The Worship of the Generative Powers

by

Thomas Wright

First published in 1865.

Table of Contents

Antiquity

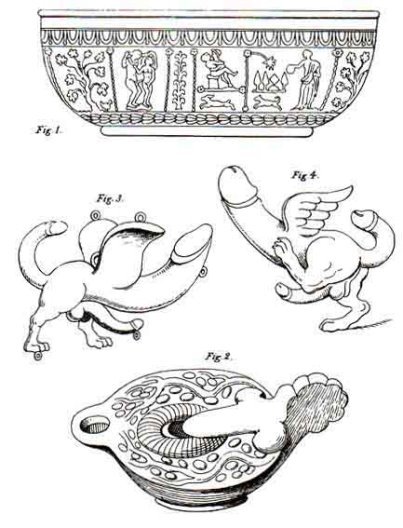

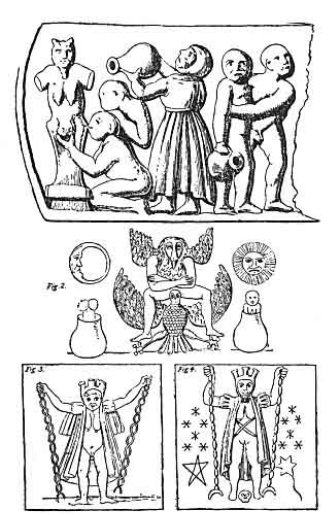

PLATE 1

RICHARD PAYNE KNIGHT has written with great learning on the origin and history of the worship of Priapus among the ancients. This worship, which was but a part of that of the generative powers, appears to have been the most ancient of the superstitions of the human race, [1] has prevailed more or less among all known peoples before the introduction of Christianity, and, singularly enough, so deeply it seems to have been implanted in human nature, that even the promulgation of the Gospel did not abolish it, for it continued to exist, accepted and often encouraged by the mediæval clergy. The occasion of Payne Knight’s work was the discovery that this worship continued to prevail in his time, in a very remarkable form, at Isernia in the kingdom of Naples, a full description of which will be found in his work. The town of Isernia was destroyed, with a great portion of its inhabitants, in the terrible earthquake which so fearfully devastated the kingdom of Naples on the 26th of July, 1805, nineteen years after the appearance of the book alluded to. Perhaps with it perished the last trace of the worship of Priapus in this particular form; but Payne Knight was not acquainted with the fact that this superstition, in a variety of forms, prevailed throughout Southern and Western Europe largely during the Middle Ages, and that in some parts it is hardly extinct at the present day; and, as its effects were felt to a more considerable extent than people in general suppose in the most intimate and important relations of society, whatever we can do to throw light upon its mediæval existence, though not an agreeable subject, cannot but form an important and valuable contribution to the better knowledge of mediæval history. Many interesting facts relating to this subject were brought together in a volume published in Paris by Monsieur J. A. Dulaure, under the title, Des Divinités Génératices chez les Anciens et les Modernes, forming part of an Histoire Abrégée des differens Cultes, by the same author. [2] This book, however, is still very imperfect; and it is the design of the following pages to give, with the most interesting of the facts already collected by Dulaure, other facts and a description and explanation of monuments, which tend to throw a greater and more general light on this curious subject.

The mediæval worship of the generative powers, represented by the generative organs, was derived from two distinct sources. In the first place, Rome invariably carried into the provinces she had conquered her own institutions and forms of worship, and established them permanently. In exploring the antiquities of these provinces, we are astonished at the abundant monuments of the worship of Priapus in all the shapes and with all the attributes and accompaniments, with which we are already so well acquainted in Rome and Italy. Among the remains of Roman civilization in Gaul, we find statues or statuettes of Priapus, altars dedicated to him, the gardens and fields entrusted to his care, and the phallus, or male member, figured in a variety of shapes as a protecting power against evil influences of various kinds. With this idea the well-known figure was sculptured on the walls of public buildings, placed in conspicuous places in the interior of the house, worn as an ornament by women, and suspended as an amulet to the necks of children. Erotic scenes of the most extravagant description covered vessels of metal, earthenware, and glass, intended, on doubt, for festivals and usages more or less connected with the worship of the principle of fecundity.

At Aix in Provence there was found, on or near the site of the ancient baths, to which it had no doubt some relation, an enormous phallus, encircled with garlands, sculptured in white marble. At Le Chatelet, in Champagne, on the site of a Roman town, a colossal phallus was also found. Similar objects in bronze, and of smaller dimensions, are so common, that explorations are seldom carried on upon a Roman site in which they are not found, and examples of such objects abound in the museums, public or private, of Roman antiquities. The phallic worship appears to have flourished especially at Nemausus, now represented by the city of Nîmes in the south of France, where the symbol of this worship appeared in sculpture on the walls of its amphitheatre and on other buildings, in forms some of which we can hardly help regarding as fanciful, or even playful. Some of the more remarkable of these are figured in our plates, II and III.

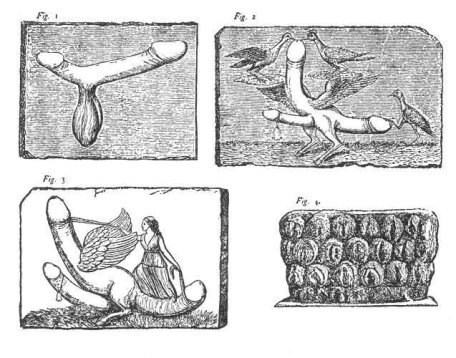

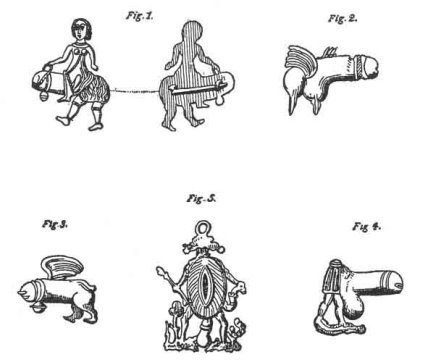

PLATE II

ROMAN SCULPTURE FROM NIMES

The first of these, Plate II, Fig 1 is the figure of a double phallus. It is sculptured on the lintel of one of the vomitories, or issues, of the second range of seats of the Roman amphitheatre, near the entrance-gate which looks to the south. The double and the triple phallus are very common among the small Roman bronzes, which appear to have served as amulets and for other similar purposes. In the latter, one phallus usually serves as the body, and is furnished with legs, generally those of the goat; a second occupies the usual place of this organ; and a third appears in that of a tail. On a pilaster of the amphitheatre of Nîmes we see a triple phallus of this description, Plate II, Fig 2 with goat’s legs and feet. A small bell is suspended to the smaller phallus in front; and the larger organ which forms the body is furnished with wings. The picture is completed by the introduction of three birds, two of which are pecking the unveiled head of the principal phallus, while the third is holding down the tail with its foot.

Several examples of these triple phalli occur in the Musée Secret of the antiquities of Herculaneum and Pompeii. In the examples figured in that work, the hind part of the main phallus assumes clearly the form of a dog; [3] and to most of them are attached small bells, the explanation of which appears as yet to be very unsatisfactory. The wings also are common attributes of the phallus in these monuments. Plutarch is quoted as an authority for the explanation of the triple phallus as intended to signify multiplication of its productive faculty. [4]

On the top of another pilaster of the amphitheatre at Nîmes, to the right of the principal western entrance, was a bas-relief, also representing a triple phallus, with legs of dog, and winged, but with a further accompaniment. (Plate II, Fig 3) A female, dressed in the Roman stola, stands upon the phallus forming the tail, and holds both it and the one forming the body with a bridle. [5] This bas-relief was taken down in 1829, and is now preserved in the museum of Nîmes.

PLATE III

MONUMENT FOUND AT NIMES IN 1825

A still more remarkable monument of this class was found in the course of excavations made at Nîmes in 1825. It is engraved in our plate XXVI, and represents a bird, apparently intended for a vulture, with spread wings and phallic tail, sitting on four eggs, each of which is designed, no doubt, to represent the female organ. The local antiquarians give to this, as to the other similar objects, an emblematical signification; but it may perhaps be more rightly regarded as a playful conception of the imagination. A similar design, with some modifications, occurs not unfrequently among Gallo-Roman antiquities. We have engraved a figure of the triple phallus governed, or guided, by the female, (Plate III, fig 3) from a small bronze plate, on which it appears in bas-relief; it is now preserved in a private collection in London, with a duplicate, which appears to have been cast from the same mould, though the plate is cut through, and they were evidently intended for suspension from the neck. Both came from the collection of M. Baudot of Dijon. The lady here bridles only the principal phallus; the legs are, as in the monument last described, those of a bird, and it is standing upon three eggs, apple-formed, and representing the organ of the other sex.

In regard to this last-mentioned object, another very remarkable monument of what appears at Nîmes to have been by no means a secret worship, was found there during some excavations on the site of the Roman baths. It is a squared mass of stone, the four sides of which, like the one represented in our engraving, are covered with similar figures of the sexual characteristics of the female, arranged in rows. (Plate II, fig 4) It has evidently served as a base, probably to a statue, or possibly to an altar. This curious monument is now preserved in the museum at Nîmes.

As Nîmes was evidently a centre of this Priapic worship in the south of Gaul, so there appear to have been, perhaps lesser, centres in other parts, and we may trace it to the northern extremities of the Roman province, even to the other side of the Rhine. On the site of Roman settlements near Xanten, in lower Hesse, a large quantity of pottery and other objects have been found, of a character to leave no doubt as to the prevalence of this worship in that quarter. [6] But the Roman settlement which occupied the site of the modern city of Antwerp appears to have been one of the most remarkable seats of the worship of Priapus in the north of Gaul, and it continued to exist there till a comparatively modern period.

When we cross over to Britain we find this worship established no less firmly and extensively in that island. Statuettes of Priapus, phallic bronzes, pottery covered with obscene pictures, are found wherever there are any extensive remains of Roman occupation, as our antiquaries know well. The numerous phallic figures in bronze, found in England, are perfectly identical in character with those which occur in France and Italy. In illustration of this fact, we give two examples of the triple phallus, which appears to have been, perhaps in accordance with the explanation given by Plutarch, an amulet in great favour. The first was found in London in 1842. (Plate I, fig 3) As in the examples found on the continent, a principal phallus forms the body, having the hinder parts of apparently a dog, with wings of a peculiar form, perhaps intended for those of a dragon. Several small rings are attached, no doubt for the purpose of suspending bells. Our second example (Plate I, fig 4) was found at York in 1844. It displays a peculiarity of action which, in this case at least, leaves no doubt that the hinder parts were intended to be those of a dog. All antiquaries of any experience know the great number of obscene subjects which are met with among the fine red pottery which is termed Samian ware, found so abundantly in all Roman sites in our island. They represent erotic scenes in every sense of the word, promiscuous intercourse between the sexes, even vices contrary to nature, with figures of Priapus, and phallic emblems. We give as an example one of the less exceptional scenes of this description, copied from a Samian bowl found in Cannon Street, London, in 1828. (Plate I, fig 1) The lamps, chiefly of earthenware, form another class of objects on which such scenes are frequently portrayed, and to which broadly phallic forms are sometimes given. One of these phallic lamps is here represented, on the same plate with the bowl of Samian ware just described. (Plate I, fig 2) It is hardly necessary to explain the subject represented by this lamp, which was found in London a few years ago.

All this obscene pottery must be regarded, no doubt, as a proof of a great amount of dissoluteness in the morals of Roman society in Britain, but it is evidence of something more. It is hardly likely that such objects could be in common use at the family table; and we are led to suppose that they were employed on special occasions, festivals, perhaps, connected with the licentious worship of which we are speaking, and such as those described in such strong terms in the satires of Juvenal. But monuments are found in this island which bear still more direct evidence to the existence of the worship of Priapus during the Roman period.

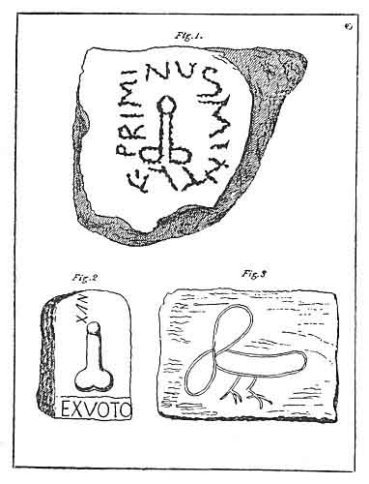

In the parish of Adel, in Yorkshire, are considerable traces of a Roman station, which appears to have been a place of some importance, and which certainly possessed temples. On the site of these were found altars, and other stones with inscriptions, which, after being long preserved in an outhouse of the rectory at Adel, are now deposited in the museum of the Philosophical Society at Leeds. One of the most curious of these, which we have here engraved for the first time, (Plate IV, fig 1) appears to be a votive offering to Priapus, who seems to be addressed under the name of Mentula. It is a rough, unsquared stone, which has been selected for possessing a tolerably flat and smooth surface; and the figure and letters were made with a rude implement, and by an unskilled workman, who was evidently unable to cut a continuous smooth line. The middle of the stone is occupied by the figure of a phallus, and round it we read very distinctly the words:--

PRIMINVS MENTLA.

The author of the inscription may have been an ignorant Latinist as well as unskilful sculptor, and perhaps mistook the ligulated letters, overlooking the limb which would make the L stand for VL, and giving A for AE. It would then read Priminus Mentalæ, Priminus to Mentula (the object personified), and it may have been a votive offering from some individual named Priminus, who was in want of an heir, or laboured under some sexual infirmity, to Priapus, whose assistance he sought. Another interpretation has been suggested, on the supposition that Mentla, or perhaps (the L being designed for IL ligulated) Mentila or Mentilla, might be the name of a female joined with her husband in this offering for their common good. The former of these interpretations seems, however, to be the most probable. This monument belongs probably to rather a late date in the Roman period. Another ex voto of the same class was found at Westerwood Fort in Scotland, one of the Roman fortresses on the wall of Antoninus. This monument [7] (Plate IV, fig 2) consisted of a square slab of stone, in the middle of which was a phallus, and under it the words EX : VOTO. Above were the letters XAN, meaning, perhaps, that the offerer had laboured ten years under the grievance of which he sought redress from Priapus. We may point also to a phallic monument of another kind, which reminds us in some degree of the finer sculptures at Nîmes. At Housesteads, in Northumberland, are seen the extensive and imposing remains of one of the Roman stations on the Wall of Hadrian named Borcovicus. The walls of the entrance gateways are especially well preserved, and on that of the guard-house attached to one of them, is a slab of stone presenting the figure given in our Plate IV, fig 3. It is a rude delineation of a phallus with the legs of a fowl, and reminds us of some of the monuments in France and Italy previously described. These phallic images were no doubt exposed in such situations because they were supposed to exercise a protective influence over the locality, or over the building, and the individual who looked upon the figure believed himself safe, during that day at least, from evil influences of various descriptions. They are found, we believe, in some other Roman stations, in a similar position to that of the phallus at Housesteads.

PLATE IV

PHALLIC MONUMENTS FOUND IN SCOTLAND

Although the worship of which we are treating prevailed so extensively among the Romans and throughout the Roman provinces, it was far from being peculiar to them, for the same superstition formed part of the religion of the Teutonic race, and was carried with that race wherever it settled. The Teutonic god, who answered to the Roman Priapus, was called, in Anglo-Saxon, Fréa, in Old Norse, Freyr, and, in Old German, Fro. Among the Swedes, the principal seat of his worship was at Upsala, and Adam of Bremen, who lived in the eleventh century, when paganism still retained its hold on the north, in describing the forms under which the gods were there represented, tells us that “the third of the gods at Upsala was Fricco [another form of the name], who bestowed on mortals peace and pleasure, and who was represented with an immense priapus;” and he adds that, at the celebration of marriages, they offered sacrifice to Fricco. This god, indeed, like the Priapus of the Romans, presided over generation and fertility, either of animal life or of the produce of the earth, and was invoked accordingly. Ihre, in his Glossarium Sueco-Gothicum, mentions objects of antiquity dug up in the north of Europe, which clearly prove the prevalence of phallic rites. To this deity, or to his female representative of the same name, the Teutonic Venus, Friga, the fifth day of the week was dedicated, and on that account received its name, in Anglo-Saxon, Frige-dæg, and in modern English, Friday. Frigedæg appears to have been a name sometimes given in Anglo-Saxon to Frea himself; in a charter of the date of 959, printed in Kemble’s Codex Diplomaticus, one of the marks on a boundary-line of land is Frigedæges-Tréow, meaning apparently Frea’s tree, which was probably a tree dedicated to that god, and the scene of Priapic rites. There is a place called Fridaythorpe in Yorkshire, and Friston, a name which occurs in several parts of England, means, probably, the stone of Frea or of Friga; and we seem justified in supposing that this and other names commencing with the syllable Fri or Fry, are so many monuments of the existence of the phallic worship among our Anglo-Saxon forefathers. Two customs cherished among our old English popular superstitions are believed to have been derived from this worship, the need-fires, and the procession of the boar’s head at the Christmas festivities. The former were fires kindled at the period of the summer solstice, and were certainly in their origin religious observances. The boar was intimately connected with the worship of Frea. [8]

From our want of a more intimate knowledge of this part of Teutonic paganism, we are unable to decide whether some of the superstitious practices of the middle ages were derived from the Romans or from the peoples who established themselves in the provinces after the overthrow of the western empire; but in Italy and in Gaul (the southern parts especially), where the Roman institutions and sentiments continued with more persistence to hold their influence, it was the phallic worship of the Romans which, gradually modified in its forms, was thus preserved, and, though the records of such a worship are naturally accidental and imperfect, yet we can distinctly trace its existence to a very late period. Thus, we have clear evidence that the phallus, in its simple form, was worshipped by the mediæval Christians, and that the forms of Christian prayer and invocation were actually addressed to it. One name of the male organ among the Romans was fascinum; it was under this name that it was suspended round the necks of women and children, and under this name especially it was supposed to possess magical influences which not only acted upon others, but defended those who were under its protection from magical or other evil influences from without. Hence are derived the words to fascinate and fascination. The word is used by Horace, and especially in the epigrams of the Priapeia, which may be considered in some degree as the exponents of the popular creed in these matters. Thus we have in one of these epigrams the lines,--

“Placet, Priape? qui sub arboris coma

Soles, sacrum revincte pampino caput,

Ruber sedere cum rebente fascino.”

Priap. Carm. lxxxiv.

It seems probable that this had become the popular, or vulgar, word for the phallus, at least taken in this point of view, at the close of the Roman power, for the first very distinct traces of its worship which we find afterwards introduce it under this name, which subsequently took in French the form fesne. The mediæval worship of the fascinum is first spoken of in the eighth century.

An ecclesiastical tract entitled Judicia Sacerdotalia de Criminibus, which is ascribed to the end of that century, directs that “if any one has performed incantation to the fascinum, or any incantation whatever, except any one who chaunts the Creed or the Lord’s Prayer, let him do penance on bread and water during three lents.”

An act of the council of Châlons, held in the ninth century, prohibits the same practice almost in the same words; and Burchardus repeats it again in the twelfth century, [9] a proof of the continued existence of this worship. That it was in full force long after this is proved by the statutes of the synod of Mans, held in 1247, which enjoin similarly the punishment for him “who has sinned to the fascinum, or has performed any incantations, except the creed, the pater noster, or other canonical prayer.”

This same provision was adopted and renewed in the statutes of the synod of Tours, held in 1396, in which, as they were published in French, the Latin fascinum is represented by the French fesne. The fascinum to which such worship was directed must have been something more than a small amulet.

Middle Ages And Renaissance

This brings us to the close of the fourteenth century, and shows us how long the outward worship of the generative powers, represented by their organs, continued to exist in Western Europe to such a point as to engage the attention of ecclesiastical synods. During the previous century facts occurred in our own island illustrating still more curiously the continuous existence of the worship of Priapus, and that under circumstances which remind us altogether of the details of the phallic worship under the Romans. It will be remembered that one great object of this worship was to obtain fertility either in animals or in the ground, for Priapus was the god of the horticulturist and the agriculturist. St. Augustine, declaiming against the open obscenities of the Roman festival of the Liberalia, informs us that an enormous phallus was carried in a magnificent chariot into the middle of the public place of the town with great ceremony, where the most respectable matron advanced and placed a garland of flowers “on this obscene figure;” and this, he says: was done to appease the god, and “to obtain an abundant harvest, and remove enchantments from the land.” [10] We learn from the Chronicle of Lanercost that, in the year 1268, a pestilence prevailed in the Scottish district of Lothian, which was very fatal to the cattle, to counteract which some of the clergy--bestiales, habitu claustrales, non animo--taught the peasantry to make a fire by the rubbing together of wood (this was the need-fire), and to raise up the image of Priapus, as a means of saving their cattle. “When a lay member of the Cistercian order at Fenton had done this before the door of the hall, and had sprinkled the cattle with a dog’s testicles dipped in holy water, and complaint had been made of this crime of idolatry against the lord of the manor, the latter pleaded in his defence that all this was done without his knowledge and in his absence, but added, ‘while until the present month of June other people’s cattle fell ill and died, mine were always found, but now every day two or three of mine die, so that I have few left for the labours of the field.’” Fourteen years after this, in 1282, an event of the same kind occurred at Inverkeithing, in the present county of Fife in Scotland. The cause of the following proceedings is not stated, but it was probably the same as that for which the cistercian of Lothian had recourse to the worship of Priapus. In the Easter week of the year just stated (March 29-April 5), a parish priest of Inverkeithing, named John, performed the rites of Priapus, by collecting the young girls of the town, and making them dance round the figure of this god; without any regard for the sex of these worshippers, he carried a wooden image of the male members of generation before them in the dance, and himself dancing with them, he accompanied their songs with movements in accordance, and urged them to licentious actions by his no less licentious language. The more modest part of those who were present felt scandalized with the priest, but he treated their words with contempt, and only gave utterance to coarser obscenities. He was cited before his bishop, defended himself upon the common usage of the country, and was allowed to retain his benefice; but he must have been rather a worldly priest, after the style of the middle ages, for a year afterwards he was killed in a vulgar brawl.

The practice of placing the figure of a phallus on the walls of buildings, derived, as we have seen, from the Romans, prevailed also in the middle ages, and the buildings especially placed under the influence of this symbol were churches.

It was believed to be a protection against enchantments of all kinds, of which the people of those times lived in constant terror, and this protection extended over the place and over those who frequented it, provided they cast a confiding look upon the image.

Such images were seen, usually upon the portals, on the cathedral church of Toulouse, on more than one church in Bourdeaux, and on various other churches in France, but, at the time of the revolution, they were often destroyed as marks only of the depravity of the clergy.

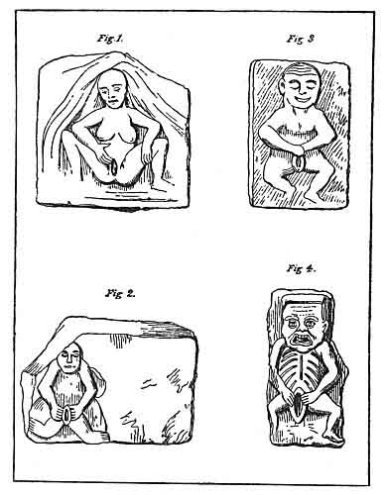

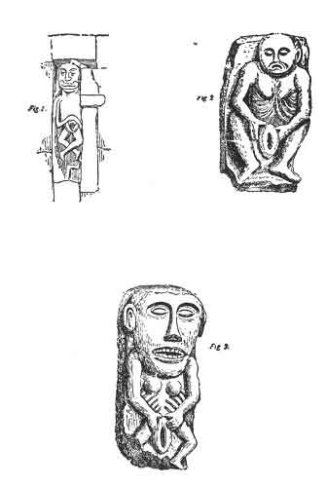

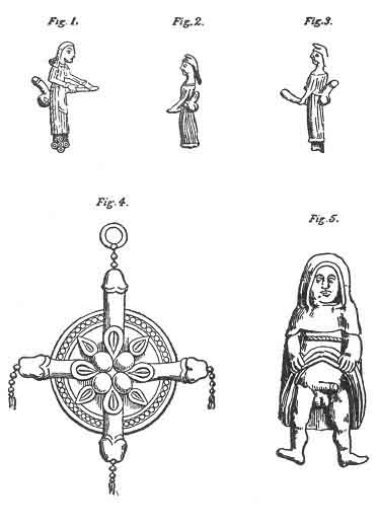

PLATE V

SHELAH-NA-GIG MONUMENTS

Dulaure tells us that an artist, whom he knew, but whose name he has not given, had made drawings of a number of these figures which he had met with in such situations. A Christian saint exercised some of the qualities thus deputed to Priapus; the image of St. Nicholas was usually painted in a conspicuous position in the church, for it was believed that whoever had looked upon it was protected against enchantments, and especially against that great object of popular terror, the evil eye, during the rest of the day.

Shelah-Na-Gigs

It is a singular fact that in Ireland it was the female organ which was shown in this position of protector upon the churches, and the elaborate though rude manner in which these figures were sculptured, show that they were considered as objects of great importance. They represented a female exposing herself to view in the most unequivocal manner, and are carved on a block which appears to have served as the key-stone to the arch of the door-way of the church, where they were presented to the gaze of all who entered. They appear to have been found principally in the very old churches, and have been mostly taken down, so that they are only found among the ruins. People have given them the name of Shelah-na-Gig, which, we are told, means in Irish Julian the Giddy, and is simply a term for an immodest woman; but it is well understood that they were intended as protecting charms against the fascination of the evil eye. We have given copies of all the examples yet known in our plates V and VI. The first of these (Plate V, fig 1) was found in an old church at Rochestown, in the county of Tipperary, where it had long been known among the people of the neighbourhood by the name given above. It was placed in the arch over the doorway, but has since been taken away. Our second example of the Shelah-na-Gig (Plate V, fig 2) was taken from an old church lately pulled down in the county Cavan, and is now preserved in the museum of the Society of Antiquaries of Dublin. The third (Plate V, fig 3) was found at Ballinahend Castle, also in the county of Tipperary; and the fourth (Plate V, fig 4) is preserved in the museum at Dublin, but we are not informed from whence it was obtained. The next, (Plate VI, fig 1) which is also now preserved in the Dublin Museum, was taken from the old church on the White Island, in Lough Erne, county Fermanagh. This church is supposed by the Irish antiquaries to be a structure of very great antiquity, for some of them would carry its date as far back as the seventh century, but this is probably an exaggeration. The one which follows (Plate VI, fig 2) was furnished by an old church pulled down by order of the ecclesiastical commissioners, and it was presented to the museum at Dublin, by the late Dean Dawson. Our last example (Plate VI, fig 3) was formerly in the possession of Sir Benjamin Chapman, Bart., of Killoa Castle, Westmeath, and is now in a private collection in London. It was found in 1859 at Chloran, in a field on Sir Benjamin’s estate known by the name of the “Old Town,” from whence stones had been removed at previous periods, though there are now very small remains of building. This stone was found at a depth of about five feet from the surface, which shows that the building, a church no doubt, must have fallen into ruin a long time ago. Contiguous to this field, and at a distance of about two hundred yards from the spot where the Shelah-na-Gig was found, there is an abandoned churchyard, separated from the Old Town field only by a loose stone wall.

The belief in the salutary power of this image appears to be a superstition of great antiquity, and to exist still among all peoples who have not reached a certain degree of civilization. The universality of this superstition leads us to think that Herodotus may have erred in the explanation he has given of certain rather remarkable monuments of a remote antiquity. He tells us that Sesostris, king of Egypt, raised columns in some of the countries he conquered, on which he caused to be figured the female organ of generation as a mark of contempt for those who had submitted easily. [11] May not these columns have been intended, if we knew the truth, as protections for the people of the district in which they stood, and placed in the position where they could most conveniently been seen? This superstitious sentiment may also offer the true explanation of an incident which is said to have been represented in the mysteries of Eleusis. Ceres, wandering over the earth in search of her daughter Proserpine, and overcome with grief for her loss, arrived at the hut of an Athenian peasant woman named Baubo, who received her hospitably, and offered her to drink the refreshing mixture which the Greeks call Cyceon (κυκεων).

PLATE VI

SHELAH-NA-GIG MONUMENTS

The goddess rejected the offered kindness, and refused all consolation. Baubo, in her distress, bethought her of another expedient to allay the grief of her guest. She relieved her sexual organs of that outward sign which is the evidence of puberty, and then presented them to the view of Ceres, who, at the sight, laughed, forgot her sorrows, and drank the cyceon. [12] The prevailing belief in the beneficial influence of this sight, rather than a mere pleasantry, seems to afford the best explanation of this story.

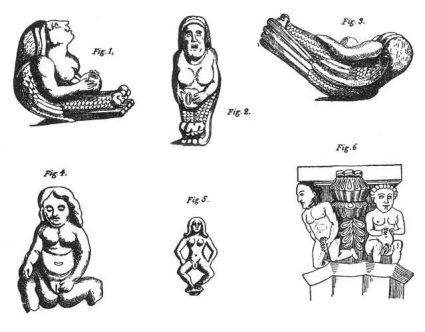

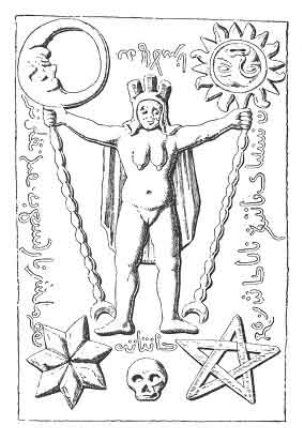

This superstition which, as shown by the Shelah-na-Gigs of the Irish churches, prevailed largely in the middle ages, explains another class of antiquities which are not uncommon. These are small figures of nude females exposing themselves in exactly the same manner as in the sculptures on the churches in Ireland just alluded to. Such figures are found not only among Roman, Greek, and Egyptian antiquities, but among every people who had any knowledge of art, from the aborigines of America to the far more civilized natives of Japan; and it would be easy to give examples from almost every country we know, but we confine ourselves to our more special part of the subject. In the last century, a number of small statuettes in metal, in a rude but very peculiar style of art, were found in the duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, in a part of Germany formerly occupied by the Vandals, and by the tribe of the Obotrites, considered as a division of the Vendes. They appeared to be intended to represent some of the deities worshipped by the people who made them; and some of them bore inscriptions, one of which was in Runic characters. From this circumstance we should presume that they belonged to a period not much, if any, older than the fall of the Western Empire. Some time afterwards, a few statuettes in metal were found in the island of Sardinia, so exactly similar to those just mentioned, that D’Hancarville, who published an account of them with engravings, considered himself justified in ascribing them to the Vandals, who occupied that island, as well as the tract of Germany alluded to. [13] One of these images, which D’Hancarville considers to be the Venus of the Vandal mythology, represents a female in a reclining position, with the wings and claws of a bird, holding to view a pomegranate, open, which, as D’Hancarville remarks, was considered as a sign representing the female sexual organ. In fact, it was a form and idea more unequivocally represented in the Roman figures which we have already described, (Plate II, fig 4, Plate VII, Plate XII,fig 3) but which continued through the middle ages, and was preserved in a popular name for that organ, abricot, or expressed more energetically, abricot fendu, used by Rabelais, and we believe still preserved in France. This curious image is represented, after D’Hancarville, in three different points of view, in our plate. (Plate VII, figs 1, 2, 3) Several figures of a similar description, but representing the subject in a more matter-of-fact shape, were brought from Egypt by a Frenchman who held an official situation in that country, and three of them are now in a private collection in London. We have engraved one of these small bronzes, (Plate VII, fig 4) which, as will be seen, presents in exact counterpart of the Shelah-na-Gig.

These Egyptian images belonged no doubt to the Roman period. Another similar figure, (Plate VII, fig 5) made of lead, and apparently mediæval, was found at Avignon, and is preserved in the same private collection just alluded to; and a third, (Plate XII, fig 4) was dug up, about ten years ago, at Kingston-on-Thames. The form of these statuettes seems to show that they were intended as portable images, for the same purpose as the Shelahs, which people might have ready at hand to look upon for protection whenever they were under fear of the influence of the evil eye, or of any other sort of enchantment.

We have not as yet any clear evidence of the existence of the Shelah-na-Gig in churches out of Ireland. We have been informed that an example has been found in one of the little churches on the coast of Devon; and there are curious sculptures, which appear to be of the same character, among the architectural ornamentation of the very early church of San Fedele at Como in Italy. Three of these are engraved in our plate VIII. On the top of the right hand jamb of the door (Plate VIII, fig 1) is a naked male figure, and in the same position on the other side a female, (Plate VIII, fig 2) which are described to us as representing Adam and Eve, and our informant, to whom we owe the drawings describes that at the apex (Plate VIII, fig 3) merely as “the figure of a woman holding her legs apart.”

PLATE VII

VENUS OF THE VANDALS, BRONZE AND LEAD IMAGES, AND CAPITAL OF A COLUMN

We understand that the surface of the stone in these sculptures is so much worn that it is quite uncertain whether the sexual parts were ever distinctly marked, but from the postures and positions of the hands, and the situation in which these figures are placed, they seem to resemble closely, except in their superior style of art, the Shelah-na-Gigs of Ireland. There can be little doubt that the superstition to which these objects belonged gave rise to much of the indecent sculpture which is so often found upon mediæval ecclesiastical buildings. The late Baron von Hammer-Pürgstall published a very learned paper upon monuments of various kinds which he considered as illustrating the secret history of the order of the Templars, from which we learn that there was in his time a series of most extraordinary obscene sculptures in the church of Schoengraber in Austria, of which he intended to give engravings, but the drawings had not arrived in time for his book; [14] but he has engraved the capital of a column in the church of Egra, a town of Bohemia, of which we give a copy (Plate VII, fig 6), [15] in which the two sexes are displaying to view the members, which were believed to be so efficatious against the power of fascination.

The figure of the female organ, as well as the male, appears to have been employed during the middle ages of Western Europe far more generally than we might suppose, placed upon buildings as a talisman against evil influences, and especially against witchcraft and the evil eye, and it was used for this purpose in many other parts of the world. It was the universal practice among the Arabs of Northern Africa to stick up over the door of the house or tent, or put up nailed on a board in some other way, the generative organ of a cow, mare, or female camel, as a talisman to avert the influence of the evil eye. It is evident that the figure of this member was far more liable to degradation in form than that of the male, because it was much less easy, in the hands of rude draughtsmen, to delineate in an intelligible form, and hence it soon assumed shapes which though intended to represent it, we might rather call symbolical of it, though no symbolism was intended. Thus the figure of the female organ easily assumed the rude form of a horseshoe, and as the original meaning was forgotten, would be readily taken for that object, and a real horseshoe nailed up for the same purpose. In this way originated, apparently, from the popular worship of the generative powers, the vulgar practice of nailing a horseshoe upon buildings to protect them and all they contain against the power of witchcraft, a practice which continues to exist among the peasantry in some parts of England at the present day. Other marks are found, sometimes among the architectural ornaments, such as certain triangles and triple loops, which are perhaps typical forms of the same object. We have been informed that there is an old church in Ireland where the male organ is drawn on one side of the door, and the Shelah-na-Gig on the other, and that, though perhaps comparatively modern, their import as protective charms are well understood. We can easily imagine men, under the influence of these superstitions, when they were obliged to halt for a moment by the side of a building, drawing upon it such a figure, with the design that it should be a protection to themselves, and thus probably we derive from superstitious feelings the common propensity to draw phallic figures on the sides of vacant walls and in other places.

Priapus Worship

Antiquity had made Priapus a god, the middle ages raised him into a saint, and that under several names. In the south of France, Provence, Languedoc, and the Lyonnais, he was worshipped under the title of St. Foutin. [16] This name is said to be a mere corruption of Fotinus or Photinus, the first bishop of Lyons, to whom, perhaps through giving a vulgar interpretation to the name, people had transferred the distinguishing attribute of Priapus. This was a large phallus of wood, which was an object of reverence to the women, especially to those who were barren, who scraped the wooden member, and, having steeped the scrapings in water, they drank the latter as a remedy against their barrenness, or administered it to their husbands in the belief that it would make them vigorous. The worship of this saint, as it was practiced in various places in France at the commencement of the seventeenth century, is described in that singular book, the Confession de Sancy. [17] We there learn that at Varailles in Provence, waxen images of the members of both sexes were offered to St. Foutin, and suspended to the ceiling of his chapel, and the writer remarks that, as the ceiling was covered with them, when the wind blew them about, it produced an effect which was calculated to disturb very much the devotions of the worshippers. We hardly need remark that this is just the same kind of worship which existed at Isernia, in the kingdom of Naples, where it was presented in the same shape. At Embrun, in the department of the Upper Alps, the phallus of St. Foutin was worshipped in a different form; the women poured a libation of wine upon the head of the phallus, which was collected in a vessel, in which it was left till it became sour; it was then called the “sainte vinaigre,” and the women employed it for a purpose which is only obscurely hinted at. When the Protestants took Embrun in 1585, they found this phallus laid up carefully among the relics in the principal church, its head red with the wine which had been poured upon it. A much larger phallus of wood, covered with leather, was an object of worship in the church of St. Eutropius at Orange, but it was seized by the Protestants and burnt publicly in 1562. St. Foutin was similarly an object of worship at Porigny, at Cives in the diocese of Viviers, at Vendre in the Bourbonnais, at Auxerre, at Puy-en-Velay, in the convent of Girouet near Sampigny, and in other places. At a distance of about four leagues from Clermont in Auvergne, there is (or was) an isolated rock, which presents the form of an immense phallus, and which is popularly called St. Foutin. Similar phallic saints were worshipped under the names of St. Guerlichon, or Greluchon, at Bourg-Dieu in the diocese of Bourges, of St. Gilles in the Cotentin in Britany, of St. Rene in Anjou, of St. Regnaud in Burgundy, of St. Arnaud, and above all of St. Guignolé near Brest and at the village of La Chatelette in Berri. Many of these were still in existence and their worship in full practice in the last century; in some of them, the wooden phallus is described as being much worn down by the continual process of scraping, while in others the loss sustained by scraping was always restored by a miracle. This miracle, however, was a very clumsy one, for the phallus consisted of a long staff of wood passed through a hole in the middle of the body, and as the phallic end in front became shortened, a blow of a mallet from behind thrust it forward, so that it was restored to its original length.

It appears that it was also the practice to worship these saints in another manner, which also was derived from the forms of the worship of Priapus among the ancients, with whom it was the custom, in the nuptial ceremonies, for the bride to offer up her virginity to Priapus, and this was done by placing her sexual parts against the end of the phallus, and sometimes introducing the latter, and even completing the sacrifice. This ceremony is represented in a bas-relief in marble, an engraving of which is given in the Musée Secret of the antiquities of Herculaneum and Pompeii; its object was to conciliate the favour of the god, and to avert sterility. It is described by the early Christian writers, such as Lactantius and Arnobius, as a very common practice among the Romans; and it still prevails to a great extent over most part of the East, from India to Japan and the islands of the Pacific. In a public square in Batavia, there is a cannon taken from the natives and placed there as a trophy by the Dutch government. It presents the peculiarity that the touch-hole is made on a phallic hand, the thumb placed in the position which is called the “fig,” and which we shall have to describe a little further on. It is always the same idea of reverence to the fertilizing powers of nature, of which the garland or the bunch of flowers was an appropriate emblem. There are traces of the existence of this practice in the middle ages. In the case of some of the priapic saints mentioned above, women sought a remedy for barrenness by kissing the end of the phallus; sometimes they appear to have placed a part of their body naked against the image of the saint, or to have sat upon it. This latter trait was perhaps too bold an adoption of the indecencies of pagan worship to last long, or to be practiced openly; but it appears to have been more innocently represented by lying upon the body of the saint, or sitting upon a stone, understood to represent him without the presence of the energetic member. In a corner in the church of the village of St. Fiacre, near Mouceaux in France, there is a stone called the chair of St. Fiacre, which confers fecundity upon women who sit upon it; but it is necessary that nothing should intervene between their bare skin and the stone. In the church of Orcival in Auvergne, there was a pillar which barren women kissed for the same purpose, and which had perhaps replaced some less equivocal object. [18] Traditions, at least, of similar practices were connected with St. Foutin, for it appears to have been the custom for girls on the point of marriage to offer their last maiden robe to that saint. This superstition prevailed to such an extent that it became proverbial. A story is told of a young bride who, on the wedding night, sought to deceive her husband on the question of her previous chastity, although, as the writer expresses it, “she had long ago deposited the robe of her virginity on the altar of St. Foutin.” From this form of superstition is said to have arisen a vice which is understood to prevail especially in nunneries--the use by women of artificial phalli, which appears in its origin to have been a religious ceremony. It certainly existed at a very remote period, for it is distinctly alluded to in the Scriptures, [19] where it is evidently considered as a part of pagan worship. It is found at an early period of the middle ages, described in the Ecclesiastical Penitentials, with its appropriate amount of penitence. One of these penitential canons of the eighth century speaks of “a woman who, by herself or with the help of another woman, commits uncleanness,” for which she was to do penance for three years, one on bread and water; and if this uncleanness was committed with a nun, the penance was increased to seven years, two only on bread and water. Another Penitential of an early date provides for the case in which both the women who participated in this act should be nuns; and Burchardus, bishop of Worms, one of the most celebrated authorities on such subjects, describes the instrument and use of it in greater detail. The practice had evidently lost its religious character and degenerated into a mere indulgence of the passions.

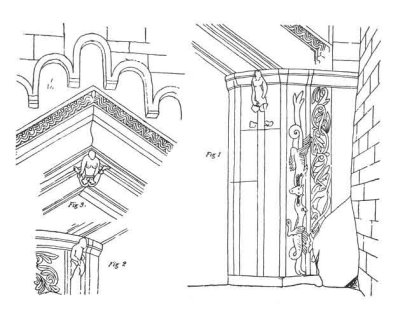

PLATE VIII

CAPITAL OF A COLUMN

Antwerp has been described as the Lampsacus of Belgium, and Priapus was, down to a comparatively modern period, its patron saint, under the name of Ters, a word the deriviation of which appears to be unknown, but which was identical in meaning with the Greek phallus and the Latin fascinum. John Goropius Becan, who published a learned treatise on the antiquities of Antwerp in the middle of the sixteenth century, informs us how much this Ters was reverenced in his time by the Antwerpians, especially by the women, who invoked it on every occasion when they were taken by surprise or sudden fear. [20] He states that “if they let fall by accident a vessel of earthenware, or stumbled, or if any unexpected accident caused them vexation, even the most respectable women called aloud for the protection of Priapus under this obscene name.” Goropius Becanus adds that there was in his time, over the door of a house adjoining the prison, a statue which had been furnished with a large phallus, then worn away or broken off. Among other writers who mention this statue is Abraham Golnitz, who published an account of his travels in France and Belgium, in 1631 [21] and he informs us that it was a carving in stone, about a foot high, with its arms raised up, and its legs spread out, and that the phallus had been entirely worn out by the women, who had been in the habit of scraping it and making a potion of the dust which they drank as a preservative against barrenness. Golnitz further tells us that a figure of Priapus was placed over the entrance gate to the enclosure of the temple of St. Walburgis at Antwerp, which some antiquaries imagined to have been built on the site of a temple dedicated to that deity. It appears from these writers that, at certain times, the women of Antwerp decorated the phalli of these figures with garlands.

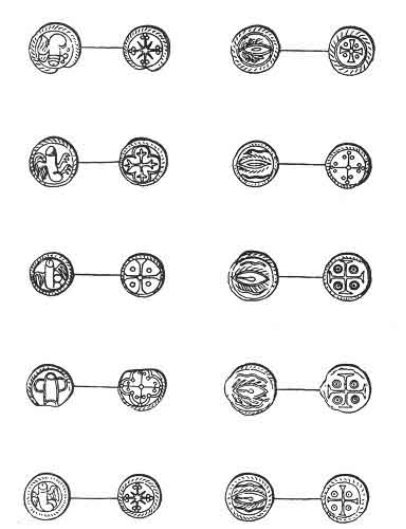

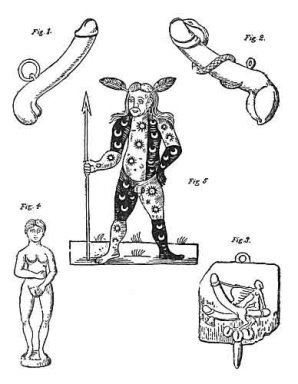

Phallic Amulets

The use of priapic figures as amulets, to be carried on the person as preservatives against the evil eye and other noxious influences, which we have spoken of as so common among the Romans, was certainly continued through the middle ages, and, as we shall see presently, has not entirely disappeared. It was natural enough to believe that if this figure were salutary when merely looked upon, it must be much more so when carried constantly on the person. The Romans gave the name fascinum, in old French fesne, to the phallic amulet, as well as to the same figure under other circumstances. It is an object of which we could hardly expect to find direct mention in mediæval writers, but we meet with examples of the object itself, usually made of lead (a proof of its popular character), and ranging in date perhaps from the fourteenth to the earlier part of the sixteenth century. As we owe our knowledge of these phallic amulets almost entirely to one collector, M. Forgeais of Paris, who obtained them chiefly from one source--the river Seine, our present acquaintance with them may be considered as very limited, and we have every reason for believing that they had been in use during the earlier period. We can only illustrate this part of the subject by describing a few of these mediæval phallic amulets, which are preserved in some private collections; and we will first call attention to a series of objects, the real purpose of which appears to be very obscure. They are small leaden tokens or medalets, bearing on the obverse the figure of the male or female organ, and on the reverse a cross, a curious intimation of the adoption of the worship of the generative powers among Christians. These leaden tokens, found in the river Seine, were first collected and made known to antiquaries by M. Forgeais, who published examples of them in his work on the leaden figures found in that river. [22] We give five examples of the medals of each sex, obverse and reverse. (Plate IX) It will be seen that the phalli on these tokens are nearly all furnished with wings; one has a bird’s legs and claws; and on another there is an evident intention to represent a bell suspended to the neck. These characteristics show either a very distinct tradition of the forms of the Roman phallic ornament, or an imitation of examples of Roman phalli then existing--possibly the latter. But this is not necessary, for the bells borne by two examples, given in our next plate, and also taken from the collection of M. Forgeais are mediæval, and not Roman bells, though these also represent well-known ancient forms of treating the subject. In the first, (Plate X, fig 1) a female is riding upon the phallus, which has men’s legs, and is held by a bridle.

PLATE IX

ORNAMENTS FROM THE CHURCH OF SAN FEDELE

This figure was evidently intended to be attached to the dress as a brooch, for the pin which fixed it still remains on the back. Two other examples (Plate X, figs 2, 3) present figures of winged phalli, one with a bell, and the other with the ring remaining from which the bell has no doubt been broken. One of these has the dog’s legs. A fourth example (Plate X, fig 4) represents an enormous phallus attached to the middle of a small man. In another, (Plate X, fig 5) which was evidently intended for suspension, probably at the neck, the organs of the two sexes are joined together.

Three other leaden figures, (Plate XI, figs 1, 2, 3) apparently amulets, which were in the Forgeais collection, offer a very peculiar variety of form, representing a figure, which we might suppose to be a male by its attributes, though it has a very feminine look, and wears the robe and hood of a woman. Its peculiarity consists in having a phallus before and behind. We have on the same plate (Plate XI, fig 4) a still more remarkable example of the combination of the cross with the emblems of the worship of which we are treating, in an object found at San Agati di Goti, near Naples, which was formerly in the Beresford Fletcher collection, and is now in that of Ambrose Ruschenberger, Esq., of Boston, U. S. It is a crux ansata, formed by four phalli, with a circle of female organs round the centre; and appears by the loop to have been intended for suspension. As this cross is of gold, it had no doubt been made for some personage of rank, possibly an ecclesiastic; and we can hardly help suspecting that it had some connection with priapic ceremonies or festivities. The last figure on the same plate is also taken from the collection of M. Forgeais. (Plate XI, fig 5) From the monkish cowl and the cord round the body, we may perhaps take it for a satire upon the friars, some of whom wore no breeches, and they were all charged with being great corruptors of female morals.

In Italy we can trace the continuous use of these phallic amulets down to the present time much more distinctly than in our more Western countries.

There they are still in very common use, and we give two examples (Plate XII, figs 1, 2) of bronze amulets of this description, which are commonly sold in Naples at the present day for a carlo, equivalent to fourpence in English money, each. One of them, it will be seen, is encircled by a serpent. So important are these amulets considered for the personal safety of those who possess them, that there is hardly a peasant who is without one, which he usually carries in his waistcoat pocket.

The ‘Fig’

There was another, and less openly apparent, form of the phallus, which has lasted as an amulet during almost innumerable ages. The ancients had two forms of what antiquaries have named the phallic hand, one in which the middle finger was extended at length, and the thumb and other fingers doubled up, while in the other the whole hand was closed, but the thumb was passed between the first and middle fingers. The first of these forms appears to have been the more ancient, and is understood to have been intended to represent, by the extended middle finger, the membrum virile, and by the bent fingers on each side the testicles. Hence the middle finger of the hand was called by the Romans, digitus impudicus, or infamis. It was called by the Greeks καταπύγων, which had somewhat the same meaning as the Latin word, except that it had reference especially to degrading practices, which were then less concealed than in modern times. To show the hand in this form was expressed in Greek by the word πκιμαλίζειν, and was considered as a most contemptuous insult, because it was understood to intimate that the person to whom it was addressed was addicted to unnatural vice. This was the meaning also given to it by the Romans, as we learn from the first lines of an epigram of Martial:--

“Rideto, multum, qui te, Sextille, cinædum

Dixerit, et digitum porrigito medium.”

Martial, Ep. ii, 28.

Nevertheless, this gesture of the hand was looked upon at an early period as an amulet against magical influences, and, formed of different materials, it was carried on the person in the same manner as the phallus. It is not an uncommon object among Roman antiquities, and was adopted by the Gnostics as one of their symbolical images. The second of these forms of the phallic hand, the intention of which is easily seen (the thumb forming the phallus), was also well known among the Romans, and is found made of various material, such as bronze, coral, lapis lazuli, and chrystal, of a size which was evidently intended to be suspended to the neck or to some other part of the person. In the Musée Secret at Naples, there are examples of such amulets, in the shape of two arms joined at the elbow, one terminating in the head of a phallus, the other having a hand arranged in the form just described, which seem to have been intended for pendents to ladies’ ears. This gesture of the hand appears to have been called at a later period of Latin, though we have no knowledge of the date at which this use of the word began, ficus, a fig. Ficusbeing a word in the feminine gender, appears to have fallen in the popular language into the more common form of feminine nouns, fica, out of which arose the Italian fica (now replaced by fico), the Spanish higa, and the French figue. Florio, who gives the word fica, a fig, says that it was also used in the sense of “a woman’s quaint,” so that it may perhaps be classed with one or two other fruits, such as the pomegranate and the apricot, to which a similar erotic meaning was given. [23] The form, under this name, was preserved through the middle ages, especially in the South of Europe, where Roman traditions were strongest, both as an amulet and as an insulting gesture.

PLATE X

PHALLIC LEADEN TOKENS FROM THE SEINE

The Italian called this gesture fare la fica, to make or do the fig to any one; the Spaniard, dar una higa, to give a fig; and the Frenchman, like the Italian, faire la figue. We can trace this phrase back to the thirteenth century at least. In the judicial proceedings against the Templars in Paris in 1309, one of the brethren of the Order was asked, jokingly, in his examination, because he was rather loose and flippant in his replies, “if he had been ordered by the said receptor (the officer of the Templars who admitted the new candidate) to make with his fingers the fig at the crucifix.” Here the word used is the correct Latin ficus; and it is the same in the plural, in a document of the year 1449, in which an individual is said to have made figs with both hands at another. This phrase appears to have been introduced into the English language in the time of Elizabeth and to have been taken from the Spaniards, with whom our relations were then intimate. This we assume from the circumstance that the English phrase was “to give the fig” (dar la higa), [24] and that the writers of the Elizabethan age call it “the fig of Spain.” Thus, ancient “Pistol, in Shakespeare:--

---- “A figo for thy friendship!--

The fig of Spain.” Henry V, III. 6.

The phrase has been preserved in all these countries down to modern times and we still say in English, “a fig for anybody,” or “for anything,” not meaning that we estimate them at no more than the value of a fig, but that we throw at them that contempt which was intimated by showing them the phallic hand, and which the Greeks, as stated above, called σκιμαλίζειν. The form of showing contempt which was called the fig is still well known among the lower classes of society in England, and it is preserved in most of the countries of Western Europe. In Baretti’s Spanish Dictionary, which belongs to the commencement of the present century, we find the word higa interpreted as “A manner of scoffing at people, which consists in showing the thumb between the first and second finger, closing the first, and pointing at the person to whom we want to give this hateful mark of contempt.” Baretti also gives as still in use the original meaning of the word, “Higa, a little hand made of jet, which they hang about children to keep them from evil eyes; a superstitious custom.” The use of this amulet is still common in Italy, and especially in Naples and Sicily; it has an advantage over the mere form of the phallus, that when the artificial fica is not present, an individual, who finds or believes himself in sudden danger, can make the amulet with his own fingers. So profound is the belief of its efficacy in Italy, that it is commonly believed and reported there that, at the battle of Solferino, the king of Italy held his hand in his pocket with this arrangement of the fingers as a protection against the shots of the enemy.

Sexual Demons

There were personages connected with the worship of Priapus who appear to have been common to the Romans under and before the empire, and to the foreign races who settled upon its ruins. The Teutonic race believed in a spiritual being who inhabited the woods, and who was called in old German scrat. His character was more general than that of a mere habitant of the woods, for it answered to the English hobgoblin, or to the Irish cluricaune. The scrat was the spirit of the woods, under which character he was sometimes called a waltscrat, and of the fields, and also of the household, the domestic spirit, the ghost haunting the house.

PLATE XI

LEADEN ORNAMENTS FROM THE SEINE

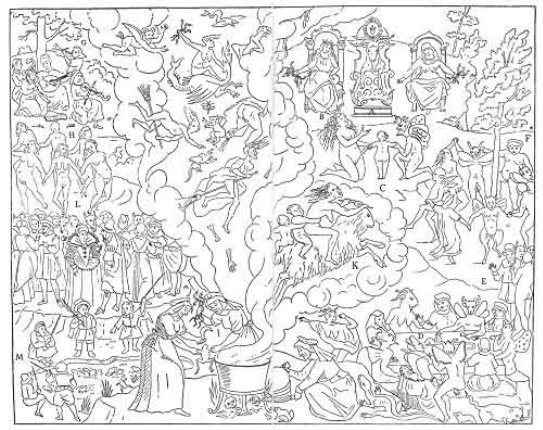

His image was probably looked upon as an amulet, a protection to the house, as an old German vocabulary of the year 1482, explains schrætlin, little scrats, by the Latin word penates. The lascivious character of this spirit, if it wanted more direct evidence, is implied by the fact that fcritta, in Anglo-Saxon, and scrat, in old English, meant a hermaphrodite. Accordingly, the mediæval vocabularies explain scrat by Latin equivalents, which all indicate companions or emanations of Priapus, and in fact, Priapus himself. Isidore gives the name of Pilosi, or hairy men, and tells us that they were called in Greek, Panitæ (apparently an error for Ephialtæ), and in Latin, Incubi and Inibi, the latter word derived from the verb inire, and applied to them on account of their intercourse with animals. They were in fact the fauns and satyrs of antiquity, haunted like them the wild woods, and were characterized by the same petulance towards the other sex. Woe to the modesty of maiden or woman who ventured incautiously into their haunts. As Incubi, they visited the house by night, and violated the persons of the females, and some of the most celebrated heroes of early mediæval romances, such as Merlin, were thus the children of incubi. They were known at an early period in Gaul by the name of Dusii, from which, as the church taught that all these mythic personages were devils, we derive our modern word Deuce, used in such phrases as “the Deuce take you!” The term ficarii was also applied to them in mediæval Latin, either from the meaning of the word ficus, mentioned before, or because they were fond of figs. Most of these Latin synonyms are given in the Anglo-Saxon vocabulary of Alfric, and are interpreted as meaning “evil men, spirits of the woods, evil beings.” One of the old commentators on the Scriptures describes these spirits of the woods as “monsters in the semblance of men, whose form begins with the human shape and ends in the extremity of a beast.” They were, in fact, half man, half goat, and were identical with a class of hobgoblins, who at a rather later period were well known in England by the popular name of Robin Goodfellows, whose Priapic character is sufficiently proved by the pictures of them attached to some of our early printed ballads, of which we give facsimiles. The first[25] (Plate XII, fig 5) is a figure of Robin Goodfellow, which forms the illustration to a very popular ballad of the earlier part of the seventeenth century, entitled “The mad merry Pranks of Robin Goodfellow;” he is represented party-coloured, and with the priapic attribute. The next [26] (Plate XII, fig 2) is a second illustration of the same ballad, in which Robin Goodfellow is represented as Priapus, goat-shaped, with his attributes still more strongly pronounced, and surrounded by a circle of his worshippers dancing about him. He appears here in the character assumed by the demon at the sabbath of the witches, of which we shall have to speak a little further on. The Romish Church created great confusion in all these popular superstitions by considering the mythic persons with whom they were connected as so many devils; and one of these Priapic demons is figured in a cut which seems to have been a favorite one, and is often repeated as an illustration of the broadside ballads of the age of James I. and Charles I. [27] (Plate XIII, fig 1) It is Priapus reduced to his lowest step of degradation.

Phallic Festivals

Besides the invocations addressed principally to Priapus, or to the generative powers, the ancients had established great festivals in their honour, which were remarkable for their licentious gaiety, and in which the image of the phallus was carried openly and in triumph. These festivities were especially celebrated among the rural population, and they were held chiefly during the summer months. The preparatory labours of the agriculturist were over, and people had leisure to welcome with joyfulness the activity of nature’s reproductive powers, which was in due time to bring their fruits. Among the most celebrated of these festivals were the Liberalia, which were held on the 17th of March. A monstrous phallus was carried in procession in a car, and its worshippers indulged loudly and openly in obscene songs, conversation, and attitudes, and when it halted, the most respectable of the matrons ceremoniously crowned the head of the phallus with a garland. The Bacchanalia, representing the Dionysia of the Greeks, were celebrated in the latter part of October, when the harvest was completed, and were attended with much the same ceremonies as the Liberalia. The phallus was similarly carried in procession, and crowned, and, as in the Liberalia, the festivities being carried on into the night, as the celebrators became heated with wine, they degenerated into the extreme of licentiousness, in which people indulged without a blush in the most infamous vices. The festival of Venus was celebrated towards the beginning of April, and in it the phallus was again carried in its car, and led in procession by the Roman ladies to the temple of Venus outside the Colline gate, and there presented by them to the sexual parts of the goddess.

PLATE XII

AMULETS OF GOLD AND LEAD

This part of the scene is represented in a well-known intaglio, which has been published in several works on antiquities. At the close of the month last mentioned came the Floralia, which, if possible, excelled all the others in licence. Ausonius, in whose time (the latter half of the fourth century) the Floralia were still in full force, speaks of their lasciviousness-

Nee non lascivi Floralia læta theatri,

Quæ spectare volunt qui voluisse negant.

Ausonii Eclog. de Feriis Romanis.

The loose women of the town and its neighbourhood, called together by the sounding of horns, mixed with the multitude in perfect nakedness, and excited their passions with obscene motions and language, until the festival ended in a scene of mad revelry, in which all restraint was laid aside. Juvenal describes a Roman dame of very depraved manners as-

. . . . Dignissima prorsus

Florali matrona tuba.

Juvenalis Sat. vi, I. 249.

These scenes of unbounded licence and depravity, deeply rooted in people’s minds by long established customs, caused so little public scandal, that it is related of Cato the younger that, when he was present at the celebration of the Floralia, instead of showing any disapproval of them, he retired, that his well-known gravity might be no restraint upon them, because the multitude manifested some hesitation in stripping the women naked in the presence of a man so celebrated for his modesty. The festivals more specially dedicated to Priapus, the Priapeia, were attended with similar ceremonies and similarly licentious orgies. Their forms and characteristics are better known, because they are so frequently represented to us as the subjects of works of Roman art. The Romans had other festivals of similar character, but of less importance, some of which were of a more private character, and some were celebrated in strict privacy. Such were the rites of the Bona Dea, established among the Roman matrons in the time of the republic, the disorders of which are described in such glowing language by the satirist Juvenal, in his enumeration of the vices of the Roman women:--

Nota Bonæ secreta Deæ, quum tibia lumbos

Incitat, et cornu pariter vinoque feruntur

Attonitæ, crinemque rotant, ululantque Priapi

Mænades. O quantus tunc illis mentibus ardor

Concubitus! quæ vox saltante libidine! quantus

Ille meri veteris per crura madentia torrens!

Lenonum ancillas posita Saufeia corona

Provocat, et tollit pendentis præmia coxæ.

Ipsa Medullinæ fluctum crissantis adorat.

Palmam inter dominas virtus natalibus æquat.

Nil ibi per ludum simulabitur: omnia fient

Ad verum, quibus incendi jam frigidus ævo

Laomedontiades et Nestoris hernia possit.

Tunc prurigo moræ impatiens, tunc femina simplex,

Et toto pariter repetitus clamor ab antro:

Jam fas est: admitte viros!--Juvenalis Sat. vi, l. 314.

Among the Teutonic, as well as among most other peoples, similar festivals appear to have been celebrated during the summer months; and, as they arose out of the same feelings, they no doubt presented the same general forms. The principal popular festivals of the summer during the middle ages occurred in the months of April, May, and June, and comprised Easter, May-day, and the feast of the summer solstice. All these appear to have been originally accompanied with the same phallic worship which formed the principal characteristic of the great Roman festivals; and, in fact, these are exactly those popular institutions and traits of popular manners which were most likely to outlive, also without any material change, the overthrow of the Roman empire by the barbarians. Although, at the time when we become intimately acquainted with these festivals, most of the prominent marks of their phallic character had been abandoned and forgotten, yet we meet during the interval with scattered indications which leave no room to doubt of their former existence. It will be interesting to examine into some of these points, and to show the influence they exerted on mediæval society.

The first of the three great festivals just mentioned was purely Anglo-Saxon and Teutonic; but it appears in the first place to have been identified with the Roman Liberalia, and it was further transformed by the Catholic church into one of the great Christian religious feasts. In the primitive Teutonic mythology there was a female deity named, in Old German, Ostara, and, in Anglo-Saxon, Eastre, or Eostre, but all we know of her is the simple statement of our father of history, Bede, that her festival was celebrated by the ancient Saxons in the month of April, from which circumstance, that month was named by the Anglo-Saxons Easter-monath, or Eoster-monath, and that the name of the goddess had been subsequently given to the Paschal time, with which it was identical. The name of this goddess was given to the same month by the old Germans and by the Franks, so that she must have been one of the most highly honoured of the Teutonic deities, and her festival must have been a very important one, and deeply implanted in the popular feelings, or the church would not have sought to identify it with one of the greatest Christian festivals of the year. It is understood that the Romans considered this month as dedicated to Venus, no doubt because it was that in which the productive power of nature began to be visibly developed. When the Pagan festival was adopted by the church, it became a moveable feast instead of being fixed to the month of April. Among other objects offered to the goddess at this time were cakes, made no doubt of fine flour, but of their form we are ignorant. The Christians, when they seized upon the Easter festival, gave them the form of a bun, which, indeed, was at that time the ordinary form of bread; and to protect themselves, and those who eat them, from any enchantment, or other evil influences which might arise from their former heathen character, they marked them with the Christian symbol--the cross. Hence were derived the cakes we still eat at Easter under the name of hot-cross-buns, and the superstitious feelings attached to them, for multitudes of people still believe that if they failed to eat a hot-cross-bun on Good-Friday they would be unlucky all the rest of the year. But there is some reason for believing that, at least in some parts, the Easter-cakes had originally a different form--that of the phallus. Such at least appears to have been the case in France, where the custom still exists. In Saintonge, in the neighbourhood of La Rochelle, small cakes, baked in the form of a phallus, are made as offerings at Easter, and are carried and presented from house to house; and we have been informed that similar practices exist in some other places. When Dulaure wrote, the festival of Palm Sunday, in the town of Saintes, was called the fête des pinnes, pinne being a popular and vulgar word for the membrum virile. At this fête the women and children carried in the procession, at the end of their palm branches, a phallus made of bread, which they called undisguisedly a pinne, and which, having been blest by the priest, the women carefully preserved during the following year as an amulet.

PLATE XIII

ROBIN GOODFELLOW AND PHALLIC ORNAMENTS

A similar practice existed at St. Jean-d’Angély, where small cakes, made in the form of the phallus, and named fateux, were carried in the procession of the Fête-Dieu, or Corpus Christi. [28] Shortly before the time when Dulaure wrote, this practice was suppressed by a new sous-préfet, M. Maillard. The custom of making cakes in the form of the sexual members, male and female, dates from a remote antiquity and was common among the Romans. Martial made a phallus of bread (Priapus siligineus) the subject of an epigram of two lines:--

Si vis esse satur, nostrum potes esse priapum:

Ipse licet rodas inguina, purus eris.

Martial, lib. xiv, ep. 69.

The same writer speaks of the image of a female organ made of the same material in another of his epigrams, to explain which, it is only necessary to state that these images were composed of the finest wheaten flour (siligo):--

Pauper amicitiæ cum sis, Lupe, non es amicæ;

Et queritur de te mentula sola nihil.

Illa siligineis pinguescit adultera cunnis;

Convivam pascit nigra farina tuum.

Martial, lib. ix, ep. 3.

This custom appears to have been preserved from the Romans through the middle ages, and may be traced distinctly as far back as the fourteenth or fifteenth century. We are informed that in some of the earlier inedited French books on cookery, receipts are given for making cakes in these obscene forms, which are named without any concealment; and the writer on this subject, who wrote in the sixteenth century, Johannes Bruerinus Campegius, describing the different forms in which cakes were then made, enumerates those of the secret members of both sexes, a proof, he says of “the degeneracy of manners, when Christians themselves can delight in obscenities and immodest things even among their articles of food.” He adds that some of these were commonly spoken of by a gross name, des cons sucrés. When Dulaure wrote, that is just forty years ago, cakes of these forms continued to be made in various parts of France, and he informs us that those representing the male organ were made in the Lower Limousin, and especially at Brives, while similar images of the female organ were made at Clermont in Auvergne, and in other places. They were popularly called miches. [29]

There is another custom attached to Easter, which has probably some relation to the worship of which we are treating, and which seems once to have prevailed throughout England, though we believe it is now confined to Shropshire and Cheshire. In the former county it is called heaving, in the latter lifting. On Easter Monday the men go about with chairs, seize the women they meet, and, placing them in the chairs, raise them up, turn them round two or three times, and then claim the right of kissing them. On Easter Tuesday, the same thing is done by the women to the men. This, of course, is only practiced now among the lower classes, except sometimes as a frolic among intimate friends. The chair appears to have been a comparatively modern addition, since such articles have become more abundant. In the last century four or five of the one sex took the victim of the other sex by the arms and legs, and lifted her or him in that manner, and the operation was attended, at all events on the part of the men, with much indecency. The women usually expect a small contribution of money from the men they have lifted. More anciently, in the time of Durandus, that is, in the thirteenth century, a still more singular custom prevailed on these two days. He tells us that in many countries, on the Easter Monday, it was the rule for the wives to beat their husbands, and that on the Tuesday the husbands beat their wives. Brand, in his Popular Antiquities, tells us that in the city of Durham, in his time, it was the custom for the men, on the one day, to take off the women’s shoes, which the latter were obliged to purchase back, and that on the other day the women did the same to the men.

May-Day