piece of road, with a pine copse on his right. Just then he fancied he heard the pit-pat of feet gaining upon him. Thinking it was a pedestrian bound for Plymouth, he turned to accost his fellow traveller, but there was no one visible, nor were any footfalls then audible. Immediately on resuming his walk, pit-pat, pit-pat, fell the echoes of feet again. And suddenly there appeared close to his right side an enormous dog, neither mastiff or bloodhound, but what seemed to him to be a Newfoundland of immense size. Dogs were always fond of him, and he of them, so he took no heed of this (to him) lovely canine specimen. Presently he spoke to him. “ Well, doggie, what a beauty you are: how far are you going? ” at the same time lifting his hand to pat him. Great was the man’s astonishment to find no resisting substance, though the form was certainly there, for his hand passed right through the seeming body of the animal. “ Hulloh! what’s this? ” said the bewildered traveller. As he spoke the great glassy eyes gazed at him; then the beast yawned, and from his throat issued a stream of sulphurous breath. Well, thought the man, I am in for it now! I’ll trudge on as fast as legs can carry me, without letting this queer customer think I am afraid of him. With heart beating madly and feet actually flying over the stony way, he hurried down the hill, the dog never for a moment leaving him, or slackening his speed. They soon reached a crossway, not far from the fortifications. When, suddenly the man was startled by a loud report, followed by a blinding flash, as of lightning, which struck him senseless to the ground. At daybreak, he was found by the driver of the mail-cart, lying in the ditch at the roadside in an unconscious state. Tradition says, that a foul murder was many years ago committed at this spot, and the vi6tim’s dog is doomed to traverse this road and kill every man he encounters, until the perpetrator of the deed has perished by his instrumentality.

There are similar legends of the doings of the Black Dog throughout the county, and many wayside public houses have “The Black Dog” for a sign.

SUPERSTITIONS ATTACHED TO CHURCH BELLS

In ancient times church bells were anointed with holy oil, exorcised, and blessed by the bishop, from a belief that when these ceremonies had been performed, they had the power to drive the devil out of the air, to calm tempests, protect from lightning, and keep away the plague.

The passing bell was anciently rung to bespeak the prayers of all Christian people for a soul just departing, and to drive away the evil spirit who stood at the bed’s foot to hinder its passage to the other world.

Men’s death I tell by doleful knell,

Lightning and thunder I break asunder,

The winds so fierce I do disperse,

Men’s cruel rage I do assuage.

A very frequent inscription on church bells in the fifteenth century, was voce mea viva depells cunta nociva.

This is a proof of the belief that demons were frightened away by the sound of bells. In a Cornish belfry the following rhyme is found suspended a-against the wall.

Therefore I’d have you not to vapour,

Nor blame the lads that use the clapper,

By which are scared the fiends of hell,

And all by virtue of a bell.

One often finds a list of rules displayed on the wall of the belfry. The following are quaintly interesting.

Whoever in this place shall swear

Sixpence he shall pay therefor.

He that rings here in his hat

Threepence he shall pay for that.

Who overturns a bell, be sure

Threepence he shall pay therefor.

Who leaves his rope under feet

Threepence he shall pay for it.

A good ringer and a true heart

Will not refuse to stand a quart.

Who will not to these rules agree

Shall not belong to this belfrie.

Drewsteignton, Devon. John Hole, Ch: Warden.

The following are the rules, orders and regulations found in the belfry at Brushford, Somerset.

Let awful silence first proclaimed be!

Next let us praise the Holy Trinity.

Then homage pay unto our valiant King,

And with a blessing raise the pleasant ring.

Hark! now the chirping treble rings it clear,

And covering Tom comes rolling in the rear.

Now up and set, let us consult and see

What laws are best to keep sobriety.

Then all consent to make this joint decree—

Let him who swears, or in an angry mood

Quarrels or strikes (although he draws no blood),

Or wears his hat, or spurs, or turns a bell,

Or by unskilful handling mars a peal,

Pay down sixpence for each crime!

(This caution shall not be effaced with time).

But if the Sexton’s these defaults should be,

From him demand a double penalty.

Whoever does his Parson disrespect,

Or Warden’s order wilfully neglect

By one and all be held in foul disgrace

And ever banished this harmonious place.

Now round let’s go with pleasure to the ear

And pierce with pleasing sounds the yielding air,

And when the bells are up, then let us sing

God save the Church, and bless Great George the King.

A.D. 1803. June 7th. Robert Gooding, Churchwarden.

The spelling in the original of the following notice is a little “mixed.”

I.H.S.

This is the belfry that is free

For all those who civil be,

And if you wish to chime or ring

There is no music played or sung

Like unto bells when they’re well rung.

Then ring your bells well if you can,

Silence is best for every man,

But if you ring in spur or hat,

Sixpence you pay be sure of that

And if a bell you overthrow

Pray pay a groat before you go.

1756, All Saints, Hastings.

THE SEVENTH SON.

Many persons believe that a seventh son can cure diseases, but that a seventh son of a seventh son, and no female child born between, can cure the King’s Evil.

SUNDAY.

In the West of England, Sunday is reckoned to be the day for leaving off any article of clothing, as then those who so divest themselves will have the prayers of every congregation in their behalf, and are sure not to catch cold.

It has also been remarked that rooks never attempt to build their nests on Sunday, even though there are but a few twigs necessary to complete them.

Some persons object to cut their nails, or turn a feather bed on Sunday.

II. Things Lucky and Unlucky

For every ill beneath the sun

There is some remedy, or none.

Should there be one, resolve to find it,

If not, submit; and never mind it.

It is difficult to define accurately the word ‘ unlucky ’ as understood by people in general. It conveys to their minds an indistinct supernatural and distressful affliction, of an awful character, and for a long time a troubled restlessness and fear of approaching evil embitters every moment of their lives, until the haunting dread wears itself out.

It however leaves behind a highly-strung nervous feeling which springs into activity at the smallest provocation.

The following examples of people’s belief in Devonshire, concerning luck, will perhaps be of interest.

IT IS LUCKY

To stumble on ascending stairs, steps or ladders: it indicates speedy marriage.

To find a cast horse-shoe.

To see the new moon over the right shoulder if one is out of doors.

To see a pin and pick it up will bring the very best of luck.

It is lucky:

To break a. piece of pottery on Good Friday, because the points of every sherd are supposed to pierce the body of Judas Iscariot.

To wean a child on Good Friday.

To carry crooked coins in the pocket.

To receive the right hand of the bishop on one’s head at confirmation.

To sow all kinds of garden seeds on Good Friday. Beans and peas sown on this day yield better crops.

To plant all kinds of ornamental shrubs on Good Friday.

To see a company of fairies dancing in the adit of a mine, as it indicates the presence of valuable lodes.

To pay money on the first of January, as it insures the blessing of ready cash for all payments throughout the year.

To spit over the right shoulder when one meets a grey horse.

To meet a flock of sheep on the highway when on a journey.

To throw a pinch of salt into the mash when brewing, to keep the witches out.

To rest bars of iron on vessels containing beer in summer. They prevent “souring of the liquor” in thundery weather.

To have crickets in the house.

It is lucky:

To see a star on the wick of a candle.

“There’s a star in the candle to-night,

One bright little spot shining clear,

To make our heavy hearts light,

By shewing that a letter is near.”

To carry a badger’s tooth in the waistcoat pocket: it brings luck at cards.

To have white specks on one’s finger nails shews that happiness is in store.

These specks are sometimes called “gifts.”

“A gift on the thumb is sure to come,

A gift on the finger is sure to linger.”

Or they may be thus enumerated:

“A gift, a friend, a foe,

A lover to come, a journey to go.”

To be born on a Sunday; because you can see spirits, and tame the dragon who watches over hidden treasure.

To bite a baby’s nails before it is a year old instead of cutting them, as it ensures its honesty through life.

To put the left stocking on first.

To put the right foot first, because it ensures success.

To fell trees at the wane of the moon, and when the wind is in the North.

It is lucky:

To be the seventh son of a seventh son, for he can, by passing his hand over the glands of the neck of a person suffering from King’s Evil, cure the disease.

On first hearing the cuckoo in spring one should run in a circle three times with the sun, to ensure good luck for the rest of the year.

If one hears the cuckoo to the right it portends good fortune, but to hear his voice on the left is a sure sign of impending misfortune.

On hearing the cuckoo’s note in April run as fast as possible to the nearest gate, and sit on the top bar to drive away the spirit of laziness. Who neglects to do this will be weak for a year, and have no inclination to work until the ensuing spring when the harbinger of spring again returns.

To possess a rope by which a person has been hanged ensures good luck.

On opening a new business, or entering upon any new commercial enterprise, the first money taken should be turned over from hand to hand and spat upon, to insure good luck in all future dealing.

IT IS UNLUCKY

To have an empty pocket (even a crooked coin keeps the devil away).

To buy a broom in May

For it sweeps all luck away.

To pass under a lean-to ladder without first crossing the middle fingers over the front ones.

“This superstition,” says the Weekly Western News, Plymouth, “originates from an old coarse joke formerly frequent among the lower class. It took its rise from the fact that at the gallows at Tyburn the culprit had to walk up a ladder, there being no platform. The ladder was afterwards withdrawn and he was left suspended.”

To break a salt-cellar.

To spill salt at table without throwing a pinch over the left shoulder.

To help one another to salt.

To kill a robin.

To tread on a cat’s tail.

To kill crickets.

To omit to inform the bees of the death of a relative, by tapping at each hive with the key of the front door. It is necessary too, to say to each hive as one taps “Maister is dead,” or “Missus is dead,” as the case may be.

To forget to put the bees in mourning, by placing a scrap of black crape or cloth on the top of each hive.

To neglect to communicate any great social or political event to the bees.

(The bees resent the omission of these ceremonies, and in consequence cease work, dwindle and die).

To give a friend a knife; as it cuts all love away.

To sneeze before breakfast.

To turn a feather-bed on Sunday.

To cut one’s nails on Sunday.

To speak while the clock is striking.

To put a pair of boots on a table.

To put bellows on a table.

To stir the leaves in the teapot before pouring out the tea.

To have a kitten and a baby in a house together. The kitten should be sent away in order to secure good health to the baby.

To cross knives.

To kill a swallow.

To pass another person on a staircase.

To break a looking-glass, for it brings seven years of trouble, or the loss of one’s best friend.

To kill a small red spider, because this insect is supposed to bring money in its track, hence it is often called the “ money-spider.”

To begin new undertakings on a Friday.

To wash clothes on Good Friday. This must be studiously avoided to prevent any member of the family dying before the year is out.

To return, or to look back when leaving the house to start on a journey, or even when going for a short walk. If compelled to return one should sit down and rest for a few minutes before making a fresh start.

To eat any kind of fish from the head downwards, as it is against the grain.

To whistle while underground, because it will awaken the evil spirits which inhabit the caves of the earth.

To be born with a blue vein across the nose.

To decorate a house with peacock’s feathers.

For a miner to meet a snail when entering a mine, as it betokens calamity, or probably the exhaustion of the lode on which he is then at work.

To see one magpie in a field, or flying across the road. Four magpies seen at one time presage death.

To reveal a child’s Christian name before it is presented at the font for baptism.

To receive the left hand of the bishop on the head, at confirmation. It conveys a ban instead of a blessing.

To burn bones, as it will bring pains and aches to the person who does so.

To put an umbrella on a table.

For a cock to crow at midnight, or a dog to howl between sun-set and sun-rise.

To change houses, or enter into service, on Friday.

To see a new moon through a glass window, or door, or over the left shoulder.

The advent of a comet is supposed to forebode disaster and national calamity.

An eclipse of the sun shews God’s displeasure.

An eclipse of the moon, that the Devil was abroad working mischief.

To see a pin and let it lie, you’ll need that and hundreds more before you die.

For a child to refrain from crying when presented at the font for baptism. It is thought the more it yells and screams, the quicker the evil spirits will quit it.

For an unmarried person to be sponsor at a baptism: for “First to the font, never to the altar.” To see a coffin-ring in a candle: it shews that some member of the household, or a very near relation, will very shortly die.

For a bird to flutter against the window-panes.

For a robin to fly into a room and utter its weep! weep! weep!

For a bride to take a last peep at the mirror before starting for church.

To look back after starting on a journey. (Remember Lot’s wife.)

To cut a baby’s nails or hair before the child is a year old.

To look into a mirror at dusk, or night-time, unless the room is well lighted is not pleasant: for there is a dread of something uncanny peeping over the shoulder; such an apparition would portend death.

To bring into a poultry-farmer’s house a small bunch of primroses when these flowers first come into bloom in the early spring. The number of chicken reared that season, are supposed to agree with the number of primroses brought in. (I once saw a little girl severely punished for this offence in South Devon.)

To hear the melancholy ticking of the “Deathwatch,” in woodwork, is an omen of death.

“Because like a watch it always cries click,

Then woe be to those in the house that be sick.” To see a raven hovering over a house is ominous of evil.

To take eggs from robins’ or wrens’ nests. Should this be done, cows feeding in the neighbourhood will yield discoloured milk, for

Robin Redbreast and Jenny Wren

Are God Almighty’s cock and hen.

To transplant parsley.

To sit down at table as one of thirteen.

To put the left foot first in starting to walk, as it indicates too much caution and brings disappointment.

For rooks to desert their rookery without any apparent reason. This forebodes ill-luck to the owners of the property. The heir will be kidnapped, or lost, and until the rooks return to their quarters, will not be brought back.

If thou be hurt with the horn of hart,

It brings thee to thy bier,

But tusk of boar will leeches heal,

Thereof have lesser fear.

Who kills a spider, Bad luck betides her.

To lose a mop or a broom at sea. Children bring good luck to a ship.

To whistle on board ship, as it raises storms, and enrages the devil, who in retaliation brews tempestuous weather and causes shipwrecks.

Save a sailor from the sea,

And he’ll become your enemy.

It is said if one’s nose itches, that one will be kissed, cursed, vexed, or shake hands with a fool. To elude the three former ills one generally invites the nearest person at hand to give a friendly grip. This appears to be rather rough on the friend.

Fishermen are exceptionally superstitious and believe that ill-luck attends certain practices: for instance, they would never think of turning a craft against the sun, or of mentioning rabbits, hares, or pigs, while aboard, nor will they lend anything from one boat to another.

It is unlucky:

If the first herring brought aboard for the season is found to be a “ melt,” then a disastrous time in the fishing world is to be expected. If on the other hand the first brought in is a roe,” then hundreds of mease (600) will be caught and full purses the result.

Fishermen consider it most unlucky to throw a cat overboard, or to drown one at sea.

Whoso the wren robs of its nest,

Health loses in a day;

The spoiler of the swallow’s house,

Will ail and pine for aye.

And he who with his ruthless hands

Shall tear the robin’s cot,

In his coffin shall have a guilty mark—

A deep red gory spot.

When unfortunate at cards you should rise from your chair, twist it round on one of its legs four times. This action is supposed to change the luck for the better.

If one’s right ear gets very hot it shows that one’s friends are speaking in laudatory terms of one.

On the other hand, if one’s left ear burns, then the friends are “ picking holes in one’s jacket.”

Let left or right burn at night, then all things are well, both in and out of sight.

UNLUCKY DAYS.

Certain days in each month are supposed to be un fortunate, upon which no new enterprise should be undertaken. If one makes a bargain, plants or sows in the garden, or begins a journey on either of these days, misfortune will quickly follow.

Days of evil strife and hate; Cruel wrath and fell debate, Planets strike and stars annoy, Aspects, aught of good destroy, Shun their calends, Heed their power.

Nought begun in evil hour E’er went well. Spirits o’er Those days preside, Who sport and gibe, With human fate;

Omens of hate, Wrath and debate.

EVIL DAYS.

January, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 9th, nth.

February, 13th, 17th, 19th.

March, 13th 15th, 16th.

April, 5th, 14th.

May, 8th, 14th.

June, 6th.

July, 16th, 19th.

August, 8th, 16th.

September, 1st, 15th, 16th

October, 16th.

November, 15th, 16th.

December, 6th, 7th, nth.

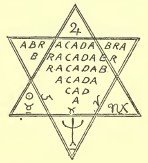

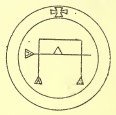

III. Charms

Where is the Necromancer? let him bring

His treasury of charms, rich syrups, herbs

Gathered in eclipse: or when shooting stars

Sow earth with pearls; or, let him call his sprites

Till the air thickens, and the golden noon

Smote by his wings, is turned to sudden midnight.

—Croly.

West Country people generally, and Devonians in particular, are exceedingly superstitious, in spite of all that has been done for them in the way of higher education, and the enlightening influence of the press. Dwellers in the hilly parts of Devon, on Dartmoor and Exmoor, and in the villages bordering upon them, are as deeply imbued with faith in witches, as their forefathers were in the days when Alfred was king.

According to tradition there are three kinds of witches.

The Black Witch, who is of an intensely malignant nature, and responsible for all the ills that flesh is heir to.

The White Witch, of an opposite nature, is always willing, for certain pecuniary considerations, to dispense charms and philtres, to cancel the evil of the other.

The Grey Witch is the worst of all, for she possesses the double power of either “overlooking” or “releasing.” -

In cases of sickness, distress, or adversity, persons at the present time (a.d. 1898) make long expensive journeys to consult the white witch, and to gain relief by her (or his) aid.

The surest method of escaping the influence of the evil eye, is to draw blood from the person of the witch. Shakespeare, in Henry UI, says:

Devil or devil’s dam, I’ll conjure thee:

Blood will I draw. Thou art a witch.

A country man told me recently that he had “raped old mother Tapp’s arm with a great rusty nail two or three times,” till he made the blood flow freely. “She can’t hurt me again arter that,” said he.

The mode of applying charms and medicaments has been handed down to us from the remotest ages. The witch doctor cured through the imagination. “ Conceit will kill and conceit will cure,” said a celebrated Harley Street physician to a medical student who one day applied to him for advice. It certainly is the case with regard to talismans. Playing on a patient’s will and feelings, has stronger power in curing disease than we are inclined to credit. To the powerful influence of strong-minded, unscrupulous persons over those of weaker constitution may be attributed the success of the nostrums prescribed. Added to the physical presence of the charm, the hypnotic persuasion of the operator compels the patient to believe that a cure has been effected through the charm.

Pinches of powdered plants, scraps of inscribed vellum, dried limbs of loathsome reptiles, juices of poisonous herbs, blood, excrements, and gruesome compositions all blend together to make up the witch’s charms. Who among the weak in mind, the uneducated, and the frivolous could resist falling a victim to the seductive attraction of a talisman, whose virtues would secure health, wealth and happiness? Much of a witch’s success depended on the unremitting persuasive force she exerted on her patients to stimulate them to believe implicitly in her. This once attained, her influence became unlimited. The degree of strength exerted affected the progress of convalescence. For mercenary reasons the witch took care that a cure was not too quickly brought about.

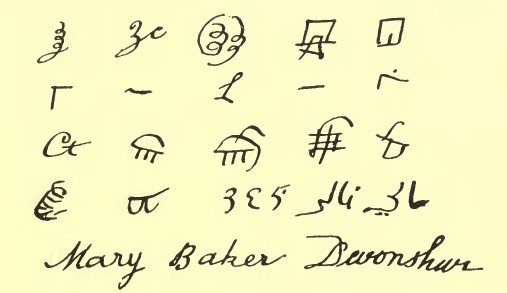

I have interviewed many a believer in the efficacy of charms, and from them obtained curious examples of miscellaneous articles claiming miraculous powers to heal. Besides the sale of charms the white witch cures diseases by “ striking ” and blessing. The following are a few examples.

TO SECURE LUCK AT GAMES OF CHANCE.

Suspend by a silken cord around the neck, a section of the rope with which a person has been hanged.

TO CURE SKIN DISEASE.

Place the poison found in a toad’s head in a leathern bag one inch square: enclose this in a white silk bag, tie it round the neck, allowing the bag to lie on the pit of the stomach. On the third day the patient will be sick. Remove and bury the bag. As it rots so will the patient get well.

TO CHARM AWAY HOUSE FLIES.

Gather and dry as much of the herb Fleabane as you can find. Each morning during the months of June, July and August, burn a handful of the herb in the rooms. The smoke will drive the flies from the house.

TO REMOVE WARTS.

Take an eel and cut off the head.

Rub the warts with the blood of the head.

Then bury the head in the ground.

When the head is rotten the warts fall off.

TO HEAL BURNS.

The witch repeats the following prayer while passing her hand three times over the burn:

Three wise men came from the east,

One brought fire, two carried frost.

Out fire! In frost!

In the Name of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.

TO BRING CREAM TO BUTTER.

Come, butter, come,

Come, butter, come,

Peter’s waiting at the gate,

Waiting for a buttered cake.

Come, butter, come.

CHARMS FOR TOOTHACHE.

(1)—Carry a dead person’s tooth in the left waistcoat pocket.

(2)—Bite a tooth from the jaw of a disinterred skull.

(3)—“As Peter sat weeping on a stone our Saviour passed by and said, ‘ Peter, why weepest thou? ’ Peter said unto Him, ‘ I have got the toothache.’ Our Saviour replied, ‘ Arise and be sound.’ ”

And whosoever keeps this in memory or in writing will never suffer from toothache.

(4)—Mix

Two quarts of rat’s broth.

One ounce of camphor.

One ounce essence of cloves.

Dose—Take one teaspoonful three times a day.

TO CURE THE COLIC.

Mix equal quantities of elixir of toads and powdered Turkey rhubarb.

Dose—Half a teaspoonful fasting for three successive mornings.

TO CHARM A BRUISE.

Holy chicha! Holy chicha!

This bruise will get well by-and-bye.

Up sun high! Down moon low!

This bruise will be quite well very soon!

In the Name of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. Amen.

TO STAUNCH BLOOD.

As Christ was born in Bethlehem and baptized in the river Jordan, He said to the water, “Be still.’’ So shall thy blood cease to flow. In the name of the Father, Son and Holy Ghost.—Amen.

TO FRUSTRATE THE POWER OF THE BLACK WITCH.

Take a cast horse shoe, nail it over the front door, points upwards. While nailing it up chant in monotone the following:

So as the fire do melt the wax

And wind blows smoke away,

So in the presence of the Lord

The wicked shall decay,

The wicked shall decay.—

Amen.

TO INSURE GOOD SIGHT.

Fennel, rose, vervain, celandine and rue,

Do water make which will the sight renew.

TO KNOW IF ONE’S PRESENT FIANCÉ WILL BE TRUE.

Procure from a butcher a bladebone of a shoulder of lamb divested of all the meat. Borrow a penknife from an unmarried man, but do not say for what purpose it is required. Take a yard of white ribbon, and having tied it to the bone, hang it as high in your bedroom chimney as you can conveniently reach. On going to bed pierce the bone with the knife once, for nine successive nights, in a different place each night, repeat while doing so, the following:

Tiz not this bone I means to stick,

But my lover’s heart I means to prick,

Wishing him neither rest nor sleep,

Till unto me he comes to speak.

At the end of nine days your sweetheart will ask you to bind a wounded finger, or to attend to a cut which he will have met with during the time the charm was being used.

TO CAUSE A FUTURE SPOUSE TO APPEAR.

Whoso wishes to see the spectre of a future husband can do so by performing the following rite. Retire to bed just before midnight, as quietly as possible. Remove the left garter, and tie it round the right stocking, while doing so repeat the following:

This knot I knit, to know the thing I know not yet

That I may see, the man that shall my husband be,

How he goes, and what he wears,

And what he does all days and years.

During the night, the future “he” will appear dressed in his ordinary attire, carrying some badge of his trade or profession.

TO DISCOVER THE INITIALS OF YOUR FUTURE HUSBAND.

On October 28th, the day dedicated to Saints Simeon and Jude, is the most propitious on which to use the following incantation for the discovery of the future one’s initials. Take a fine round apple, peel it in one whole length. Take the paring in the right hand, stand in the centre of a large room, and while waving the paring gently round your head repeat:

St. Simeon and St. Jude on you I intrude,

By this paring I hold to discover.

Without delay, tell me I pray,

The first letters of my own true lover.

Then drop the paring over the left shoulder and it will form the initial of your future husband’s name; if it break up into small pieces you will die an old maid.

TO SEE ONE’S FUTURE HUSBAND BY CHARMING THE MOON.

On seeing the new moon, make the sign of the cross three times in the air, and once on your forehead. Clasp both hands tightly together and hold them in a supplicating attitude, uplifted towards the moon. Then repeat:

All hail, all hail, to thee,

All hail to thee, new moon,

I pray to thee, new moon,

Before thou growest old,

To reveal unto me,

Who my true love shall be!

Before the moon is at full the suppliant will see her true love.

TO CURE ZWEEMY-HEADEDNESS.

Wash the head with plenty of old rum. The back and face with sour wine; wear flannel next the skin, and carry a packet of salt in the left-hand pocket.

CHARM FOR A THORN IN THE FLESH.

Our dear Lord Jesus Christ was pricked with thorns. His blood went back to FIeaven again, His flesh neither cankered, rankled, nor festered, neither shall thine, M. or N. In the name of the Father, Son and Holy Ghost.—Amen, Amen, Amen.

THE HALF-CROWN CHARM FOR THE CURE OF KING’S EVIL.